High-tech imaging center opens at Hopkins Marine Station

The newly renovated space with confocal microscopes offers Stanford researchers the rare opportunity to study the cellular and molecular structures of marine organisms that hold clues to the evolution of life, right on the shores of the ocean where it all started.

Life began and diversified in the ocean, and now Stanford is providing a new, easier way for scientists to get a good look at it.

The Molecular and Cellular Biodiversity Imaging Center, the brainchild of Christoper Lowe, biology professor in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S), is now open at Hopkins Marine Station. It allows researchers from a range of disciplines access to technology rarely found at a marine station, including two brand-new confocal microscopes, which produce images of organisms at cellular and molecular levels. There is also a dedicated makerspace for researchers to build novel technologies and apply them to new species. These resources are all just steps from Monterey Bay at the station, which is part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

The imaging center offers researchers improved ability to study marine organisms with unusual and potentially useful features such as sea stars that can regenerate limbs, ocean tunicates that form a new brain every week, and corals that live for thousands of years. Species like these present great opportunities for biological discovery with implications for human health as well as survival of animals in a changing climate, Lowe said.

“If you want to understand the fundamentals of how life evolved on the planet and how animals solved basic biological problems, then the ocean is the natural place to go and start to figure that out,” he said.

The imaging center was created through the renovation of about 700 square feet of existing space on the Hopkins campus through collaborative funding from the School of Humanities and Sciences and the Doerr School of Sustainability.

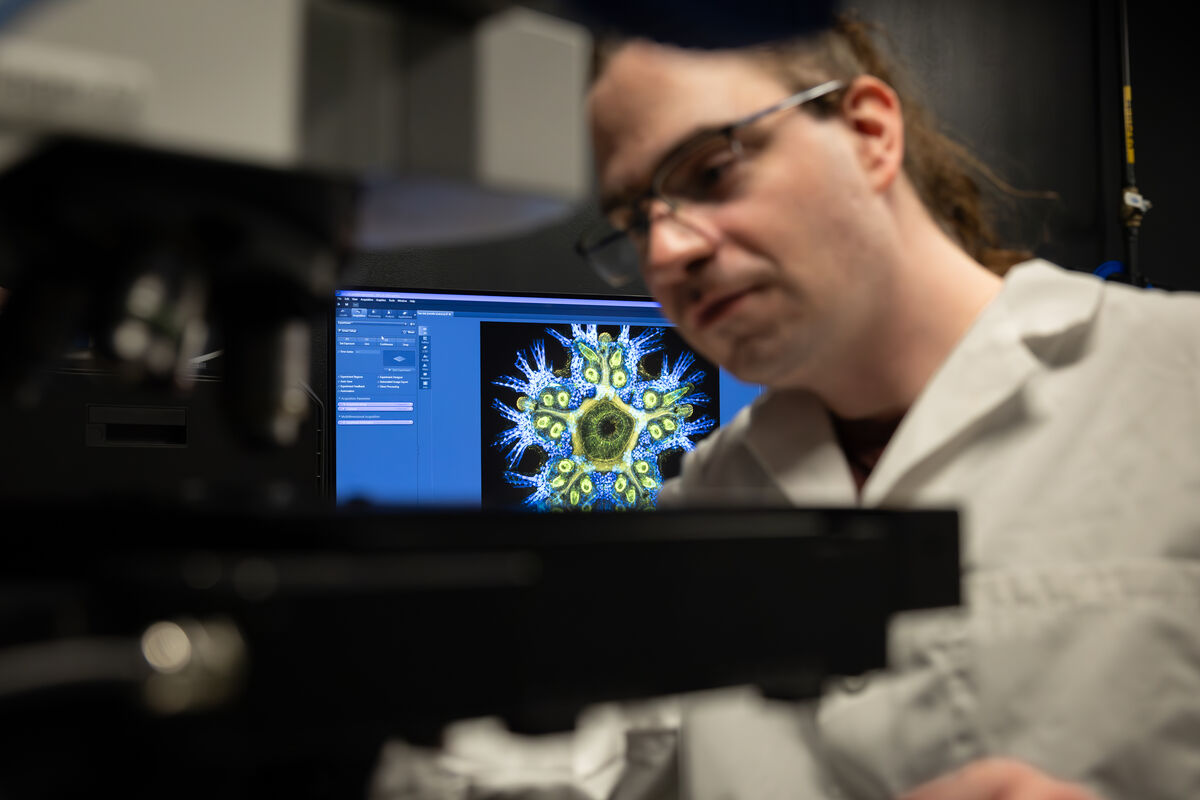

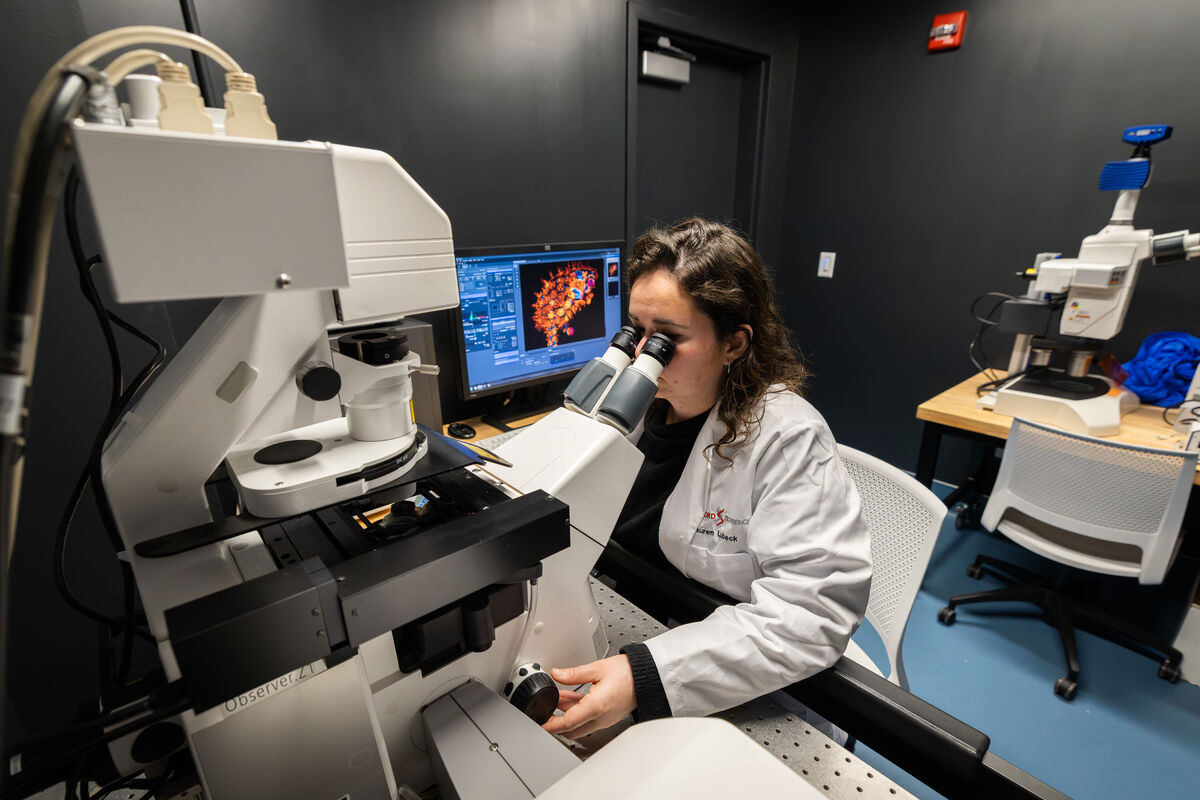

The center features a common area for meetings and another area with a set of traditional stereo microscopes that allows scientists to view whole animals and prepare samples to be taken into temperature-controlled, dark rooms for more detailed imaging. Two of these rooms contain confocal laser scanning microscopes, including the Zeiss LSM 900 and 980. These microscopes can perform imaging at very high resolutions with low levels of light, as strong light can harm living marine organisms. They also allow different scales of imaging, from viewing the entire animal, to seeing inside cells, to focusing on individual proteins moving around inside cells.

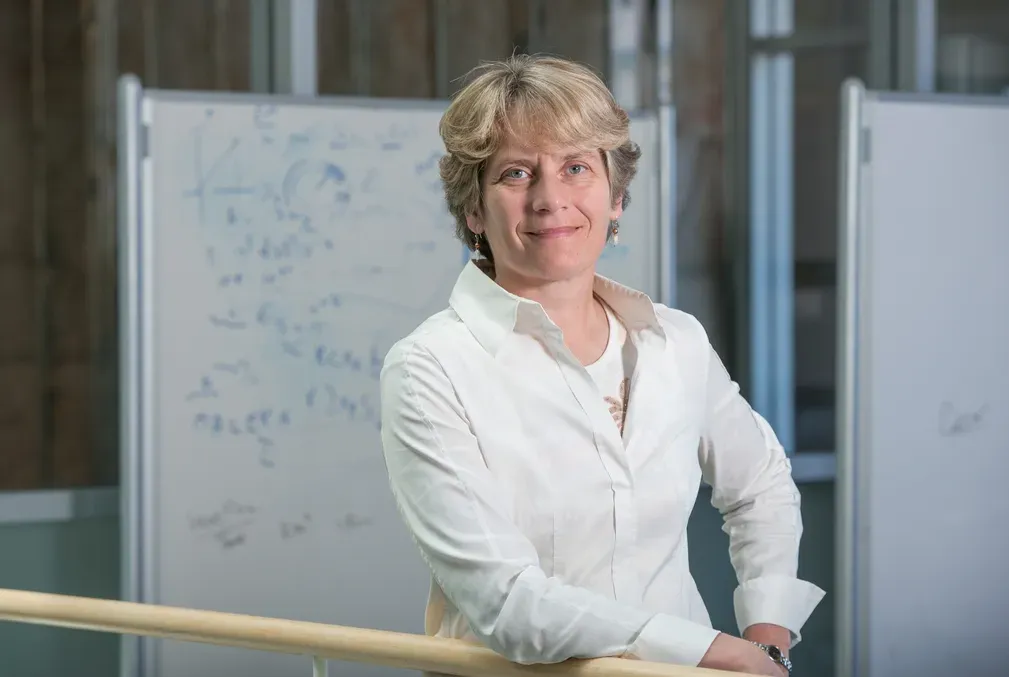

“There are very few marine stations in the world that have this kind of equipment on hand,” said Vanessa Barone, assistant professor of biology in H&S, who has a lab at Hopkins. “My hope is that this will help enable the station to become a hub for people to come from institutions all over the world to run experiments and projects.”

Although the center is part of the H&S Department of Biology, it is intended for researchers from a variety of fields, including those already represented at Hopkins as well as others in Stanford’s Schools of Engineering and Medicine.

A third room in the new space is specifically designed to accommodate visiting scientists interested in developing new research technologies. This kind of work was being done at Hopkins before the center was built. For example, Stanford bioengineer Manu Prakash developed the "planktoscope" and the “gravity machine.” These instruments allow researchers to image and observe planktonic life forms such as larvae as they naturally move and float in a column of water as opposed to rendering them motionless to fit under a viewing lens. These tools have now reached all corners of the world, including the Arctic and Antarctica.

Lowe and Barone hope that having the new space will lead to more innovations like this since there will be space set aside for development, particularly for equipment that needs a light- and temperature-controlled environment. Already, a researcher from the University of California, Santa Barbara is scheduled to visit to develop a light sheet microscope on site.

Foundational research on the numerous and diverse marine organisms able to be studied at Hopkins Marine Station has the potential to yield advances in a range of fields, Lowe said. He pointed out that investigation into jellyfish at a marine station led to the development of green fluorescent protein, also known as GFP, which is now used widely in biomedical and neurobiology research.

The biologists are also trying to develop new genetic tools so that some marine organisms such as sea stars and sea urchins can be used as model research species, much the way fruit flies and mice are used in laboratories today.

Realizing these goals requires careful handling of often-fragile marine organisms that depend on seawater to survive. To this end, many Hopkins labs have filtered seawater on tap—it is piped in and available at the turn of a spigot.

Conducting cellular and molecular imaging of these animals near where they are found is also helpful. Before the imaging center opened, researchers had to pack up the marine organisms for a two-hour drive to the Stanford campus to access confocal microscopes. Now that same technology is available just a short walk from the shoreline.

“We are a portal to the extraordinary biodiversity that’s hard to access except through a marine station,” Lowe said. “We are open for business, and we’re looking forward to people reaching out with interesting ideas of projects that we can help facilitate.”

Acknowledgments

Lowe and Barone are also members of Stanford Bio-X, and Lowe is a member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Prakash is an associate professor of bioengineering in the School of Engineering and a senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment.

Media contact: Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)