How artists can ‘interrupt’ artificial intelligence

Stanford digital media artist Morehshin Allahyari uses AI in her studio and the classroom to bring creative, critical thinking to the use of the technology that is rapidly becoming ubiquitous.

With image-making tools like DALL-E and Midjourney, artificial intelligence is disrupting the art world, but artists like Morehshin Allahyari are also disrupting AI.

Allahyari, an assistant professor of art and art history in the School of Humanities and Sciences, specializes in using technology to create art while critiquing that technology in the process. In her work as an artist and an educator, she strives to expose the underlying biases of the culture that produces the tech tools with the goal of transforming and improving their use.

We talked with Allahyari about her work with AI, what she has learned from using it—and what AI has learned from her.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: How have you used artificial intelligence in your artwork? What did that process reveal?

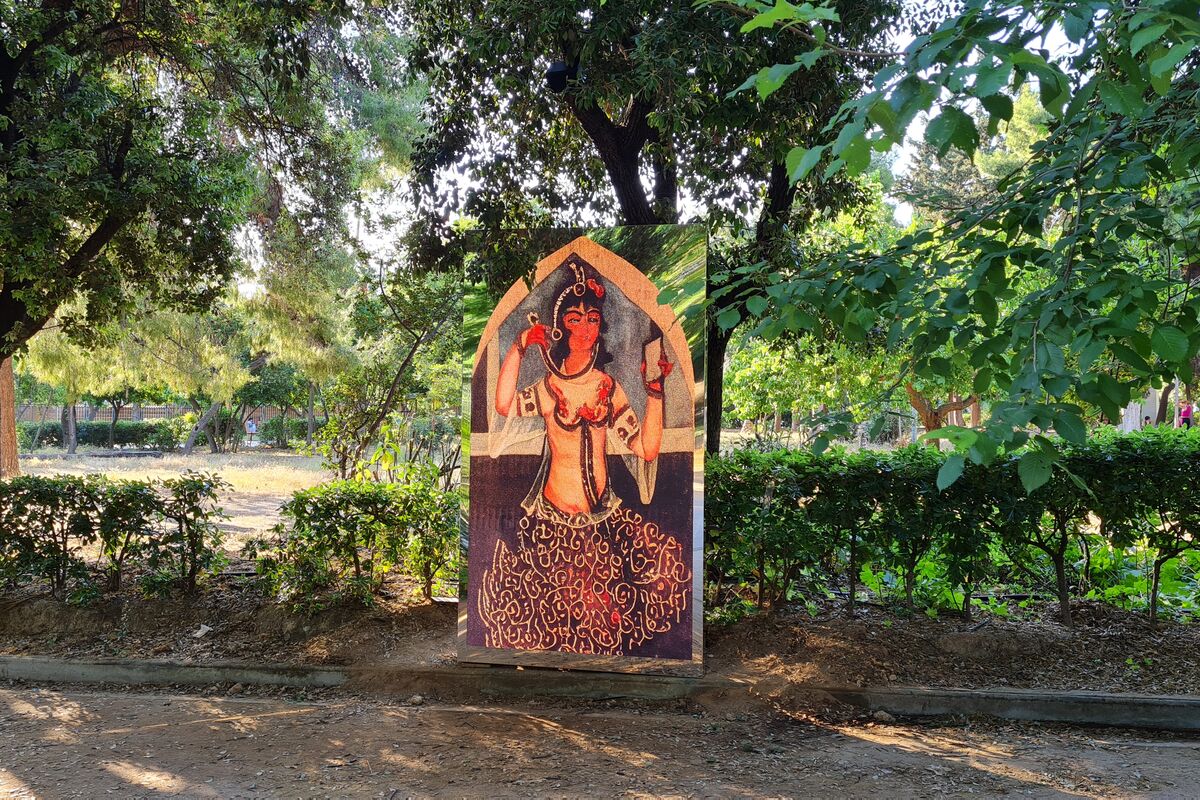

Answer: I did a project called Moon-faced that was informed by the history of gender, gender orientation, and the concept of beauty in Iran during the Qajar dynasty, which existed 350 years ago.

When you look at portraits from this time, you cannot really tell if the subject is a woman or a man. The notion of beauty was not what we have now. For instance, women who had mustaches or unibrows and men who had thinner waists and looked more feminine were considered more beautiful. That shifted toward the end of the 19th century, when Iran was going through Westernization, which basically ended this queer visual culture.

I wanted to train an AI machine to recreate those queer portraits, so I fed it different material and prompts. First, the machine didn't understand the whole Qajar dynasty, which was a very important era within Iranian history and the Middle East in general. It wouldn't create material from that time. That has changed now somewhat with the newer programs. But then, the other problem was the word queer. When I used that word, it would always create images with the rainbow—which obviously is not from that dynasty.

Question: How did you work with AI to bring about the final images you used in Moon-faced?

Answer: It was a bit of collaboration with the machine. I had to find ways to outsmart this tool, to find shortcuts or other ways to get to what I wanted. It's always about understanding what kind of digital libraries these tools are pulling information from. I often talk in my classes about introducing your own materials, creating a type of “decentralized” library, one that is not from the dominant culture. This is one of the examples where I was trying to introduce other material to AI.

If you view the images in this work, you can see that they look restored; the image is not a crystal-clear image that you often get with AI now. I like this notion that things are not perfect. You also get to see how the machine is thinking through something, and that imperfection is part of that process.

Question: You teach a class at Stanford on video and AI. What do you try to have students understand about using these technologies?

Answer: In my class, there are two sections. One is to study an AI tool, like Midjourney, to really understand how it's thinking. There's no technology that is neutral, and AI is the same. So all the injustices that happen in our world, like racism, sexism, xenophobia, etc., are reflected within these technologies. I ask my students to think about these biases and study how they appear in the AI image-making process.

Then after that, I ask them to introduce their own image library. Can they create their own decentralized library with some of these machines? They can upload their own archive of material images and see how that changes the end result. By introducing those, they see if they can interrupt some of that process that otherwise might end with an image that only reflects the dominant monoculture.

As an artist, I use these technologies and these tools, but I also teach my students critical thinking about technology. Instead of saying not to use something that they're going to end up using anyway, I teach them how to use it in a way that is beneficial, how to be smart about it, and then how to take advantage of it. It's like a dance.

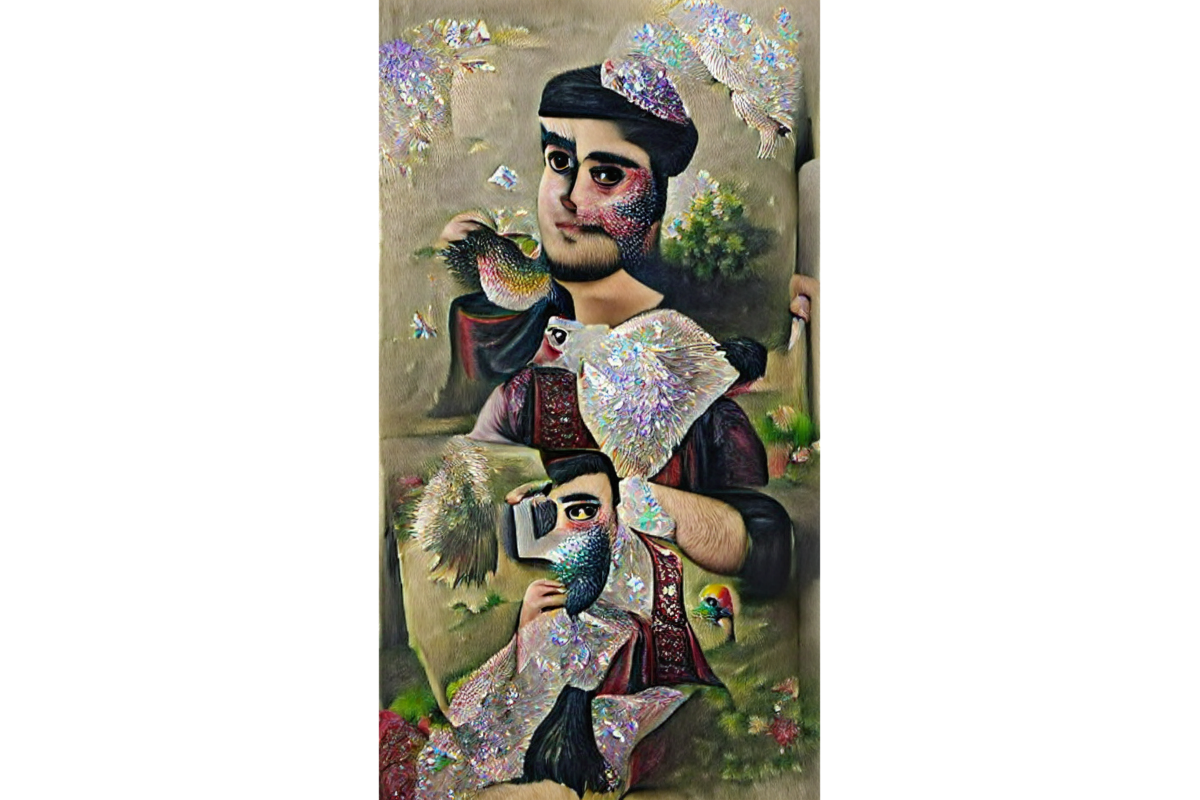

Artwork by Stanford senior Kea Kahoilua Clebsch for the Decolonizing Archives: Video and AI class taught by Morehshin Allahyari. In these pieces, Clebsch used AI to help visualize now-extinct or endangered birds that were part of the practice of creating feather capes within the cultural history of Hawaii. Clebsch inserted these species into the archive of Midjourney, allowing it to create images in which these birds are back in Hawaii's environment.

Question: How can artists inform the development of AI?

Answer: There is this divide between the tech people and the artists, writers, and thinkers who are critical of technology. There have been some attempts with things like artists-in-residence, but we’re not sitting in the meetings where the tools actually get created.

I did do a research project with a Google team to look at different topics in relationship to Islamic regions. And there was a lot of discussion around how we can make AI development and training more inclusive. But there’s another side to the inclusivity effort: While we want to add people of different ethnicities and colors into image libraries used by technology, that work can be used in face recognition training that is also given to the police for use in surveillance. It is complicated.

My hope as an educator is to get younger students, who might end up in these spaces one day, to really think about these issues. The idea of technology for technology's sake is already a failed idea. So then, how can we actually think about it from a different perspective?

Media contact:

Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, 510-872-0340, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)