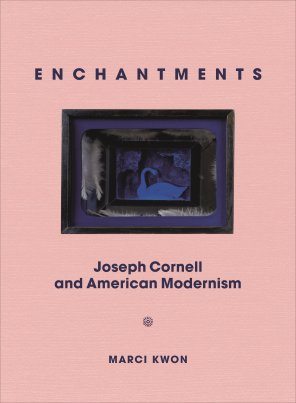

New book examines work of artist Joseph Cornell

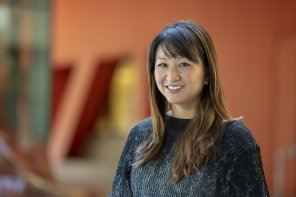

Stanford art historian Marci Kwon examines the work and life of the midcentury artist through the lens of enchantments.

In her new book, Enchantments: Joseph Cornell and American Modernism (Princeton University Press, 2021), art historian Marci Kwon uses the notion of “enchantment” as a starting point to delve into deeper questions about the artist’s life and the lasting impact of his ethereal, yet grounded work.

“I love that, like me, Cornell loves birds, ballet, bubbles, and movie stars,” said Kwon, assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “But when I look at his art, I also see ambivalence, melancholy, and fear beneath its veneer of lightness. I feel an unresolved tension between faith and doubt. In this book, I’m interested in how Cornell was both in and out of step with modernity. Following his work and reception across four decades, I show how enchantment formed a crucial if underrecognized strand of American modernism.”

Perhaps best known for his wooden boxes—often referred to as “shadow boxes”—that housed small items he had carefully assembled, Cornell was a contemporary and collaborator of preeminent 20th-century artists, poets, and filmmakers like Robert Motherwell, Mina Loy, and Stan Brakhage. Kwon was first introduced to Cornell’s work when she was a sophomore in college and saw his work displayed in the Surrealist gallery at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

One of those was Taglioni’s Jewel Casket from 1940, which contains glass cubes that mimic diamonds. “Just twelve inches wide, this modest box holds a world,” Kwon writes, taking pleasure in the magic of Cornell’s creation.

“Unlike the painters and sculptors who preceded him in MoMA’s galleries, Cornell eschewed the hallowed mediums of paint, marble, and bronze in favor of altogether more modest materials,” Kwon writes. The artist used a broad range of found objects—a fragment of driftwood or a photograph—to create in various media including collage, film, and graphic design layouts for popular publications such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

Unveiling enchantment

Kwon examines the artist through the lens of enchantment or the experience of something that exceeds rational comprehension. The concept is often associated with the divine, but it can also refer to the metaphysical, the ideal, the occult, or the sublime effects of poetry or art, she said.

There’s also a historical component to the concept of enchantment, because what is considered “rational” changes depending on the cultural context of the era. “For instance, German sociologist Max Weber used the phrase ‘disenchantment of the world’ (die Entzauberung der Welt) to describe modernity,” Kwon said. “This influential idea positioned enchantment as antithetical to modernity, and it made synonymous modernity and rational thought.”

But Cornell’s life and art challenged that construct. “What makes his work so compelling is this juxtaposition of the earthly and the transcendent—of the world’s lightness and its heaviness,” Kwon said.

Modernity and religion

Cornell was a practicing Christian Scientist for most of his life. He believed that the divine is present in the world around us and that the past is not dead and gone but can be felt in the present, Kwon said.

“Such beliefs are incompatible with the view of modernity as disenchanted,” she said. So from this perspective, Cornell can only be understood as “eccentric” or “withdrawn.”

“Why, I wondered, was the price of Cornell’s modernity the abnegation of his most deeply held principles? How did belief become antithetical to intelligence and seriousness?” Kwon writes.

What Kwon found by following the impact of Cornell’s work and the reception it received was a shift in the definitions and attitudes toward enchantment in the mid-20th century. As Kwon writes, “Debates about enchantment and disenchantment were mobilized in period conversations over art’s relationship to the public, to popular culture, and its potential for moral authority. While enchantment (via Symbolism and Surrealism) was understood as a demotic, critical artistic ethos in the 1920s and ’30s, the rise of totalitarianism at midcentury led enchantment to be denigrated as a means of social control and propaganda.”

These shifts affected not just Cornell but a range of artists, filmmakers, and poets, including poets Mina Loy and Marianne Moore. In the book, Kwon discusses three artists from the postwar period who explicitly drew on Cornell’s work: Robert Rauschenberg, Betye Saar, and Carolee Schneemann.

To examine Cornell’s work and life, Kwon drew on numerous archives around the country including the Joseph Cornell Study Center at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The study center holds the contents of his studio upon his death, including a vast library of annotated sources, boxes of materials, research dossiers, and even some incomplete works.

Worlds of humble things

The book also served to help answer an important question that Kwon had been wrestling with: Why are some ways of being in the world taken less seriously than others? “I learned the importance of perseverance—of continuing to make art—even in the face of a world that is determined not to take you seriously,” she said.

Another lesson for the art historian was in Cornell’s ability to conjure worlds from humble things, like making chips of glass look like diamonds. “The smallest things are often the most consequential,” Kwon writes. “Perhaps enchantment is not some lost cosmic unity, some long-departed force, but simply a recognition of that which has been with us all along.”

Kwon is speaking about her book at a virtual event hosted by the Stanford Humanities Center on Wednesday, March 31 at 11 a.m. Registration for the event is required.