Foundational research on brain development may help prevent degeneration

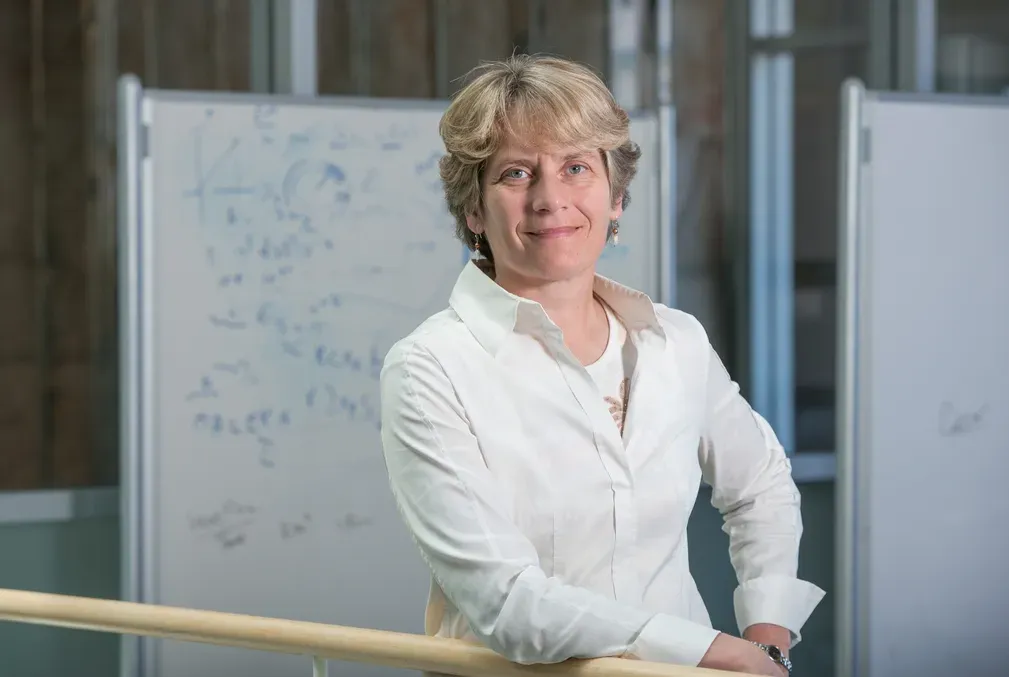

Stanford neurobiologist Carla Shatz, famous for discovering how neural connections develop early in life, is using that knowledge to work on the problem of how they can later deteriorate from Alzheimer’s disease.

It all started with a question. When Carla Shatz began her lab at Stanford, she wanted to know how the eye initially connects with the brain to receive visual information. It was foundational research: There was no specific problem she wanted to solve or disease treatment to test, but what she found dramatically changed how researchers understood brain development.

Shatz’s team discovered that the brain’s ability to process vision doesn’t come completely hardwired, as was previously believed. The basic framework of neural connections, called synapses, is formed early, but in a later phase, activity shapes the process. The synapses that are used are strengthened, while those that are unnecessary are cut. This sculpting, or “pruning and tuning,” of synapses was later found to be happening not just for vision but in all kinds of brain development.

In recent years, Shatz, a professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences, has been using that knowledge to help combat Alzheimer’s disease. She hypothesizes that the condition might be the result of the synapse pruning process going into overdrive.

“In my lab, we traveled from fundamental, curiosity-based voyages of discovery to those relevant to the human condition and disease,” said Shatz, who is also a neurobiology professor in the School of Medicine. “We went from neural development on the one hand to neural degeneration on the other—from the developmental sculpting of synapses to the tragic sculpting of synapses that store memories as happens with Alzheimer's disease.”

Working with a model of Alzheimer’s disease in mice, Shatz and her colleagues knocked out molecules necessary for the pruning of synapses. Reporting in the journal Science in 2013, the team showed that the mice without those molecules did not develop the memory loss associated with the disease.

The researchers are now conducting the painstaking work necessary to learn more about these molecules and mechanisms so that, ultimately, a new drug could be designed to block the overpruning of synapses and prevent memory loss in Alzheimer’s.

Many more steps are needed before getting to that point, but this approach holds new hope for addressing a disease that has no cure. Shatz said that clinical trials for new Alzheimer’s drugs have so far been “very disappointing.” Part of the problem, she believes, is that many assumptions about the disease are not based on fundamental science.

“Many researchers are starting with the dysfunction when it’s present—whether it’s in autism or Alzheimer’s—and the dysfunction frequently happens months to years after the original problem arises in the brain,” she said. “There might be mechanisms that go awry early in development, even in utero, that have to do with rehearsing or training these neural circuits.”

Foundational science matters

In many ways, Shatz’s entire career is a testament to the value of fundamental research, also referred to as discovery science, basic science, or curiosity-driven research.

Shatz followed her curiosity as a student who was fascinated by both art and science into neuroscience, a very new field at the time. For her doctorate at Harvard, she studied under David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel whose work on how the brain processes visual information later won them the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Her mentors always described their work as a voyage of discovery, a metaphor she has taken to heart.

“It's a wonderful way of thinking about basic research,” she said of the mindset of her former advisers. “You have a ship, you have tools, and you set out. You don’t really know what you're going to discover—the voyage itself reveals the knowledge. It's pretty amazing.”

When Shatz began her Stanford voyage in 1978, she received funding for a foundational research project from the National Institutes of Health simply to study how the eye connects to the brain. At the time, her proposal did not have to directly address a specific disease. She went on to receive additional grants from the National Eye Institute and others.

“Because I got that first NIH grant, it launched my career,” she said. “I got tenure and published papers, and we made some extremely important discoveries.”

Shatz worries that early-career researchers will not have the same ability with the loss of support for foundational research—a problem that started even before current proposals to drastically cut NIH funding. She always advises junior faculty to have two research projects when they start their labs, one a high-risk dream project and another focused on a disease that is more likely to get NIH funding.

But even in these challenging times, Shatz remains hopeful and urges her colleagues not to abandon foundational science.

“Somehow we will come back, and I really do not want our students and junior faculty colleagues to ever give up on their visions and their big questions, which are frequently fundamental questions,” she said. “Because that’s where the major discoveries and breakthroughs are made.”

Shatz is also the Sapp Family Provostial Professor and a member of Stanford Bio-X, which she directed for 17 years. In addition, she is a faculty fellow at Sarafan ChEM-H as well as a member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

Media contact:

Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, 510-872-0340, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)