Investigating Public Policy and Sexual Freedoms

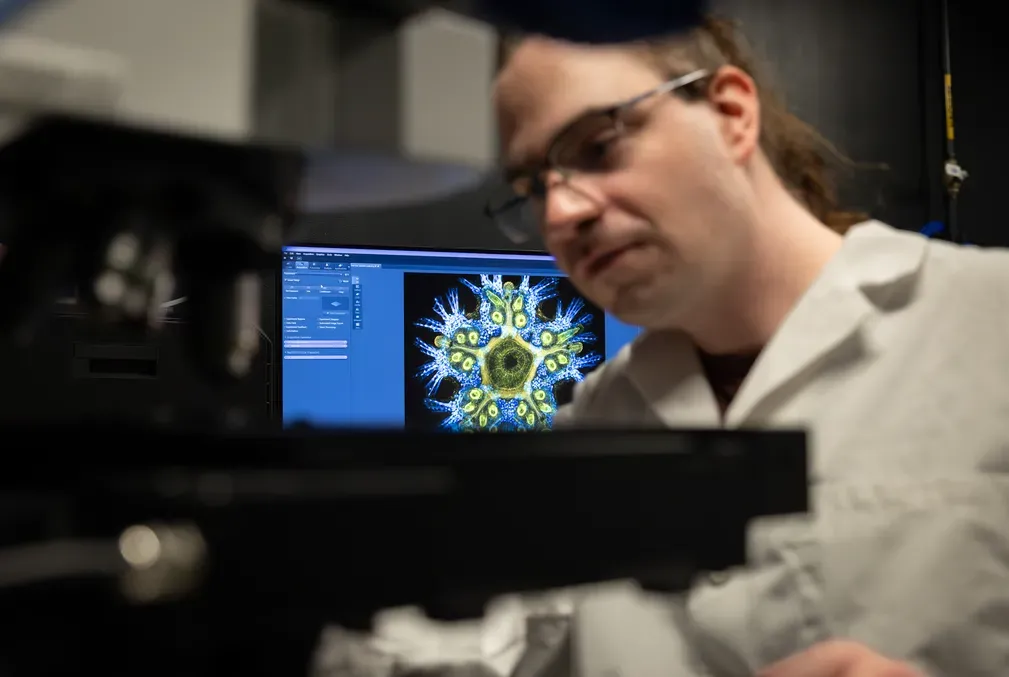

Stanford political scientist Kevin Mintz says his research on sexual freedoms has been shaped by everything from his own experience with cerebral palsy to his encounters with the arts and his study of political theory.

Kevin Mintz, PhD ’19, explores the intersection of political philosophy, U.S. politics, and human sexuality in Stanford’s Department of Political Science. His research interests include disability politics, the application of sexology (the scientific study of human sexuality) to political theory, business ethics, the politics of film and popular culture, and activism for individuals with non-normative sexual and gender identities.

The School of Humanities and Sciences spoke with Mintz about the roots of his dissertation, Sex-Positive Political Theory: Pleasure, Power, Public Policy, and the Pursuit of Sexual Liberation, his interests outside of research, and his plans for after Stanford.

What are the origins of your research interests and how did that transition into your dissertation project?

I was born with a disability, so as challenging as it has been all my life, I was born with a research agenda. But in terms of the sexuality aspect, when I came out seven years ago, I began to realize that the infrastructure that helped me succeed in education and all the other aspects of my life really didn’t talk about my sexuality at all. If I didn’t have parents who were wealthy enough to afford sex therapy, I would still be as confused as ever. That was really the beginning of thinking about how political institutions could extend benefits to people in the realm of sexual health care.

And then a movie called The Sessions starring Helen Hunt came out in 2012 [about a poet paralyzed from the neck down from polio who hires a sex surrogate]. I’ll never forget because I was in London, and the theater I went to wasn’t accessible that day because the elevator was broken. So my friends and I had to go all the way across town to see it. And I knew I had just seen something extraordinary in terms of shaping the discourse around sex and disability. At the same time I was taking a feminist theory class, and we had to do a debate over whether sex work was just as, or more exploitative than, other kinds of domestic labor. That’s where I first read the name “Debra Satz,” because of her related research. She would later become my advisor at Stanford. I got permission to write my master’s thesis on whether surrogate partner therapy should be treated as a legitimate health care service, which then became my first article that was published in The Journal of Philosophy, Science, and Law in 2014.

I knew at the end of that that there was a much bigger story to be told. But I didn’t have nearly enough expertise to tell it effectively so I began looking for ways to become trained in sexuality. During my PhD at Stanford, I spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality in San Francisco. What I learned from my year there was not empirical but really how to assess my own biases and really talk to people about sex in a nonjudgmental way so I could ideally help them by crafting better policy. It was a life-changing experience.

What issues do you specifically explore in your dissertation research?

My dissertation grapples with whether political institutions like health care policy, public schools, and the like have positive obligations to enable people to exercise their sexual liberties. Could you imagine if sexual health and well-being were something that only the rich could afford help in getting? Unfortunately, the entire sex therapy industry has this notion of “We don’t take assistance because we don’t trust the government so stay out of our way.” It’s a fair criticism, but what ends up happening is you have people that spend thousands of dollars out of pocket to get access to help being who they really are. And that’s just sad.

How has your time at Stanford helped shaped your work?

I think my advisor Debra Satz of all people has understood me from day one in a very interesting way because of all the work she’s done on gender equality. That’s why we got special permission from the political science department for her to be my dissertation chair. She’s amazing.

In terms of shaping the actual trajectory of my research, the most important thing Stanford gave me was the opportunity to take my third year to go study at the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality. Because Stanford has no disciplinary boundaries, I was also able to really tell my program what I needed to do to create this research.

And because I believe in both teaching and research, my two quarters of teaching at Stanford were some of the best moments of my life. I not only got to have the joys of seeing young minds grow but I also got several great research assistants out of my former undergrads.

What do you like doing for fun when you aren’t working on your research?

I go to San Francisco, and I live up theater culture, including my personal favorite: "Beach Blanket Babylon," which will be closing in San Francisco soon after a 45-year run. What I really love about the theater, whether it’s opera or a musical, is that it doesn’t matter what you can or cannot do physically. You can just sit in the theater and become absorbed in someone else’s world. It’s immersion into a world so different than your own. Ali Stroker’s victory as the first wheelchair user to win a Tony recently really speaks to how inclusive the arts can be and how important it is to give people with disabilities that kind of outlet.

What does the future hold for you now that you’ve graduated?

I’m going to be a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Clinical Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. I never would have thought I would be going to work for the nation’s leading research hospital. I’m not very fond of the medical system in a lot of ways. A doctor told my family when I was nine-months-old that I would never live a normal life, and I’ve had a lot of interaction with doctors that don’t know how to deal with disabilities beyond treating it or curing it. It wasn’t until my interview with the NIH that I knew where I would spend the next part of my life because the people there are just incredible.

In my postdoc, I will spend half my time doing research with the faculty there — they have a great group of philosophers, lawyers, doctors, all sorts of people who focus on basically applying political theory to health care. But the other half is a clinical training program where everyone in the department gets called in to advise the doctors and researchers at the NIH on what they should do in gray-area ethical situations.

You know, in the classroom you teach these philosophy questions and you have these thought experiments mostly to test student’s thinking, but the outcomes of the thought experiments don’t really matter because they are in your head. But these are some of the most high-stakes thought experiments I’ll probably ever get to work through. And it’s so humbling and exciting to think about everything I’ll learn and experience over the next two years.

___

Mintz holds a bachelor’s in government from Harvard University, a master’s in political theory from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and a Doctorate of Human Sexuality from the Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality. Read more about his time on campus by visiting this portrait, part of the 125th anniversary of Stanford.