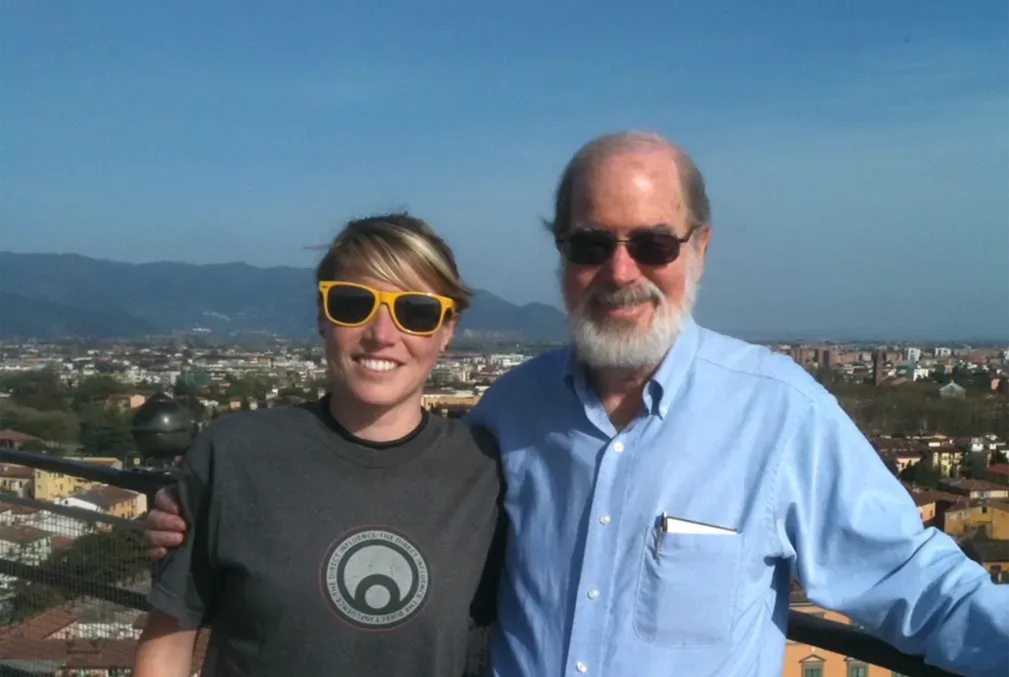

Jean-Marie Apostolidès, literary scholar and dramatist, dies at 79

A professor emeritus of French and Italian and of theater and performance studies, Apostolidès was interested in avant-garde artistic movements and the Marxist-adjacent social revolutionaries inspired by them.

Jean-Marie Apostolidès, the William H. Bonsall Professor in French, Emeritus, who drew on his knowledge of literature, psychology, and anthropology to investigate an eclectic range of subjects, died of cancer on March 22 at his home on the Stanford campus. He was 79.

A professor emeritus in the departments of French and Italian and Theater and Performance Studies in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, Apostolidès wrote about Cyrano de Bergerac, Tintin, King Louis XIV, and the Unabomber’s manifesto, among many other topics. He was especially interested in French classical literature and avant-garde artistic movements, including the Marxist-adjacent social revolutionaries inspired by them. He also wrote plays, essays, and works of fiction, including two graphic novels with the Canadian artist Luc Giard, and directed theater productions and short films.

“Those of us who knew Jean-Marie well will always remember his vibrant intellectual imagination, his personal charm and quirks, his ever-thickening French accent in English, his generosity toward colleagues and students, his superabundant vitality, and his winsome smile,” wrote Robert Harrison, the Rosina Pierotti Professor in Italian Literature, Emeritus, in a eulogy.

Two books by Apostolidès on monarchical power in 17th-century France were “field-defining works that remain required reading in early modern French studies,” Harrison wrote. Those books, The Machine King (Minuit, 1981) and The Sacrificed Prince (Minuit, 1985), consider the intersection of the arts and reign of Louis XIV.

“He was one of the pillars of the French and Italian department at Stanford,” wrote Jean-Pierre Dupuy, a professor in the department, in a eulogy for his longtime colleague.

Psychology and theater

Apostolidès was born in Saint-Bonnet-Tronçais to Paul and Geneviève Apostolidès in Nazi-occupied France in 1943. He grew up in Troyes, a city on the Seine about 90 miles southeast of Paris.

As a teenager, he became enamored with theater and devoted himself to acting and directing. He attended a local conservatory before moving to Paris in the early 1960s, where he studied under the actress and director Tania Balachova, who originated the role of Inès in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit.

Although he wrote and directed plays throughout his life, Apostolidès turned his attention to the study of psychology in the mid-1960s.

He earned a licence (the equivalent to a bachelor’s degree) and a master’s degree in psychology in 1968 and 1969, respectively, from the University of Paris. In 1972, he graduated with a master’s degree in anthropology from the University of Montreal. The same year, he began graduate study in sociology at the University of Tours, where in 1978 he earned a doctorat d’état—a state doctorate, then the highest academic degree in France.

Between 1969 and 1979, Apostolidès taught psychology at several colleges in Montreal and sociology at the University of Tours. In 1979, he was appointed an assistant professor of French at Stanford. From 1981-1987, he taught French at Harvard, where he earned tenure. He returned to Stanford in 1987 as a professor of French and chair of the Department of French and Italian. In 1990, he was appointed the William H. Bonsall Professor in French.

Heroes, victims, and political extremists

His scholarly work reflects the cross-pollination of his interests in psychology, anthropology, and the arts.

In his book Heroism and victimization: A history of sensibility (Exils, 2003), Apostolidès investigates how a culture of heroism, inherited from the Romans and barbarians, and a culture of victimization, inherited from the Judeo-Christian tradition, both have contributed to Western mores but also conflicted with each other. Since World War II, Apostolidès argues, the culture of heroism, defined by violence, domination, and accomplishment, has largely been in retreat, whereas the culture of victimization, defined by pity, mutual respect, and self-renunciation, has been ascendant.

In books on Tintin, Apostolidès offers psychoanalytical and anthropological interpretations of Hergé’s famous cartoons about the boy hero. In Cyrano: Who was everything and who was nothing (Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2006), he provides a literary and political analysis of Edmond Rostand’s play Cyrano de Bergerac.

Apostolidès also was fascinated by political extremists such as Guy Debord, a founder of the Situationist International, and the anti-technologist Ted Kaczynski, known as the Unabomber, who briefly corresponded with Apostolidès from prison. In 1996, Apostolidès wrote a book, The Unabomber Affair (Du Rocher), about the American terrorist, whose manifesto he also translated into French.

Apostolidès wrote many other books, book chapters, and essays. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1987.

‘A true freethinker’

In addition to his scholarship, perhaps his most significant contribution to the Stanford community was his work with students on campus theater productions. He directed or co-directed more than a dozen plays at Stanford, including Sartre’s No Exit; The Maids by Jean Genet; George Dandin by Molière; and The Hacienda Must Be Built, a play that he wrote.

Students flocked to Apostolidès’ film course, Images of Women in French Cinema, in which he expounded on a field he developed and called “iconomy”—the study of images and how they affect people’s lives.

“He was a true freethinker … who provocatively critiqued social and institutional norms,” said Christy Pichichero, a former student of Apostolidès’ who is now an associate professor of French and history at George Mason University and a Stanford Humanities Center fellow. “He brought something entirely unique and irreplaceable to the Stanford community.”

When asked about his diversity of interests in a 2010 interview with Post-Scriptum, a journal published by the University of Montreal, Apostolidès responded: “Peut-être l’unité de mon travail ne sera-t-elle perceptible qu’après ma mort.” (“Perhaps the unity of my work will only be perceptible after my death.”)

He is survived by his wife, Danielle Trudeau, and his son, Pierre Apostolides.