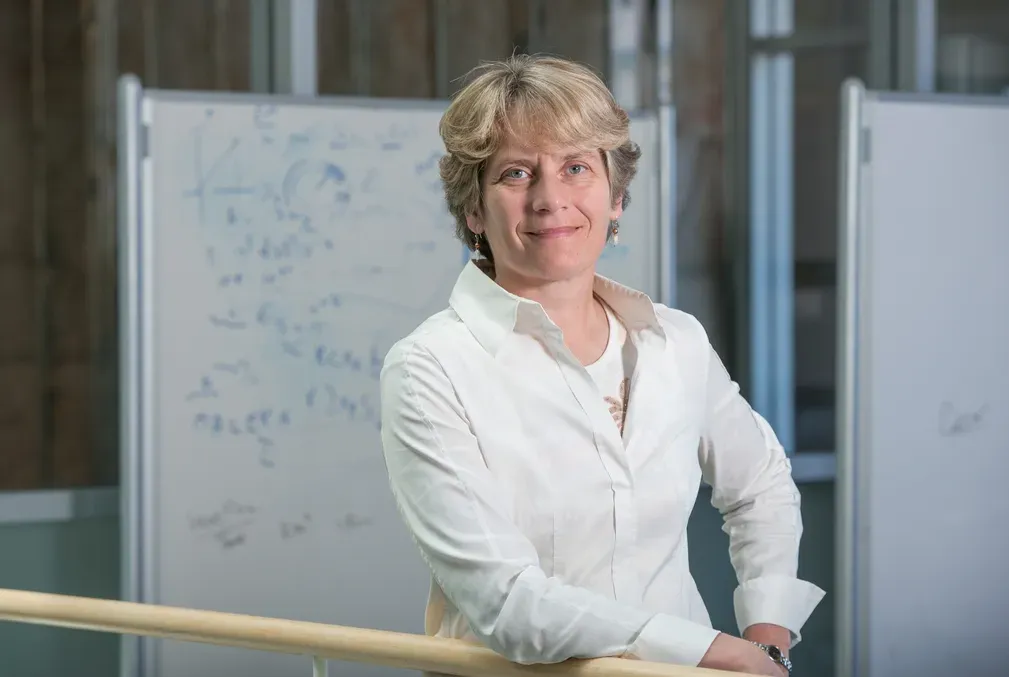

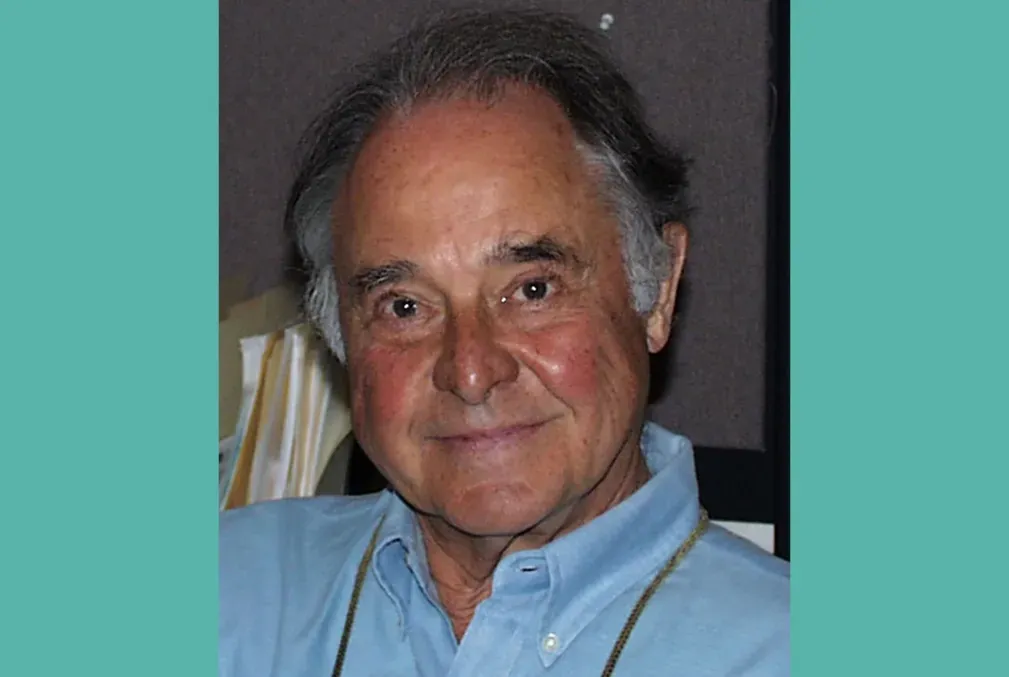

Historian Gordon H. Chang reflects on his varied career with new book

In War, Race, and Culture, a book of collected essays, Chang documents a lifetime of scholarship and activism.

Not many people could tell their life story and reduce the time they got stabbed to a single sentence. But such is the life of Gordon H. Chang, the Olive H. Palmer Professor in Humanities and professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences, who chronicles his upbringing and his career as an academic and activist in the introduction to his new book, War, Race, and Culture: Journeys in Trans-Pacific and Asian American Histories (Stanford University Press).

The book is a collection of his essays, published over the course of Chang’s three-and-a-half-decade career. He opens it with an “intellectual memoir” to make the point that he has always engaged with history from a personal perspective, and this has driven his academic pursuits. The introduction covers his experiences as a Chinese American, his many years as a political activist (including the aforementioned stabbing: “I was knifed in the back over politics by rightist New York Chinatown street gang members and sent to the hospital.”), the right-wing response to his appointment at Stanford in 1990, and more. It prepares the reader for what follows: essays on such wide-ranging topics as the racial attitudes of U.S. presidents, the role of art in U.S.–China diplomacy, and a World War II-era Superman comic.

Here, Chang, who is also a co-founder of the Asian American Research Center at Stanford and its inaugural director, talks about what he learned from this project and how his experiences with racism and political activism prepared him for our current moment.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: How did the book come about?

Answer: Last year, I was a resident at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and I had the whole year off to research and write and think. I had been thinking about putting together a collection of my essays, and that afforded me the time.

Question: How does the book’s structure—around the three title themes—reflect your career?

Answer: At the start, I was very much focused on international relations and high-level geopolitical thinking. I also always had a personal interest in Asian American history because of my ancestry.

Later, when I ventured off into serious scholarship on Asian American history, some colleagues wondered what I was doing because the work that I pursued did not fit neatly into existing paradigms or even scholarly societies.

The subject areas of war, race, and culture can stand alone and be understood separately. But at the same time, I also see them as interconnected. In my writing about culture, I think about the relationship of art to not only ethnicity and race and lived experience as racial minority artists, but also the circumstances in which the art is created. So much of art has been influenced by war.

Question: In an essay from 1993, you write about a comic that alarmed the Roosevelt administration—Superman visits the incarceration camps during World War II and prevents anti-American sabotage by so-called “disloyal Japanese.” How did you come across that?

Answer: I was at the Truman Presidential Library in Independence, Missouri, working on Cold War history and Truman’s policy toward China during the Chinese civil war. I always had an open eye to look for interesting archival material. And I saw this whole section about Japanese American incarceration during World War II, and that's where I located the files that ultimately make the core of that essay.

If I didn't have that mindset of thinking about race and war, I probably would have just passed over those files.

Question: In the introduction, you write that your Chinese American family felt “vulnerable” at the height of the Cold War. Do you feel any of that vulnerability right now, and has your past shaped your mindset?

Answer: The issue of vulnerability has come up within my family. My two daughters are both in college. My wife and I have been together for three decades now. We're all American born. And we've felt really vulnerable—for politics, for gender reasons, and for race.

It's also come up with thinking about the implications of what was called The China Initiative during the first Trump administration, which sparked federal investigations of many scholars of Chinese ancestry. They suffered an intellectual form of racial profiling.

It's also influenced my continuing scholarship. I'm now studying the career of a Chinese missile scientist, Qian Xuesen, who came to the United States in the 1930s and later helped the U.S. understand the Nazi rocket science program. During the Red Scare, federal authorities targeted him, and he was forced to leave. Back in China, he led their rocket program and became their most famous modern scientist—their Oppenheimer.

Question: Finally, how did Stanford support the book?

Answer: I have sincerely appreciated the support I've received from my colleagues at Stanford in the Department of History and other departments and the administration. The university is a community of eminent scholars who support humanistic values and the pursuit of knowledge. They respected me as a young scholar, as an unusual scholar, and they continue to do so.