Q&A: Paul R. Ehrlich on his life’s work

Stanford population ecologist and environmental activist Paul R. Ehrlich discusses his new autobiography, Life: A Journey Through Science and Politics.

Most scientists have an area of expertise; Paul R. Ehrlich has many. In a career spanning more than 60 years, Ehrlich, the Bing Professor of Population Studies, Emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences and Senior Fellow, Emeritus, at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment has authored or co-authored more than 40 books and 1,200 papers on topics as diverse as co-evolution in butterflies and flowering plants, jaw size in humans, and overpopulation.

At Stanford, Ehrlich founded the Center for Conservation Biology, co-founded the Human Biology Program, and with Richard Holm established Jasper Ridge as a research reserve. He has used his platform as a respected scientist and bestselling author to call attention to environmental issues, including overpopulation, the importance of biodiversity, and the degradation of the planet’s natural resources and ecosystems. He has advocated for gender and racial equality in numerous forums and has guest-starred in more than 1,000 news and television segments, including more than 20 appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

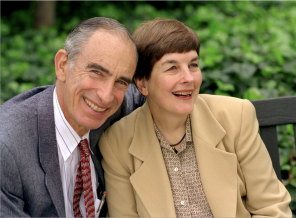

In his new autobiography, Life: A Journey Through Science and Politics (Yale University Press, 2023), Ehrlich, now 90, reveals the rich and candid backstories behind his scientific achievements. He details his groundbreaking research with Peter Raven on caterpillar-host plant relationships; the origins and aftermath of The Population Bomb (Sierra Club/Ballantine Books, 1968), the bestseller he wrote with senior researcher Anne Howland Ehrlich, his wife and co-author on several books; and his many forays into politics and advocacy. Ehrlich also pulls the curtain back on some of the more private moments in his life by recounting milestones and memories with Anne and tales from his childhood.

“I’ve been buried in life,” Ehrlich writes at the start of his book, and for a researcher seemingly immersed in all aspects of life on Earth, that certainly could be true. But the gravity and breadth of his work hasn’t weighed him down. Instead, Ehrlich seems buoyed by it—it has given him a platform and a purpose. Here, Ehrlich discusses his book, his research, and the messages he hopes people will glean from both.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: What inspired you to write this book, and what message do you hope people will take from it?

Ehrlich: In part I wanted to answer some questions about my career for young friends and colleagues and, especially, my grandchildren. I also wanted to show, by example, what a wonderful career science can provide if siloing—restricting one’s investigations and interests to a narrow area—is avoided. Similarly, I wanted to emphasize that scientists should not just “give the facts” but also be activists when their results make it appropriate. You don’t surrender the right to free speech by becoming a scientist.

Question: You state that your “love for the beauty of the planet and its inhabitants” is a theme that runs implicitly through the book. Is this a theme for your work as well?

Ehrlich: The main theme that has driven my work is curiosity. I’ve read and traveled widely, and questions kept popping up. Why do different species of reef fishes school together? How does crowding influence people’s behavior? How are butterfly groups related to the plants their caterpillars eat? Why are human jaws shrinking?

Question: Was there anything that didn’t make it into the book that you wish you could have included?

Ehrlich: The most important thing in my life has been Anne and my many other friends. A few of the latter I forgot to mention, and virtually none of them got the attention in Life they deserved. For example, my mentors Charles Michener, Bob Sokal, and Joe Camin had much more influence on me than I could relate in the book as did Dick Holm when I first got to Stanford. Human beings are described as hypersocial, and that descriptor fits me perfectly.

Question: You were a correspondent for NBC News and a frequent guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. What was the most valuable part of those experiences for you?

Ehrlich: I quickly learned the educational value of big-time television. My first appearance on The Tonight Show brought the biggest rush of mail in the history of the city of Los Altos, then the site of Zero Population Growth headquarters (now located in Washington, D.C., and known as the Population Connection). Subsequent invitations to speak supplied me with many opportunities to do field work in distant places.

Question: Scientists are encouraged to share their research widely, but many find it challenging. What would you say to researchers who would like to share their work with the public but aren’t sure where to start or are unsure if they will “get it right?”

Ehrlich: A bunch of my colleagues, especially Jane Lubchenco and Pam Matson, set up the Aldo Leopold fellowship to help midcareer scientists solve this problem by giving them opportunities to train for and practice interactions with the public, policymakers, the media, and others. On 9/11—a horrific tragedy—I happened to be in Washington, D.C., with the program training a group of fellows to handle TV “ambush interviews.” Every scientist’s education should include training in public speaking and an important starting point is giving seminars and asking for critiques of your presentation.

Question: What are you most proud of?

Ehrlich: The wonderful students who I helped have fun lives and the degree to which they and Anne and I have managed to alert people to the existential threats to civilization from overpopulation, overconsumption, inequity and growthmania, destruction of human life-support systems, and the increasing likelihood of nuclear war.

Question: In the chapter titled “Combatting the Forces of the Endarkenment,” you discuss the role that universities like Stanford could play in coping with the environmental crisis and highlight the need for universities to adopt something like a phenomenon-based learning framework. Can you share more about this?

Ehrlich: Stanford is clearly one of the top universities globally, but like all the other great universities, it has a discipline, subject, and department structure based on the antique ideas of Aristotle. In 2016, Finland mandated the use of Phenomenon-Based Learning in middle schools, which teaches students about phenomena as multifaceted entities. In such an approach, students would learn to understand an issue like sustainability through the lenses of overpopulation and resource use, overconsumption, patterns of governance, inequity, the importance of narrative and messaging in communication, art, value and how it is quantified, the ethics of national boundaries, history, and technologies and their environmental costs (to name a few of the most important) without worrying about “subject” boundaries. If departments disappeared and a new problem-oriented structure similar to the Finnish middle school approach were adopted, it would break down the siloed nature of education and help students learn to solve big problems. This shift would allow universities to become a beneficial influence on the trajectory of civilization during the “great acceleration.” I would love to see Stanford, which has been so good to me, become the first major university to lead the way in an educational revolution that could stretch from kindergarten to adult education.