Exotic quantum state of matter visualized for the first time

Thanks to a new microwave-based imaging method they developed, researchers have successfully observed a material exhibiting intriguingly fractionalized electric charges on its edges, ushering in new physics and potential applications

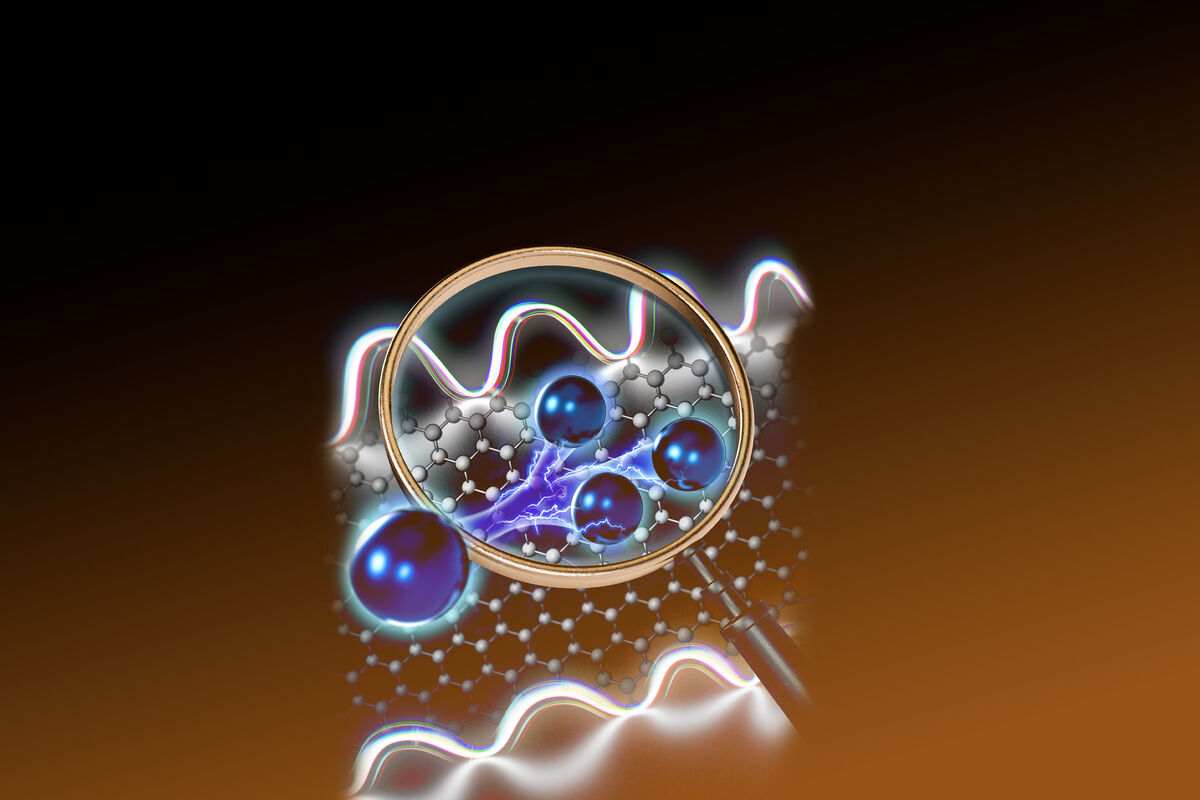

For the first time, an exotic condition of matter known as a fractional quantum Hall state has been directly visualized, thanks to work led by Stanford physicists. The findings could provide new insights into fundamental physics as well as open the door to innovative quantum computers with low error rates.

Going back decades, scientists have wanted to visualize the fractional quantum Hall state, where ultrathin layers of certain materials exhibit unusual electrical properties. For these quantum effects to kick in, however, materials must be held at ultralow temperatures in strong magnetic fields. Such extreme conditions have long challenged attempts to directly observe the fragile quantum phenomena in action.

The Stanford researchers and colleagues got around this obstacle by developing a new method that does not disturb the material and can record its behavior in high spatial resolution. The approach revealed the material’s inner bulk acting like an insulator—meaning electrical current cannot flow through it—while current freely moved around the material’s edges in an exact manner.

Overall, the results, published Nov. 20 in Nature, have demonstrated a way for researchers to deeply examine the intriguing bulk–edge interactions, moving physics forward and enabling potential new applications.

“This paper presents the successful development of a novel measurement technique that makes imaging of fractional quantum Hall states possible; it’s a groundbreaking step in the study of quantum matter,” said study senior author Zhi-Xun Shen, the Paul Pigott Professor in Physical Sciences and professor of physics and applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

“It has long been a challenge to see what the bulk and edge look like in this state,” said study co-lead author Zhurun “Judy” Ji, who was a postdoctoral scholar in Shen’s lab during the research. “As the phrase goes, ‘seeing is believing,’ and now we can really see and hope to understand what’s going on.”

Ji conducted the research in the H&S Departments of Physics and Applied Physics as part of the Stanford Science Fellows Program, which brings postdoctoral scholars from around the world to Stanford for opportunities to work on interdisciplinary topics.

“I feel fortunate to be surrounded by amazing people from different fields who believe in the superpower of community and have provided tremendous support for this project,” Ji said of her experience in the program.

A new way to visualize exotic states of matter

For the study, the Stanford researchers and colleagues worked with a material consisting of two atom-thin layers of molybdenum ditelluride, synthesized by collaborators at the University of Washington. The researchers stacked these semiconductor layers with a slight twist angle between them. The combination of the material and the stacking configuration caused electrons to align in a certain way and generate a special curvature that serves as an internal magnetic field. Thus, an external magnetic field was not needed, and this made precision measurements easier to obtain. The name scientists have given to a material exhibiting this version of the fractional quantum Hall effect is fractional Chern insulator.

To then probe the delicate arrangement of matter in high resolution, Ji and colleagues devised a new version of a technique called microwave impedance microscopy, or MIM. The method sends microwave light—like that in a microwave oven—onto a material sample through a metallic tip. Critically, the tip never makes direct physical contact with the sample, which would upset its fragile quantum state. With standard MIM, though, microwaves do not readily pass through a sample because they are impeded by the electrical gate on the sample that supplies the voltage to induce a quantum state. The researchers got around this issue by using a semiconducting gate made of monolayer tungsten disulfide. When energized by light, this gate becomes transparent to microwaves, thus letting researchers peer deep into the sample’s inner bulk.

“Our technique allows measurements on more sophisticated quantum devices that have intricate structures,” Ji said.

Divining the details

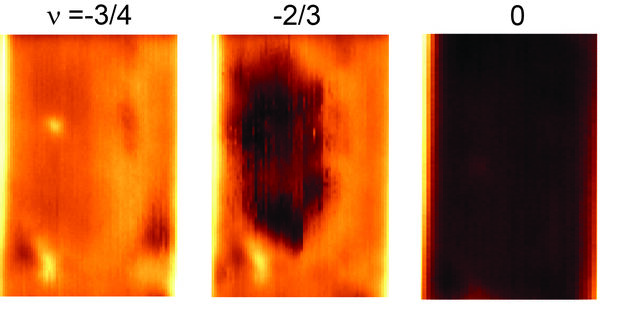

With its MIM method, the research team achieved a spatial resolution of approximately 100 nanometers, or billionths of a meter—on the order of a thousand times thinner than a human hair. At such small scales, the team was able to observe conductivity on the edges of the material coaxed into a fractional Chern insulator state. Interestingly, due to complex physical interactions between electrons—particles that convey electric charge—in the material’s insulating bulk and its conducting edges, the edge electrons carried “fractional” charges (hence the quantum state’s name). This fraction, which equals two-thirds or three-fifths of a usual full electric charge, satisfyingly agrees with theoretical predictions.

Per the new observations, understanding of these materials in such a state has increased substantially. “The measurement results showed the exact nature of the fractional Chern insulators: The bulk of the material is insulating, while the edges are conductive,” Shen said. “This confirms a key theoretical quantum concept proposed a long time ago known as bulk–edge correspondence.”

Ji added that the insights gained about the material edges have allowed researchers to confirm specific theoretical models, and this is just the beginning of what might be possible. “With our novel observation technique, we’re now able to start exploring new quantum phenomena that had been out of reach,” she said.

Building on the findings could lead to developments in quantum information science. One component of this field, quantum computing, has gained much attention in recent years. Quantum computers operate differently than classical computers by harnessing quantum mechanical phenomena to handle certain kinds of calculations with breathtaking efficiency. Even today’s most cutting-edge quantum computers, however, are significantly error prone because even tiny perturbations can scramble the delicate quantum states they employ. Quantum computers based on the material and physical principles demonstrated in the study, known as topological quantum computers, could prove more robust and dependable.

“Some of these states may end up serving as key components for future topological quantum computing,” Ji said.

For now, the team will work to explore, understand, and control the novel quantum states. “One never knows what surprises nature has in store,” Shen said.

Acknowledgments

Shen is also a member of the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford. Ji is currently a Panofsky Fellow at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and will join the faculty of MIT next year.

An additional Stanford co-author is Mark Barber, a physical science research scientist in the Geballe Laboratory for Advanced Materials. Additional co-authors include Heonjoon Park, Chaowei Hu, Jiun-Haw Chu and Xiaodong Xu from the University of Washington and Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi from the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan.

The work at Stanford received major funding from the U.S. Department of Energy and the Stanford Science Fellows program.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Media contact: Marijane Leonard, School of Humanities and Sciences marijane [dot] leonard [at] stanford [dot] edu (marijane[dot]leonard[at]stanford[dot]edu)