Stanford scholar traces the roots of South Korea’s cosmetic surgery surge

Stanford scholar So-Rim Lee details the historical, cultural, and economic influences on the surge of the cosmetic surgery industry in South Korea.

Growing up in the Gangnam district of Seoul, South Korea, in the 1990s, So-Rim Lee watched her quiet, residential neighborhood transform into the bustling and posh commercial center that it is today—the playground for the rich that the Korean singer Psy mocked in his 2012 international hit “Gangnam Style.”

As time went on, Lee noticed that many of the people she encountered on her way to school sported compression bandages on their faces. Later, she would learn that these were patients recovering from cosmetic surgery. Lee, who received her doctorate from Stanford’s Theater and Performance Studies (TAPS) department this year, was witnessing the explosion of South Korea’s elective surgery industry.

Today, the nation hosts the world’s highest number of such procedures per capita—around one in five South Korean women have had work done, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (that number climbs to one in two among twenty-something women in Seoul). Gangnam’s so-called “beauty belt” contains 400-500 cosmetic surgery clinics in a single square mile, catering both to locals and to foreign “medical tourists.”

Lee became curious. What social and economic forces, she wondered, were spurring her neighbors, friends, and family members to go under the knife?

This question followed Lee to Stanford in 2012 and eventually became the seed of her recently completed dissertation, “Performing the Self: Cosmetic Surgery and the Political Economy of Beauty in Korea.”

By tracing South Korea’s obsession with surgical enhancements to long entrenched historical and cultural influences, as well as harsh economic realities of the present day, Lee seeks to spark a more humane, nuanced conversation about the practice in both academic and popular spheres.

A turn in the patient chair

One way that Lee attempts to de-stigmatize cosmetic surgery is by making use of auto-ethnography, an anthropological method by which the researcher incorporates her own experiences into her analysis. An important source for Lee’s dissertation are her diaries from the 1990s, in which she recorded her encounters with Gangnam’s burgeoning cosmetic surgery scene.

She has supplemented these recollections with frequent research trips to South Korea, funded by Stanford resources including the Mellon Dissertation Fellowship, the Ric Weiland Graduate Fellowship, the Graduate Research Opportunity Award, the Center for East Asian Studies, and the TAPS department.

Traveling home has allowed Lee to talk with cosmetic surgeons and clients about their experiences—and even to take a turn in the patient’s chair herself. In 2014, Lee signed up for a temporary cheek-plumping injection in order to gain a more personal understanding of the processes she was studying. “It hurt!” she recalls with a laugh. The five-minute shot, whose speed and ease have earned it the nickname “lunchtime filler,” “reminded me of when I got my tattoo,” she says.

Lee’s project also departs from existing work on the subject in terms of its racial politics. “Much scholarship and journalism on cosmetic surgery comes from Euro-American and Australian feminists,” she notes. This can give their writings on Korea an orientalist, patronizing undertone. For instance, some writers assume that Koreans are driven to undergo the notorious double-eyelid modification, which aims to give the eye a wider look, because they want to “look white.”

The reality, Lee contends, is much more complex. Although some of these beauty ideals do have a racialized history, she says, race is no longer central to modern-day Koreans’ choices to modify their appearance. “Korean people who receive cosmetic surgery clearly don’t look ‘white’ afterwards, nor do they consciously seek to do so,” she says. “Instead, they more often just look like Korean people who have had surgery.”

For instance, jaw-reduction surgery—among the most common procedures in Korea—has no evident connection to Caucasian features. Nor is double-eyelid surgery the sole domain of Asians: it is also commonly sought out by white women seeking to look younger, indicating perhaps that large eyes have a cross-cultural appeal.

Gwansang

Lee’s research reveals that modern Koreans’ investment in appearance has its roots in an ancient custom known as gwansang—fortune-telling based on facial physiognomy.

The belief system, which dates back to approximately the seventh century, holds that the features of a person’s face comprise a “map” that reveals his personality, as well as his past, present, and future, Lee says.

This idea that one’s identity is physically encoded became connected to ethnicity during the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910-1945). Japanese rulers insisted that certain facial traits bespoke greater racial intelligence and nobility (perhaps unsurprisingly, Japanese features were deemed a civilizational cut above those of Koreans).

Such beliefs created a receptive environment for ethnic cosmetic surgery techniques that were imported by U.S. doctors during and after the Korean War (1950-53), Lee says. D.H. Millard, a U.S. surgeon sent to South Korea to perform reconstructive surgery on the war’s many wounded, popularized what he called “deorientalizing” surgeries, including double-eyelid procedures, in the country.

It was perhaps during this time, says Lee, that Koreans’ gwansang-derived conviction in fixed destiny began yielding to Euro-American notions that it was possible to change that destiny by changing one’s face and body.

From the ’60s onward, the Korean cosmetic surgery industry grew into a force to be reckoned with, eventually producing the moment in which contemporary South Korea finds itself—one whose zeitgeist Lee sums up in a popular Korean saying: “Your god creates you, but your doctor-god really re-makes you.”

Economic pressures

Lee contends that South Korea’s already high cultural investment in appearance was brought to new heights by an economic event in the late 20th century.

During the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, Korea’s markets collapsed, spurring the International Monetary Fund to forcibly restructure Korea’s government-run economy into one that more closely resembled the privatized free markets of Western nations.

Korea’s previously strong labor protections were removed, making it far easier for corporations to fire their workers. This and other factors have generated an unemployment crisis that has lasted to the present.

In today’s fiercely competitive job market, Koreans pay for nips and tucks in order to better their job prospects. This occurrence is so common that it has been given its own name, “Chwieop Seonghyeong” (“employment surgery”).

And looks do indeed matter, Lee says: until the government outlawed the practice in 2017, Korean jobseekers were often required to include a photo with their application materials, and, in a recent survey, roughly 50 percent of hiring managers in Korea said they had based job offer decisions on applicants’ appearances.

These economic transformations were accompanied by psychological ones. Advocates of the nation’s newly free market argue that privatization permits each person to control her own career success, rather than relying on state-managed jobs—an attitude that shifts the blame for any financial failures from broader economic systems to the individual herself.

Today, Lee observes, if you are out of a job, or without romantic prospects, many Koreans would “say it is all your fault because you are the controller of your life.”

Thus, says Lee, plastic surgery has become “a kind of strange elective necessity” for members of the middle and upper classes: Undergoing a tasteful amount of cosmetic surgery signals to the world that one is “the right kind of person, one who takes care of him or herself,” Lee says.

Draw on me

But Lee’s dissertation also highlights Korean thinkers who are pushing back against their culture’s worship of instant gratification.

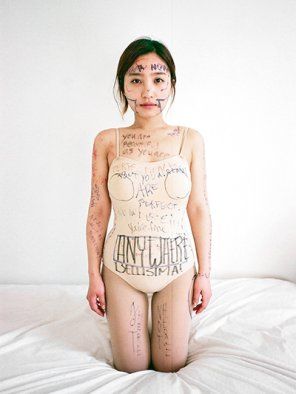

Among others, Lee interviewed Ji Yeo, a Korean-born artist whose photography series Beauty Recovery Room (2014) documents the bruised and bandaged flesh of Korean patients in the hours immediately following their elective surgeries. The images confront audiences with the unsavory aspects of bodily modification that are “socio-culturally customary to keep private,” Lee says.

Another work by Yeo, the performance piece Draw on Me (2011), invited onlookers on a busy New York street to brazenly assess her body. Wearing only a skin-toned leotard and tights, Yeo held a sign inviting passersby to write on her flesh with a marker to indicate where she should get cosmetic surgery.

By the piece’s conclusion, Yeo’s skin was covered in inky judgements of her body and face. This unsettling end product makes visible the psychic damage that any looks-obsessed culture, from the U.S. to Korea, can inflict on its members, Lee says.

An everyday performance

Lee’s dissertation is the first book-length project to frame Korean cosmetic surgery in the context of performance studies.

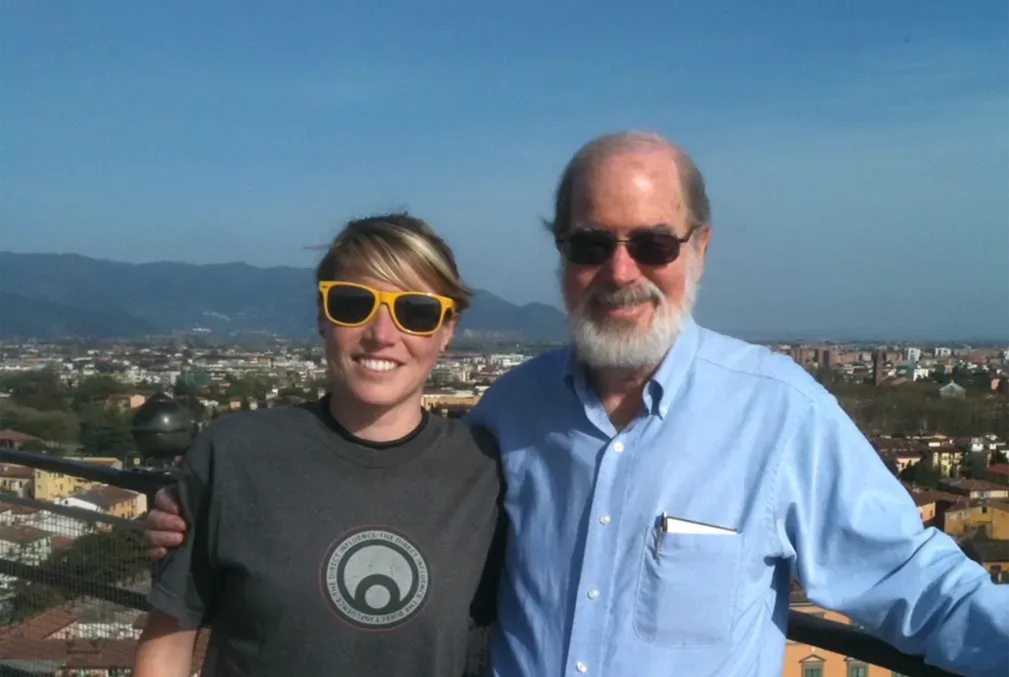

Lee’s advisor at Stanford, Professor Branislav Jakovljevic, believes her project heralds a new era for performance studies scholarship on Korea, which has historically tended to paint Asian cultures’ theatrical traditions as ancient and fundamentally alien to those of the West.

So-Rim’s project brings TAPS’ engagement with East Asia “up to the present by focusing on very current, cosmopolitan, and global performances,” says Jakovljevic, an associate professor of theater and performance studies and the department chair of TAPS.

Lee, who is now a postdoctoral scholar at Columbia University, ultimately argues that cosmetic surgery is not a monstrous aberration that veers from social norms but merely one of the many ways in which people—Koreans, Americans, and Europeans alike—painstakingly craft their physical appearances.

She notes that we all fine-tune our bodies and personalities—consciously or otherwise—for audiences composed of our peers: We lose weight, buy flattering clothing, wear make-up, and carefully edit our social media profiles.

Trying to look attractive is, Lee says, always a type of performance—one that unfolds not on a stage, but rather in the small, everyday acts we employ to present a curated version of ourselves to the world.