New book explores historical fiction’s role in the rise of Japanese nationalism before World War II

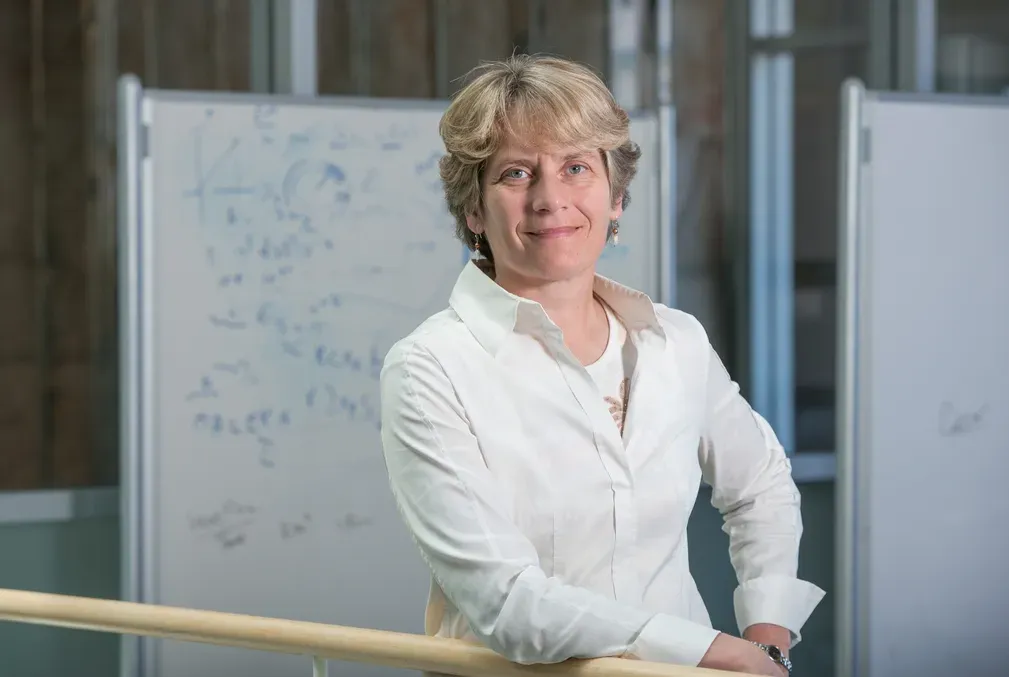

Literature for the Masses, by East Asian Studies scholar James Reichert, draws comparisons between that era and ours.

It might be a cliché to say the samurai plays a similar role within the Japanese popular imagination as the cowboy does in America, but that doesn’t make it any less true. And just as writers like Louis L’Amour were writing Western novels that prized action and romance over historical accuracy, Japanese writers of the early 20th century were doing the same for the samurai.

That literature, and the circumstances that gave rise to it, are the subject of Literature for the Masses: Japanese Period Fiction, 1913-1941 (University of Hawaii Press, 2025), a new book from James Reichert, associate professor of East Asian languages and cultures in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences. In it, he explores how samurai adventure stories became popular in Japan in the years before World War II and entrenched a myth of noble battle and traditional masculinity that helped pave the way for that country’s nationalist movement, resulting in its disastrous defeat in 1945.

The book grew out of Reichert’s lifelong fascination with Japan and the mythological stories its authors have told about the country over the centuries. The book feels especially relevant at the moment, for reasons both good — the FX series Shogun is an award-winning retelling of the stories covered in Reichert’s book — and ominous, with nationalism on the rise both domestically and abroad.

Here, Reichert discusses those connections, including how Japanese popular culture from a hundred years ago resembles that of the 21st century.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: What went into writing and publishing this book?

Answer: I was looking for a new project, and I'd always been interested in historical fiction. Very few people have written about it, even though it's just absolutely ubiquitous in Japan. Even today, there are historical fiction dramas on TV, and films and comic books and animation and video games.

It took me a while to fit all the pieces together. The text that kind of made it all click for me is actually Gone with the Wind— I was interested in the fact that the two most successful pieces of fiction published in the 20th century in Japan are Miyamoto Musashi [by Yoshikawa Eiji], which is a very famous example of this genre of historical fiction. The other one is Gone with the Wind. It really had a big burst of popularity after the war, as Japan was dealing with occupation.

Question: Did anything else inspire the book?

Answer: As I was working on it, all this other political stuff was happening in the United States, and I think that was always kind of in the back of my mind as I was thinking about the project. This idea of action over thought, feelings over facts, making up history as you see fit — just appealing to people with lots of drama, lots of action, lots of shocks — seemed like they were very similar to Make America Great Again.

Question: Well, certainly rising nationalism is a hot topic in the U.S. right now. What can we learn from your book?

Answer: What my book delves into is that the producers of these Japanese books found this untapped market of readers. They provided people with material that they liked, and in doing that, they established a way for the readers to feel connected in this larger project. There was a sense of connection to history, even though that history was sort of flagrantly inaccurate.

This genre created an opening for people to form a really strong emotional connection to a fantasy version of what Japanese history was. All these experts were poo-pooing the material and saying, “Well, you shouldn't read it. It's not accurate; only stupid people would be persuaded by any of this.” But the fact that the elites and the experts didn't like it made it more popular. I feel like there is a real, clear parallel to what is happening now.

So what could it teach us? I guess one thing is that just dismissing people for being moved by MAGA material is probably the wrong way to go about it. Instead, maybe figure out what's moving to them about it.

The Japanese material was very organic. It didn't seem forced. It respected the audience, respected what they wanted, and didn't tell them that they were wrong to like it.

Question: How did you become interested in Japan in general?

Answer: When I was a little kid, I was really into Godzilla movies. They were on TV something like five times a year. I thought they were so cool, and that piqued an interest in Japan for me.

I graduated from college in 1984, when Japan was booming, and I got a job teaching English there. I loved it. I felt really comfortable in a way that I didn't expect to. Eventually, I went back to Japan to do research at the University of Tokyo as a graduate student, and I was there for three years again.

Question: The FX series Shogun is based on a popular book from the ’70s, which was first adapted into a 1980 miniseries. How does it relate to your book?

Answer: One of the points I make in my book is that there's this stuff called period fiction, which just uses history as a pretext to do all of this adventure and excitement, and the authors just reinvent history willy-nilly. And then there's another form that's called the historical novel, which really tries to be historically accurate.

The book’s author, James Clavell, who’s not Japanese, really leaned into the period fiction tradition. There's a lot of adventure; there's a lot of sex. The novel centers an English guy who goes to Japan. I think the reason why it was such a big hit in the United States [as both a novel and miniseries] is that what's happening in Japan is this thrilling backdrop, but the main focus is on the growth of the English character and how he internalizes some Japanese values but resists other ones.

The new TV version is closer to a historical novel. The producers are trying to be really accurate, and there is a real effort to keep the Japanese characters front and center. For example, when the English protagonist is not around, the Japanese characters speak a variation of classical Japanese, which all of the actors talked about how hard it was to learn. Part of the pleasure, or part of the value, of the series is how much research everyone involved with Shogun did, how much work they put into figuring out the way that characters in this environment would speak.