Survival is success in Mexico City’s underground rehab centers

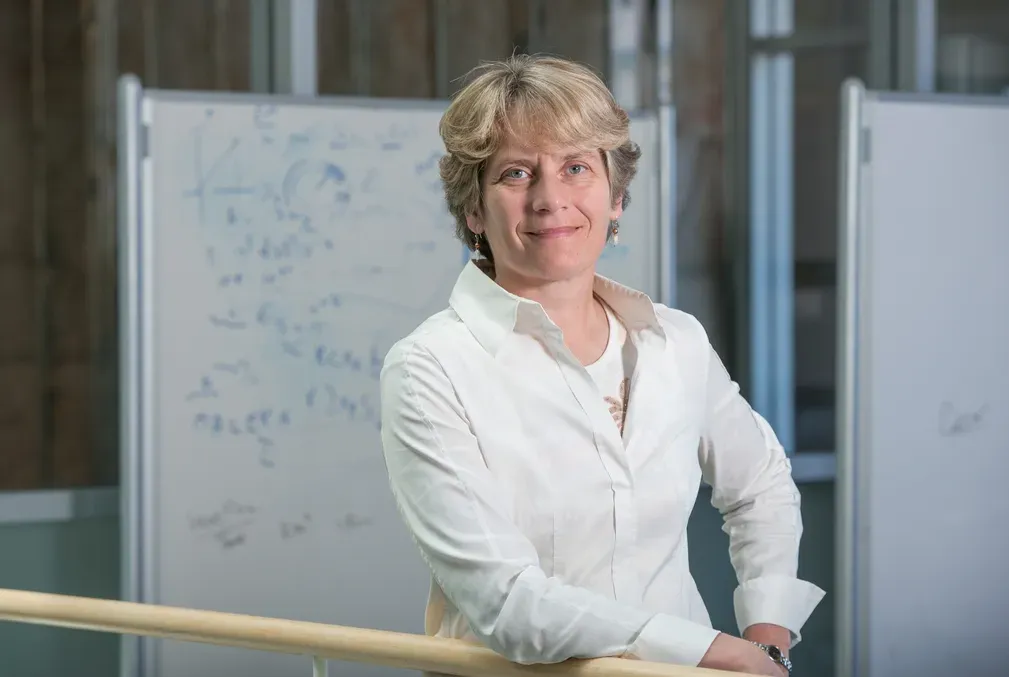

A troubling new type of residential treatment program, described firsthand by Stanford anthropologist Angela Garcia, has emerged to help Mexico City’s poor survive unremitting drug violence.

What would drive somebody to pay for their loved one to be beaten, kidnapped, and held for months or years in an underground drug rehabilitation center located in a single-family apartment, as is commonly happening in Mexico City and, increasingly, the United States?

This question motivates a new book by Angela Garcia, associate professor of anthropology in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. Garcia conducted more than 10 years of research in Mexico City to understand these unsettling drug rehabilitation centers, known as anexos, for her book The Way That Leads Among the Lost: Life, Death, and Hope in Mexico City’s Anexos (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024).

Garcia’s anthropological ethnography, sprinkled with elements of memoir, draws from the extensive time she spent in anexos (annexes) interacting with the residents who slept, cleaned, exercised, fought, and made mandatory admissions of drug use, sexual abuse, and other forms of trauma. Garcia also spent countless hours with the families who paid for residents to be confined.

Anexos provide some 90% of residential addiction treatment for low-income Mexicans, according to the book. Many of their residents are recovering from addiction, but just as many are not. Some have mental illnesses their families can’t handle, and many, if not most, are lying low after inadvertently becoming targets for criminal and neighborhood violence. Anexos offer treatment from self-appointed leaders—generally alumni of similar programs—that consists chiefly of enforced sobriety and shared testimonials. Corporal punishment and slim rations are the norm; physical and psychological abuse are not uncommon.

There’s no evidence this approach effectively treats addiction, but anexos keep residents alive while they’re there.

“Anexos are in many ways very troubling, but at the same time they are lifesaving,” Garcia said. “It’s that tension between care and violence that has always interested me.”

Drugs as a symptom of wider disease

As she documents the effects of U.S. economic, drug, and immigration policies on the Mexican drug economy, Garcia depicts the United States and Mexico in a dysfunctional embrace that has squeezed disadvantaged Mexicans to a point where they need and accept anexos.

“I went into this world of addiction treatment thinking I would better understand addiction,” Garcia said. “But ultimately what I came to understand was that anexos were about more than treating addiction. They were really refuges from the drug war.”

Anexos took off in Mexico City in the mid-1990s, just as the North American Free Trade Agreement shocked the Mexican labor market. Around this time, the country’s long-ruling political party lost its stronghold, setting off territorial disputes among the cartels with whom the party had pragmatic agreements.

The rituals common in anexos also echo the culture of drug violence: “Anexos occupied a crucial position along a continuum of violence, especially since many of their practices—kidnappings, physical discipline, verbal abuse, forced confessions—were shaped by the war that existed beyond their walls,” Garcia writes in the book.

The Mexican government and media use these similarities to write off anexos as hiding places for narco-traffickers, according to the book. But in the experiences Garcia documents, anexos are primarily hideouts where mothers stash their teenagers “to protect them from the violence proliferating in their neighborhoods.” The Mexican government has mixed inadequacy and corruption in its response to violence.

Anexos are crossing the border with the communities they most often serve. Growing numbers are cropping up in U.S. cities with significant Mexican populations; by Garcia’s count, there are more than two dozen anexos in the Bay Area. Unlike their Mexican counterparts, residents of U.S. anexos generally choose to live there and pay their own way by working a regular job. Sobriety-focused communal living, public confessions, and corporal punishment link anexos on both sides of the border.

“The war in Mexico reaches deep into the United States, where it is characterized by drug seizures, overdose statistics, and refugees fleeing unremitting violence,” Garcia writes. “The spread of anexos in the United States keeps pace with the worsening conditions in Mexico.”

Entwining ethnography and memoir

The Way That Leads Among the Lost is, loosely, a companion piece to Garcia’s earlier book, The Pastoral Clinic: Addiction and Dispossession Along the Rio Grande (University of California Press, 2010), which won the Victor Turner Prize from the Society for Humanistic Anthropology for best ethnographic writing. The Pastoral Clinic maps how opioid addiction took hold among rural Latinos in New Mexico—a community from which Garcia hails—as they lost long-held lands and traditions.

Addiction and family separation have a particular appeal for Garcia because she has lived them, as the reader learns in short, interspersed episodes of memoir in The Way That Leads Among the Lost.

Garcia’s family began to disintegrate when she was in her teens. Abandoned first by her mother and then by her father, Garcia wound up living in youth hostels before enrolling in community college, from which she later transferred to the University of California, Berkeley. The hostels, she observes, resembled anexos: intimate and impersonal, cruel and kind, and shaped by drug addiction.

Garcia chose to foreground her lived connection to the subject matter of The Way That Leads Among the Lost “because my experience shaped not only the topic of my inquiry but also how I understand it,” she said.

Anthropology originally positioned itself as an objective social science, but many practitioners have concluded that they can’t study human cultures through interactions with them without also revealing much about themselves. Garcia leans into this more humanistic approach to the discipline.

“I think anthropology’s commitment to long-term up-close participatory research provides a very different kind of understanding of the social and political issues that social scientists are often interested in,” she said. “The genre of ethnography enables anthropologists to provide detailed understandings of very complex social environments and phenomena.”

Addiction reveals itself to be a complex social phenomenon in both of Garcia’s books.

“There are no easy answers to addiction,” she said. “I see my role as someone who generates questions that can help guide new lines of inquiry. I try to expand our understanding without providing easy answers. That’s always a little frustrating for people—and sometimes it's frustrating for me, as someone whose own life has been so marked by this issue.”

Acknowledgement

An early phase of Garcia’s work was supported by a seed grant from the Stanford Institute for Research in the Social Sciences.