Latino mental health is affected by immigration controversies, study finds

From 2011 to 2018, psychological distress rose among Latino citizens and noncitizens in response to national immigration enforcement efforts and public debate.

It’s not hard to imagine that undocumented immigrants might experience anxiety when they see immigration enforcement efforts intensify or public debates on immigration turn sensational. Now a new study has found that the public tug-of-war over immigration can have an even broader effect, harming the mental health of Latino groups in the United States, including native-born citizens.

The new research, published Feb. 20 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, measured feelings of anxiety and depression in Latinos who were noncitizens, naturalized citizens, and U.S.-born citizens. The researchers charted the participants' responses to monthly surveys against shifts in immigration policy, enforcement, and public interest to gain insight into the effects these had on Latino mental health.

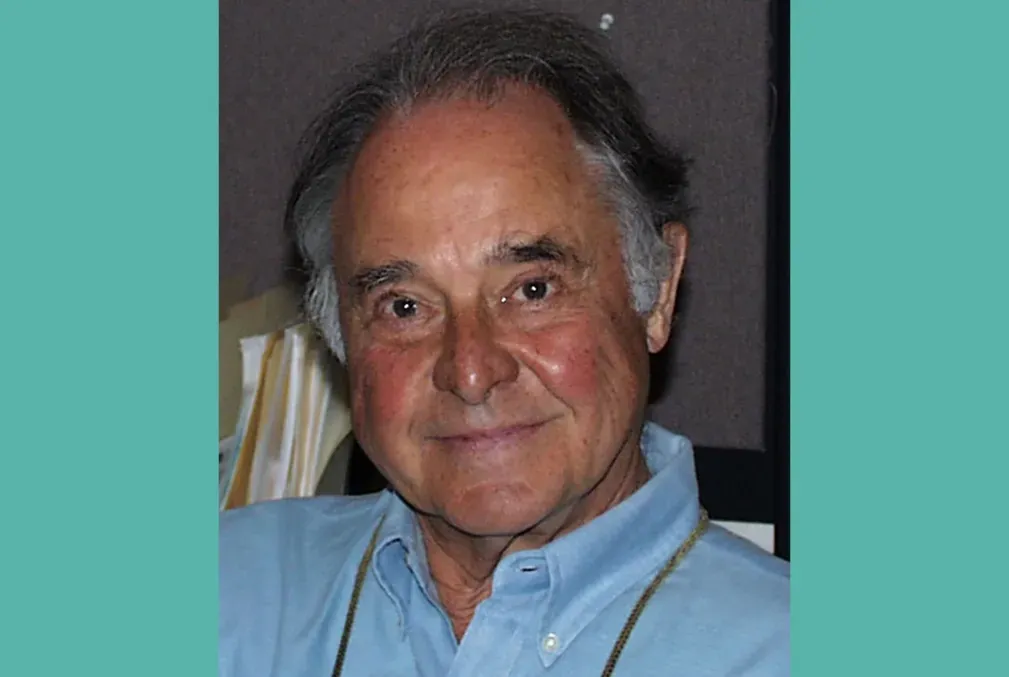

“As a group, Latinos are racialized by public policy, by the enforcement of public policy, and by the United States’ political rhetoric,” said Asad L. Asad, assistant professor of sociology in Stanford's School of Humanities and Sciences and senior author on the paper. “Latinos—who are thought of as undocumented or otherwise ‘illegal’ in the United States—feel threatened by deportation, even when they are citizens and presumably immune to it.”

The study shows that foreign-born Latinos living in the United States—including those with U.S. citizenship—reported having more anxiety and depression at times of increased immigration enforcement from 2011 to 2018. The study measured enforcement by the number of detainer notices sent by federal authorities to police departments around the country asking them to hold noncitizens for possible deportation.

U.S.-born Latino citizens, too, conveyed greater psychological distress in response to immigration issues. Their psychological distress scores were more closely tied to increased public attention to immigration—measured as the volume of related Google searches—than to actual increases in enforcement.

Anxiety and depression levels were measured using the Kessler-6 psychological distress scale, administered regularly through the National Health Interview Survey program to a representative sample of long-term U.S. residents over age 18. Higher scores on the questionnaire indicate greater psychological distress, whether from anxiety, depression, or both.

Asad explained the findings: “If you’re a Latino U.S. citizen, maybe your mental health still feels okay when deportations go up nationally because you’re not directly vulnerable to deportation. But that doesn’t make you immune to the larger racist conversation that arises when, for example, some politicians depict Latinos, as an ethnic group, in a negative light,” he said. “You begin to internalize that as you go about your day-to-day life.”

How policy debates affect individual mental health outcomes

Asad’s research and recent book Engage and Evade (Princeton University Press, 2023) focus on how institutional categories, like citizenship, influence people’s mental, physical, economic, and social well-being.

He showed in a previous paper that fear of deportation was trending up among Latino citizens, while remaining high but stable for noncitizens. In this newly published study, Asad and his colleagues set out to understand how a changing political environment can influence mental health.

The researchers initially expected that major immigration-related events—such as the Obama administration’s 2012 announcement of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program or Donald Trump becoming president in 2016 after he campaigned on repealing DACA—would drive depression and anxiety down or up.

“We predicted these big events would have very clear relationships with psychological distress for Latinos, but we found that they didn’t matter as much as we thought they would,” Asad said.

Although Asad and his colleagues did observe more psychological distress among noncitizen Latinos following the 2016 election, they showed that the everyday immigration environment was more closely tied to mental health than marquee events were. By quantifying the overall immigration enforcement environment each month, the researchers shed light on how the threat of deportation negatively impacts individuals, even when they are not at risk of deportation.

“Our work shows that a deportation-focused approach is psychologically damaging to noncitizens and even to U.S. citizens,” Asad said.

An age of anxiety

The research does not suggest that upticks in anxiety and depression were exclusively Latino or immigration-related problems. Accounts abound of rising anxiety, with blame placed on everything from technology and climate change to political polarization, and Asad and his colleagues acknowledge this general trend in their paper.

“We are very much living in an age of anxiety,” Asad said.

The research showed that psychological distress grew from 2011 to 2018 among Latinos overall and among non-Hispanic White and Black populations born in the United States. The researchers considered these latter populations as comparison groups “neither vulnerable to nor targeted for deportation.” Rising psychological distress in the comparison groups did not align with increased immigration enforcement or public debate as it did in the Latino groups.

Nor did events, including the 2016 election, correspond to a significant uptick in psychological distress among the non-Latino groups.

“It’s not just a national context in which everyone’s anxiety is going up that accounts for our results,” Asad said. “Deportation threat is one additional thing that Latinos are dealing with that U.S.-born White and Black people are not.”

Acknowledgements

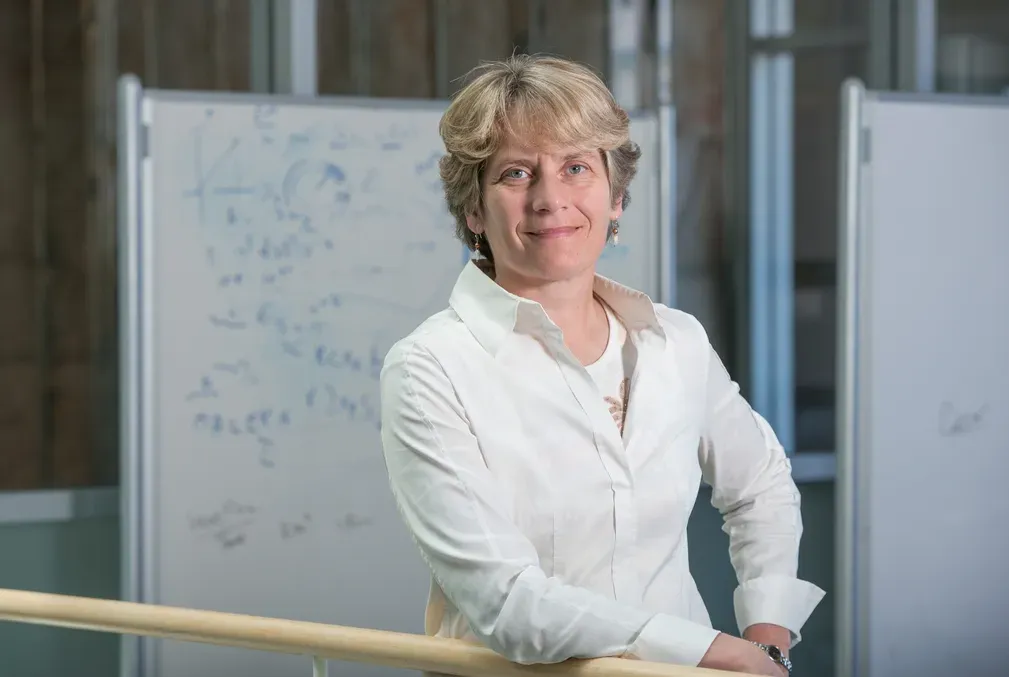

Additional co-authors include Amy L. Johnson, who received a doctorate in sociology from Stanford in 2023, and now is at Lehigh University; Christopher Levesque of Kenyon College; and Neil Lewis Jr. of Cornell University.

Media contact: Holly Alyssa MacCormick, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: hollymac [at] stanford [dot] edu (hollymac[at]stanford[dot]edu)