Stanford scholars report French headscarf ban adversely impacts Muslim girls

French ban on headscarves in public schools hindered Muslim girls’ ability to finish school.

The French ban prohibiting Muslim girls from wearing headscarves in public schools has been shown by two Stanford political scientists to have had a detrimental effect on both the girls’ ability to complete their secondary education and their trajectories in the labor market.

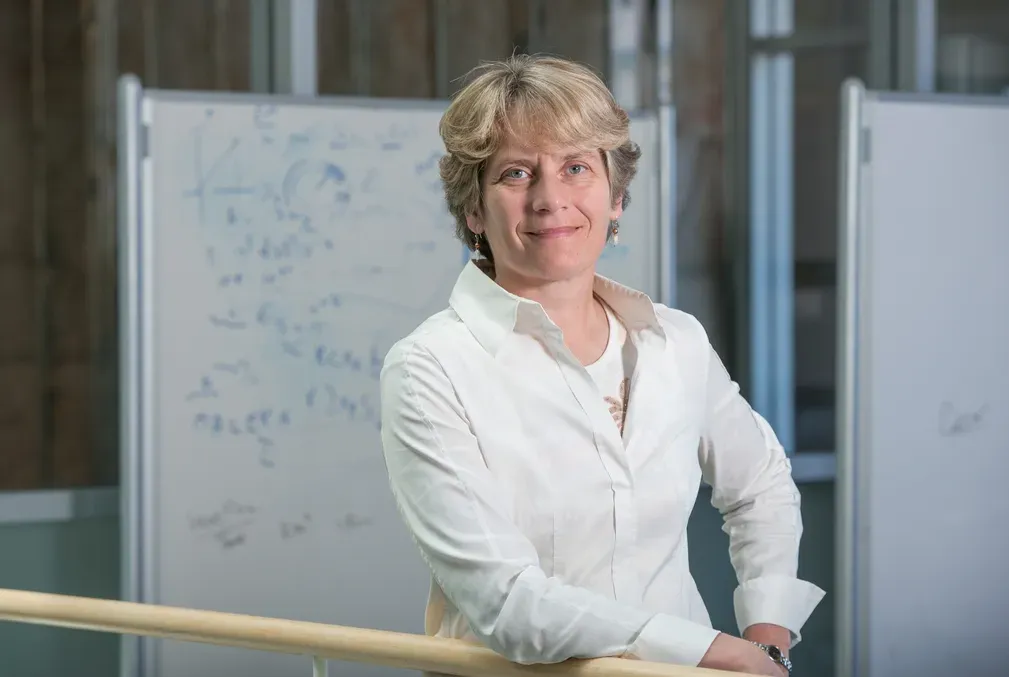

In a paper published last month in the American Political Science Review, Vasiliki Fouka, assistant professor of political science in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, and Aala Abdelgadir, a doctoral candidate in political science, found that the 2004 ban led to increased perceptions of discrimination, which hindered Muslim girls from finishing school.

The scholars also found that the ban strengthened both national and religious identities for young Muslim women who were most affected by it. This nuanced picture could be seen to be at odds with the intended goal of the ban, which was to reduce the visibility of religion in the public sphere in accordance with French values.

“I think we have, from different contexts, quite a bit of evidence that these types of prescriptive policies are likely to backfire,” Fouka said. The scholars write that one way of interpreting their findings—based on insights from interviews they conducted—is that native-born children of immigrants are redefining what it means to be a citizen of a Western country. Many are asserting that existing notions of national identification should be broadened to make room for expressions of cultural and religious differences.

Using evidence to determine effects

“In response to rising immigration flows and the fear of Islamic radicalization, several Western countries have enacted policies to restrict religious expression and emphasize secularism and Western values,” the co-authors write. “Despite intense public debate, there is little systematic evidence on how such policies influence the behavior of the religious minorities they target.”

In order to provide that systemic evidence on the effect of the French ban, Fouka and Abdelgadir used data from the French Labor Force Survey, the French census, and a representative survey of immigrants and immigrant-descendants. These sources were used to compare differences between Muslim and non-Muslim women who were born earlier than 1986, and had likely left secondary education by the time the ban was enacted and those born in 1986 or later, who were affected by the ban. The latter group was young enough to be at school when the law was enacted in 2004 and then could be followed for many years after the ban went into effect.

The French law banned the use of religious signs and garments in primary and secondary public schools in France. While it did not single out particular symbols or religions—large Christian crosses, Sikh turbans, and Jewish yarmulkes were included in the ban—the authors contend that it most widely affected Muslim schoolgirls.

Educational disruptions

Fouka said the most notable disruptions occurred during the period of the ban's implementation. While Muslim women born before the ban took effect were less likely than non-Muslim women to complete secondary education, which in France covers students ages 11–18, this gap more than doubled for the group that was born after 1986. This was particularly true for those aged 16-18 in 2004, who under French law, were allowed to drop out of school.

The study also found that the number of Muslim girls who were adversely affected was much higher than the number of girls who wore veils before the ban took place. The scholars contend that this points to a discriminatory culture in the schools that had a negative impact on a broader population of Muslim schoolgirls, not just those who chose to veil, by calling more attention to how they dressed.

“This perceived discrimination has a big effect particularly in the adolescent years,” Fouka said. The data showed that school-aged Muslim girls reported higher discrimination in school, but not in other contexts, such as in the streets, stores, or while obtaining public services.

Another finding is that Muslim women affected by the ban took longer to complete secondary education and were more likely to have repeated a class. Among 20-year-old non-Muslims, only about 7.9 percent were still attending secondary education. For Muslims this share is 13.3 percent, a difference the scholars attribute largely to the effects of the veiling law.

Ongoing impacts

After the implementation of the ban, girls were required to come to school unveiled. If they failed to do so, girls were required to enter into mediation to discuss their options. If negotiations failed, they were expelled from school. Their options were then to leave the education system (if older than 16), switch to private school, pursue distance learning, or leave the country.

By conducting interviews with women who were affected by the policy, the scholars sought to add a human element to the data. Twenty-eight-year-old Nadia, who started veiling at age 13, told the scholars that her teachers tried and failed to convince her to unveil. This occurred, the scholars note, before the ban went into effect, when school officials were allowed to decide how they would approach the issue, and Nadia’s school decided to ban headscarves. Her story is included as an illustration of the processes involved, because they are similar to those girls faced after the ban.

The school suspended Nadia and engaged a government mediator to resolve the impasse. While her parents, concerned about her education, ultimately convinced her to unveil and return to school, the protracted mediation process led her to fall behind relative to her peers. “Her experience illustrates how outlawing veiling in schools directly disrupts the educational trajectories of veiled Muslim girls, with the potential to undermine their academic performance,” the scholars write.

The lack of or delay in completing secondary education also was found to have longer-term consequences through lower participation in the labor force, lower employment rates, and higher likelihood of living with parents. The study found that the veiling law widens the employment gap by more than a third, the labor force participation gap by more than half, and the gap between Muslims and non-Muslims in cohabitation with parents by more than a third.

Movement in two directions

Bans, such as the French law, have been proposed in many countries to further assimilation among immigrant populations. In the context of the French headscarf law, Fouka and Abdelgadir found that on average, women exposed to the ban showed an increase in both French and religious identities.

Several women continued to veil, while at the same time maintaining that they were as French as anyone else. "Some interviewees did choose to integrate on their own terms, by maintaining their veils and French values,” the authors write. “As one respondent put it, she was born in France, she speaks the language, and she respects the laws, and therefore she was as French as any other citizen."

However, the headscarf ban led many of those who reported a stronger connection to their religious community to begin with to strengthen that connection even more. Some respondents chose to retreat from French society and moved closer to their Muslim identity, which for some girls may have meant putting on the hijab as an act of resistance or attending a school where children of immigrants predominate.