Mathematical model calculates probability of shared ancestors for African Americans

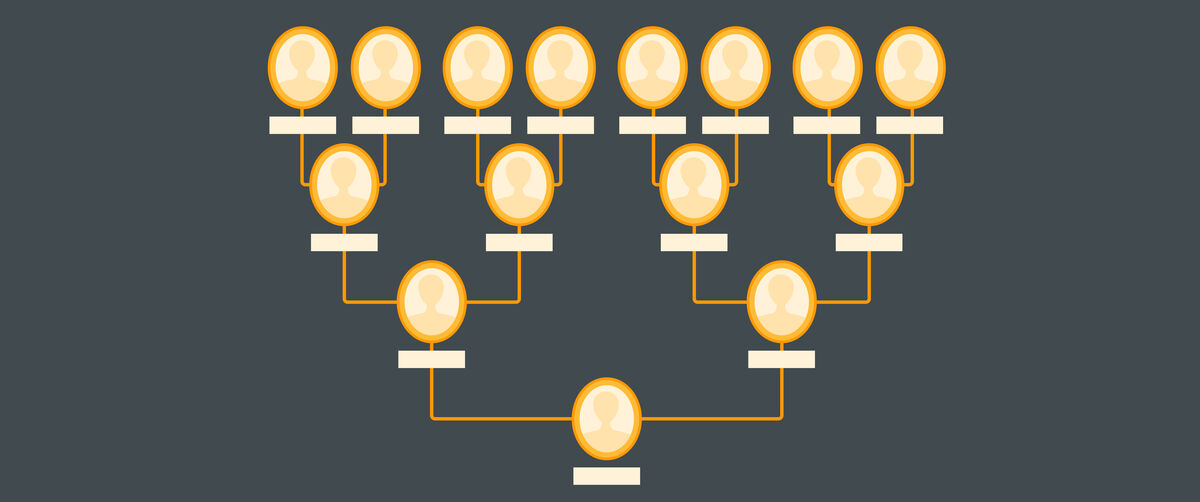

A study from the lab of Stanford geneticist Noah Rosenberg indicates that two African Americans born in the early 1960s have a probability between 19% and 31% of sharing at least one common ancestor who was forcibly transported to the Western Hemisphere during the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

In brief:

Researchers modeled the probability of common ancestors among descendants of Africans who were forcibly transported during the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Sparse record-keeping during slavery means genealogical information is missing for many African American family trees, so mathematical modeling can give some high-level insights.

The study found that two African Americans born in the early 1960s have as much as a 31% probability of having a shared ancestor who arrived as an enslaved person in North America from the early 1600s to 1860.

Calling a friend “cousin” might not be just a term of affection among some African Americans. Now, a mathematical model shows that there is a good chance there is some type of family connection between 185 and 410 years ago for many pairs of African Americans of the same age.

The study, published in the journal American Statistician, takes into account this country’s dark history of slavery in an attempt to shed some light on the heritage of African Americans. Because of the lack of good records, many African Americans have limited potential to learn about their ancestry before the 1870 census.

The research found that for two randomly selected African Americans born from 1960 to 1965, there is a probability between 19% and 31% that they share at least one African ancestor who was forcibly transported across the Atlantic. For the next generation, specifically those born between 1985 and 1990 to two African American parents, that percentage rises even higher, above 50%— the flip of a coin.

“We used a mathematical model of genealogies to see what might be found in families where the precise story is not known,” said Noah Rosenberg, the study’s senior author and professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “We found that there is a surprisingly high probability that two people share an ancestor who arrived as an enslaved person during the Transatlantic Slave Trade. That’s interesting both in terms of the relatedness of the population and the shape of American demographic history.”

For this study, the researchers created their model of genetic ancestry by using a famous statistical problem called “the birthday problem,” sometimes used in elementary school classrooms to illustrate how probability works. Given that there are a limited number of days, 365, in a year, there is a good chance that in any classroom group there will be at least two students who have the same birthday. For example, in a group of 23 students, the chance is above 50% that there will be a match. Expand that group to over 50 students, and there’s a 97% chance of at least two people with the same birthday.

A slight variation on the birthday problem involves the probability that two people in different classrooms would share the same birthday. Rosenberg and his colleagues recognized that there are similar statistics at work with people whose ancestors experienced the same historical event.

In this study, the researchers estimated that African Americans born in the early 1960s each have about 300 ancestors among the estimated 400,000 to 500,000 Africans transported to North America from the early 1600s to 1860. Then, it was a matter of figuring out the likelihood that one person’s group of 300 ancestors overlapped with that of another person.

Moving forward a generation, to African Americans born in the 1980s, the number of ancestors increases along with the possibility of sharing an ancestor with another person of the same generation.

Other research has tried to fill in the knowledge gaps in African American ancestry using genetic methods, including an earlier investigation from Rosenberg’s lab that helped estimate the number of African and European genealogical ancestors in typical family trees.

While the current study is not designed to make connections between specific descendants and ancestors, mathematical modeling can help provide some clues about shared heritage, Rosenberg said.

“In most cases, the question of whether two specific people have a shared transported ancestor cannot be directly answered because many aspects of the history of slavery led to profound loss of genealogical information,” he said. “A mathematical model therefore has potential to make a meaningful contribution.”

Acknowledgments:

Additional Stanford co-authors on this study include first author Lily Agranat-Tamir and Kennedy D. Agwamba, both postdoctoral scholars in biology. Jazlyn A. Mooney, a former postdoctoral scholar in Rosenberg’s lab and currently an assistant professor at the University of Southern California, is also a co-author.

Rosenberg is also a member of Bio-X and the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering.

Media contact:

Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, 510-872-0340, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)