Quantum measurements induce new phases of entanglement

Researchers harness “quantum weirdness” to observe “spooky” measurement-induced phases of quantum information and teleportation in one of the largest digital quantum experiments to date.

Harnessing the “weirdness” of quantum mechanics to solve practical problems is the long-standing promise of quantum computing. But much like the state of the cat in Erwin Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment, quantum mechanics is still a box of unknowns. Similar to the solid, liquid, and gas phases of matter, the organization of quantum information, too, can assume different phases. Yet unlike the phases of matter we are familiar with in everyday life, the phases of quantum information are much harder to formulate and observe and as a result have been only a theoretical dream until recently.

Measurements are arguably the weirdest facet of quantum mechanics. Intuition tells us that a state has some definite property and measurement reveals that property. However, measurements in quantum mechanics produce intrinsically random results, and the act of measurement irreversibly changes the state itself. Unlike laptops, smartphones, and other classical computers that rely on binary “bits” to code in the state of 0 (off) or 1 (on), quantum computers use “qubits” of information that can be in the state of 0, 1, or 0 and 1 at the same time, a concept known as superposition. The act of measurement doesn’t just extract information, but also changes the state, randomly “collapsing” a superposition into a specific value (0 or 1).

Moreover, this collapse affects not just the qubit that was measured, but also potentially the entire system—an effect described by Einstein as “spooky action at a distance.” This is due to “entanglement,” a quantum property that allows multiple particles in different places to jointly be in superposition, which is a key ingredient for quantum computing. The collapse of an entangled state can also enable spooky phenomena such as “teleportation,” thereby irretrievably altering the “arrow of time” (the concept that time moves in one forward direction) that governs our everyday experience.

In other words, measurements can be used to fundamentally reorganize the structure of quantum information in space and time.

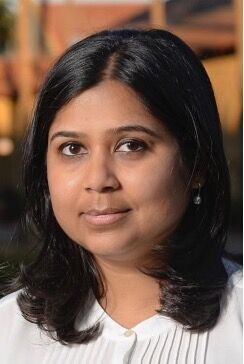

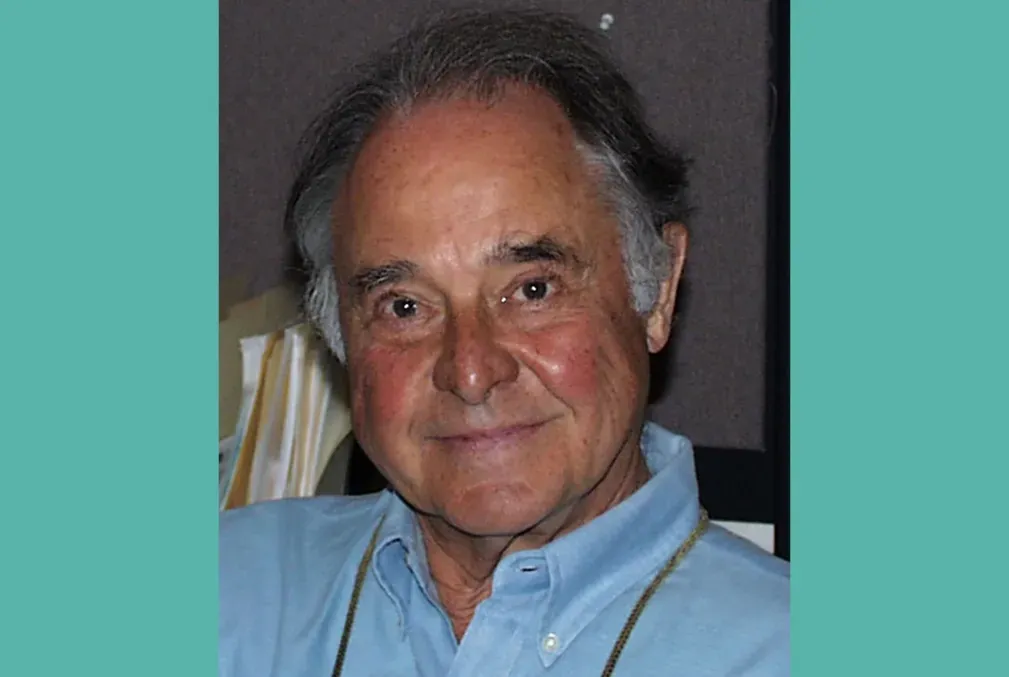

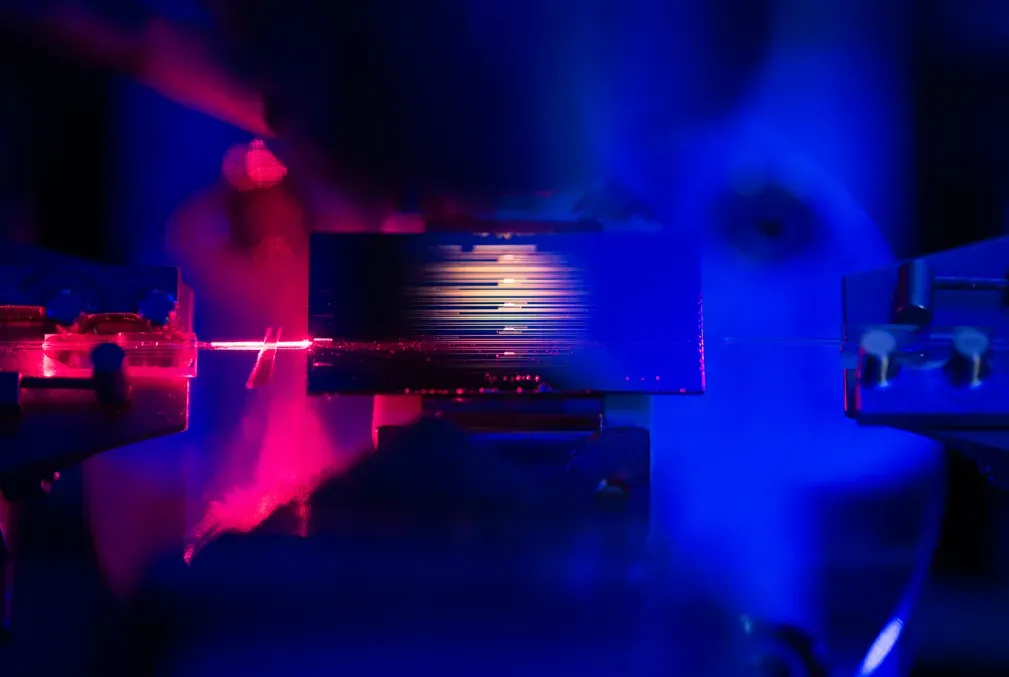

Now, a new collaboration between Stanford and Google Quantum AI investigates the effect of measurements on quantum systems of many particles on Google’s quantum computer and has obtained the largest experimental demonstration of novel measurement-induced phases of quantum information to date. The study was co-led by Jesse Hoke, a physics graduate student and fellow at Stanford's Quantum Science and Engineering initiative (Q-FARM), Matteo Ippoliti, a former postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Physics, and senior author Vedika Khemani, associate professor of physics at the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and Q-FARM. Their results were published Oct. 18 in the journal Nature.

Here, Hoke, Ippoliti, and Khemani discuss how they observed measurement-induced phases of quantum information—a feat once thought to be beyond the realm of what could be achieved in an experiment—and how their new insights could help pave the way for advancements in quantum science and engineering.

Question: What distinguishes the phases investigated in this study from one another, and what is teleportation?

Ippoliti: In the simplest case, there are two phases. In one phase, the structure of quantum information in the system forms a strongly connected web where qubits share a lot of entanglement, even at large spatial distances and/or temporal separations. In the other, the system is weakly connected, so correlations like entanglement decay quickly with distance or time. These are the two phases that we probed in our experiment. The strongly entangled phase enables teleportation, which occurs when the state of one qubit is instantly transmitted, or “teleported,” to another far away qubit by measuring all but those two qubits.

Question: How did you control when a phase transition occurred?

Khemani: The competing forces at play are the interactions between qubits, which tend to build entanglement, and measurements of the qubits, which can destroy it. This is the famous “wave function collapse” of quantum mechanics—think of Schrödinger’s cat “collapsing” into one of two states (dead or alive) when we open the box. However, because of entanglement, the collapse is not restricted to the qubit we directly measure but affects the rest of the system too. By controlling the strength or frequency of measurements on the quantum computer, we can induce a phase transition between an entangled phase and a disentangled one.

Question: What were some of the challenges your team needed to overcome to measure quantum states, and how did you do it?

Ippoliti: Measurements in quantum mechanics are inherently random, which makes observing these phases notoriously challenging. This is because every repetition of our experiment produces a different, random-looking quantum state. This is a problem because detecting entanglement (the feature that sets our two phases apart) requires observations on many copies of the same state. To get around this difficulty, we developed a diagnostic that cross-correlates data from the quantum processor with the results of simulations on classical computers. This hybrid quantum-classical diagnostic allowed us to see evidence of the different phases on up to 70 qubits, making this one of the largest digital quantum simulations and experiments to date.

Hoke: Another challenge was that quantum experiments are currently limited by environmental noise. Entanglement is a delicate resource that is easily destroyed by interactions from the outside environment, which is the primary challenge in quantum computing. In our setup, we probe the entanglement structure between the system’s qubits, which is destroyed if the system is not perfectly isolated and instead gets entangled with the surrounding environment. We addressed this challenge by devising a diagnostic that uses noise as a feature rather than a bug—the two phases (weak and strong entanglement) respond to noise in different ways, and we used this as a probe of the phases.

Khemani: In addition, we used the fact that the “arrow of time” loses meaning with measurement-induced teleportation. This allowed us to reorganize the sequence of operations on the quantum computer in advantageous ways to mitigate the effects of noise and to devise new probes of the organization of quantum information in space-time.

Question: What do the findings mean?

Khemani: At the level of fundamental science, our experiments demonstrate new phenomena that extend our familiar concepts of "phase structure." Instead of thinking of measurements merely as probes, we are now thinking of them as an intrinsic part of quantum dynamics, which can be used to create and manipulate novel quantum correlations. At the level of applications, using measurements to robustly generate structured entanglement is inspiring new ways to make quantum computing more robust against noise. More generally, our understanding of general phases of quantum information and dynamics is still nascent, and many exciting surprises await.

Acknowledgements

Hoke conducted research on this study while working as an intern at Google Quantum AI under the supervision of Xiao Mi and Pedram Roushan. Ippoliti is now an assistant professor of physics at the University of Texas at Austin. Additional co-authors on this study include the Google Quantum AI team and researchers from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Auburn University; University of Technology, Sydney; University of California, Riverside; and Columbia University. The full list of authors is available in the Nature paper.

Ippoliti was funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative. Khemani was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences; the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; and the Packard Foundation.