Body images: How tech can co-opt our physical selves—and how art can save us

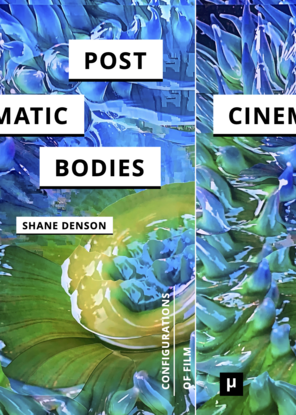

A new book by Shane Denson explores the intersections of biodata and media art and how predictive algorithms are reshaping perceptions of the human body.

Shane Denson is an associate professor of film and media studies at the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences. He’s also a deep thinker about our data-rich world and the technologies driving it. Biosensing technologies, such as virtual reality, wearable trackers, and smartwatches, both harvest and commoditize physical data that come back to us as advertisements and lifestyle recommendations. In his latest book, Post-Cinematic Bodies (Meson Press, 2023), Denson charts a troubling encroachment on the human body—a phenomenon he calls “metabolic capitalism,” which applies dangerous norms of age, beauty, gender, and race to alter how we perceive our bodies. We talked to Denson about his viewpoint and why he thinks there is still hope for change.

Question: What is your basic argument?

Denson: Post-Cinematic Bodies argues that the contemporary media landscape—characterized by predictive algorithms, “smart” devices, robots, and so on—subtly transforms our bodies and our embodied relations to the environment. For example, smart devices track our every movement and measure each calorie, turning our metabolisms into data that is bought and sold. These devices are mediating a new system of “metabolic capitalism.” We are being subtly “alienated” from our own bodies as our physical habits are enlisted in producing revenue for corporations.

Question: You say this is a matter of aesthetics, but also of politics. In what ways is it political?

Denson: The goal of the book is twofold: first, to shed light on the way that our bodies are integrated and anticipated by these systems—often without our awareness; and second, to imagine ways contemporary media art can help us resist co-optation. In political terms, if virtual reality, augmented reality, wearables, and other forms of new media were ever to fully enlist our bodies as producers of value, our behaviors would have to be made predictable. Thus, our bodies are being “normed” by facial recognition, augmented and virtual reality, and generative AI. This norming process has far-reaching implications for constructions of gender, ability and disability, race, and other deeply political matters.

Question: You say technologies are “challenging the existential relation that ‘I’ have to ‘my’ body.” Is human existence under threat?

Denson: I don’t know that I would go so far as to say that human existence is under threat, at least not in the science-fictional imagination of AI taking over. The threat is far more mundane but insidious nonetheless. The new algorithmic media, operating predictively and at microtemporal speeds, bypass our consciousness to take aim at bodily processes—metabolism, heart rate, eye movement, brain wave activity—exposing them to predictive shaping. I am most worried about the way algorithms standardize perception and action, threatening human diversity. If, as the existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre asserted, “existence precedes essence” and each of us is free to forge our own essence, then these new technologies are preempting our decision-making agencies. New “essences” might be engineered and implemented algorithmically, before we can even blink, much less think. These systems are apparent in something as routine as a Snapchat selfie where we perceive ourselves in a virtual mirror augmented with bunny ears or a big mustache. Each Snapchat filter is founded on norms of what a “typical” face looks like and also applies troubling normative schemas of age, weight, race, and beauty. The algorithms are an intervention between self and perception. Ableist, racist, and gender-essentialist biases become the real-time filter through which the embodied subject (mis)recognizes itself.

Question: The endgame here appears grim. Is it?

Denson: I’m not often accused of being an optimist, but I’m not a pessimist either. Throughout the book (and my previous book, Discorrelated Images, Duke University Press 2020), I am at pains to show the cracks in the façade offering opportunities to redirect technology toward better ends—or to build a less awful world, at least. A lot of what makes these systems so cynical is the consolidation of power. The data is generally invisible to the users who produce it and who are in turn influenced by it. Worse yet, the markets where the data are traded are invisible, too. Maybe this only shapes the ads I see, but what happens when my insurance company has the data?

Question: Are there remedies?

Denson: Occasionally, metabolic capitalism becomes visible; most often it’s through art. The artists I highlight in the book—Ian Cheng, Hito Steyerl, Hyphen-Labs, Catie Cuan, Rashaad Newsome, Teoma Jackson Naccarato and John MacCallum, and Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, among others—are transforming these invisible algorithms into sensory experiences. Some are interested in reengineering the bodily norms to challenge the white, heterosexist norms at the heart of the algorithms. They are doing things like building motion-capture libraries focused on African and African American dance. Others provide embodied experiences of metabolic capture by turning them into aesthetic events. It is the artists who give me hope. They show that it is still possible to rearrange the relationship between users, infrastructures, and experiences—if only we can redistribute or challenge the underlying power structures.