New English courses fuse creativity with literary criticism

Students perform Richard III as part of a course in which they deeply studied the play and then acted in it.

The Critical–Creative Studies Initiative offers students the chance to understand literature from multiple angles.

It seems obvious. Critics publish criticism. Creative writers publish creative writing. And therefore, those who aspire to do the former should focus their studies on interpreting and analyzing literature. Those who aspire to the latter should focus on writing poems, plays, novels, short stories, and so on.

But in real life, writers often publish work in both categories. Moreover, even those who focus on one will benefit from the study of the other. And yet the disciplines are often siloed, depriving students of the opportunity to immerse themselves in a work, to understand how a piece functions, and to produce a new piece of their own.

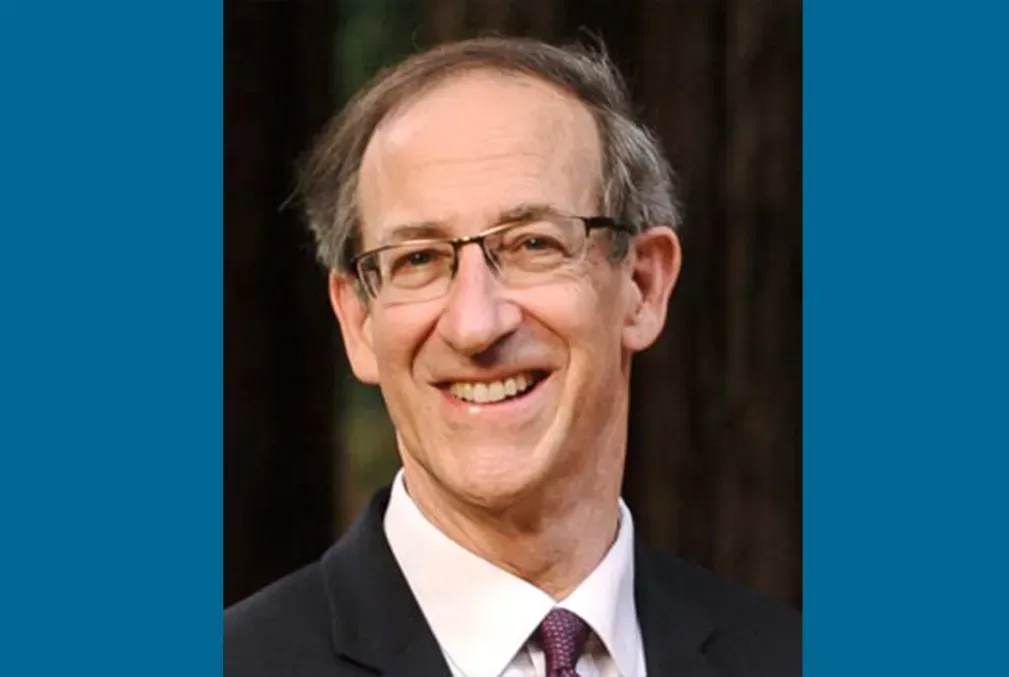

Breaking down those barriers is the impetus behind the Critical-Creative Studies Initiative (CCSI), a new four-year pilot program for undergraduates in the Department of English in the School of Humanities and Sciences. It’s the brainchild of Peggy Phelan, the Ann O’Day Maples Professor of the Arts and the CCSI director, and Gavin Jones, the Frederick P. Rehmus Family Professor of Humanities and chair of the Department of English. They were inspired both by developments in the field—for example, Columbia University professor Saidiya Hartman, who combines critical theory and fictional narrative in her work—and interest from students.

“Students themselves are making these fusions between the critical and the creative,” said Jones, who is also acting director of the Creative Writing Program. “Everything that’s happening in terms of the broader intellectual picture, you can see as a reality on the ground here at Stanford. We want to be leading the way in terms of innovation and experimentation. I think it is the future of the humanities.”

Forging links for students in the social media age

CCSI’s first offerings came in fall quarter, a slate that included such courses as Poetry and Magic, Autofiction: Transforming the Story of the Self, Medieval Ecologies, and one in which the students both studied and performed Shakespeare’s Richard III (more on that in a moment). This quarter, there is a course on autobiographical writing, and in spring quarter, there will be courses on science fiction, sports and climate literature, and one on contemporary American short stories co-taught by Jones and creative writing lecturer Jenn Alandy Trahan.

The idea is to encourage students to use both their creative and critical sensibilities. In addition to scholarly inquiry about the historical, formal, and political arrangements of texts, students are also invited to respond to literature with creative texts that are in dialogue with it. As Phelan noted, it’s something students are already doing on their own, thanks in part to such innovations as social media and smartphones.

“They have really made it possible for everyone to be an artist,” said Phelan, whose interest in this fusion is attributable in part to her background as both a professor of English and a professor of theater and performance studies. “So the typical undergraduate comes to Stanford with a history as a maker. In CCSI courses, we invite students to bring that experience with them as we enlarge their understanding of literary history and the critical responses to it. CCSI is the most explicit way to forge links between scholarly and creative approaches to literary texts. And that’s why I think the appetite for it has been so great.”

‘There was so much joy in that class’

CCSI’s innovations were demonstrated in the fall course Page to Stage: The Case of Shakespeare’s Richard III, taught by Esther Yu, an assistant professor of English. It explored the bard’s chronicle of a power-mad English king and the murderous lengths he goes to in order to claim (and hold) his crown. Students not only studied the play extensively, but also screened past performances from Laurence Olivier, Ian McKellen, and Benedict Cumberbatch, and—most importantly—performed the play themselves, with each student taking a turn in the titular role. (Students also took on additional roles such as adapting the script, publicizing the performance, and designing “R3” baseball caps for onstage wear.)

“Literary criticism, as I understand it, is thoroughly creative,” Yu said. “It does not, as I practice it, turn on some deep division between the analytical and the imaginative. This new initiative understands that. It names a challenge that I feel strongly about taking on: the challenge of persuading students that the pathway to creative expression lies through the probing, prolonged inhabitation of literary realms not necessarily of their own making.”

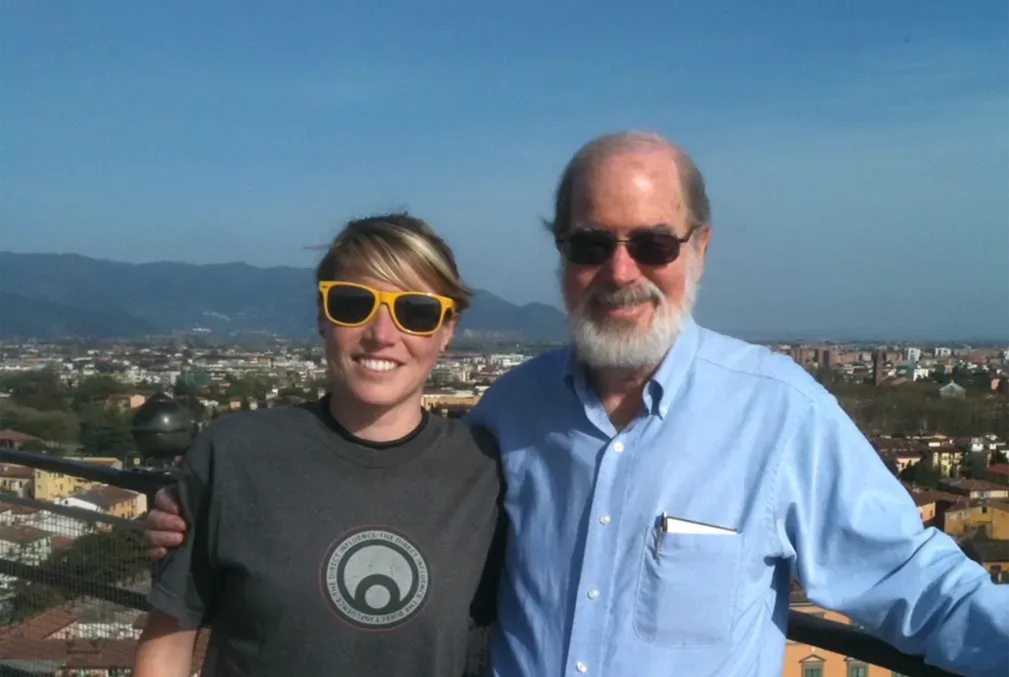

The experience thrilled students (and Jones, who had a cameo in the performance). One student was Chiara Savage Schwartz, a psychology major pursuing a creative writing minor who enjoyed diving deep into both the historical context and the rich body of criticism regarding the play. “I'm never going forget Richard III,” she said. “We came at it from so many angles. There was so much joy in that class.”

Joy — and scholarship. Schwartz was an eager participant in the class email thread, which unearthed that the last time the play was performed at Stanford was 1947. It’s exactly this mix of scholarship and creativity, research and discovery, that embodies what CCSI is all about.