Political scientist John Manley dies at 81

John Manley was a dedicated scholar of American government and political and class interest, as well as a committed advocate of academic independence and integrity.

John Manley, professor of political science, emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences, died of Alzheimer’s disease Sept. 5. He was 81.

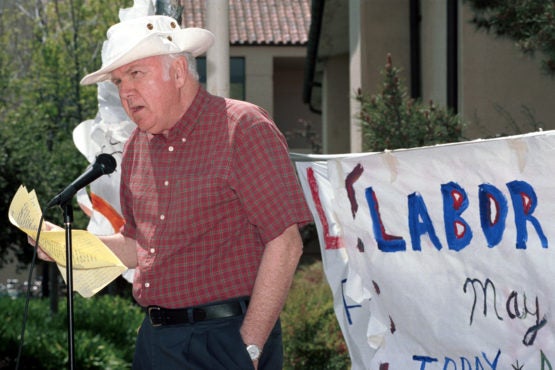

Political science Professor John Manley recounts the history of labor unions at a May Day 2000 event. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Manley, whose 30-year tenure at Stanford began in 1971, was known by his students and colleagues for his strong moral principles, interest in class politics and dedication to social justice causes.

“I will always remember John Manley as a person of great integrity with a huge commitment to social justice issues,” said his friend and colleague Albert Camarillo, the Leon Sloss Jr. Memorial Professor, Emeritus, in the Department of History. “He was one of those few Stanford colleagues who matched his rhetoric on various social and political issues with unbridled activism. John Manley never gave up on a righteous cause.”

As a political scientist, Manley’s scholarship focused on presidential power, public policy making and the function of Congress. He was particularly interested in class politics, political power and influence in American governance.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Manley published papers and books on diverse topics ranging from congressional operations and conflict to presidential power and White House lobbying. In 1972, he published The Politics of Finance: The House Committee on Ways and Means, a deep dive into how the chief tax-writing committee in the House of Representatives operates. In 1976, he authored American Government and Public Policy.

In 1974, Manley received a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to study the conservative coalition in Congress from 1933 to 1972, and he was a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) from 1976 to 1977. He went on to chair the Department of Political Science from 1977 to 1980.

Later in his academic career, Manley turned his attention to analyzing pluralism, a social science theory that argues the United States is a democratic society because political power is dispersed among competing interest groups. Manley brought a Marxist perspective into his critique, arguing that pluralism was incomplete because it failed to account for political and economic inequality and the class structures created by capitalism.

In 1987, Manley co-edited The Case Against the Constitution (From the Antifederalists to the Present), a compilation of 1,500 quotes from 1,000 Supreme Court decisions that illustrate the establishment of American democracy and its values, including due process, free speech, equal rights and freedom of religion.

Five years later, Manley received a Fulbright Scholar award to teach courses on American politics and the American dream at the University of Bologna, Italy.

Committed to economic justice, academic independence

Class politics and economic injustice also motivated Manley’s commitment to activism, including advocating on behalf of low-wage workers in the local community.

“He would often quote Karl Marx and say, with a knowing gleam in his eyes, ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it,’” said his son and Stanford alum Cole Manley, BA ’15. “John Manley changed the world, for the better, in so many ways.”

In 1990, Manley successfully led an awareness campaign on campus with the late English Professor Ronald Rebholz on behalf of employees at Webb Ranch, an independently owned farm that leases land in Portola Valley from Stanford, after it emerged that some families were living in poverty and substandard housing. Their advocacy efforts, which included a rally in White Plaza and an approved resolution put forward by Manley to the Faculty Senate to investigate workers’ living conditions, ultimately led to a settlement that included housing improvements and higher wages for workers.

Manley also cared deeply about protecting Stanford’s reputation as a place for political neutrality. He was concerned about risks to academic freedom being compromised, particularly by political affiliations and financial support from partisan sources – from both the liberal and conservative sides of the political spectrum.

In the 1980s, Manley and Rebholz led several petitions to examine the relationship between Stanford and the Hoover Institution and its independent standing at the university.

When Rebholz died in 2013, Manley offered this advice in his eulogy: “To students: Telling the truth does not mean the truth will prevail, for the power in power is formidable. Most important: Don’t give up.”

Personal life and early career

John Frederick Manley was born Feb. 20, 1939, in Utica, New York. He earned his BS and MA degrees in 1961 and 1963, respectively, from Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York, and he received his PhD in 1966 from Syracuse University. Before joining Stanford, Manley taught for five years at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In 1963-64 he was a Congressional Fellow at the American Political Science Association, participating in a nonpartisan program that brings together political scientists and other professionals to Capitol Hill to learn more about how Congress works through placements as full-time legislative aides in the House of Representatives or Senate.

“Beyond his teaching, he was a lover of many places, many people and many things,” Cole Manley said. Some of those passions included reading, writing and traveling, and sometimes all three.

“He often mused about buying an apartment in North Beach, San Francisco, so he could be near one of his favorite bookstores, City Lights. In Paris, meanwhile, he wanted a pied-à-terre near Notre Dame and the Shakespeare & Co. bookstore. Paris was, after New York, his favorite city.”

Manley is survived by his wife, Kathy Sharp ( BA ’80, JD/MBA ’85), and three children, John, Laura and Cole.

There will be arrangements for a memorial service at Stanford at a later date.