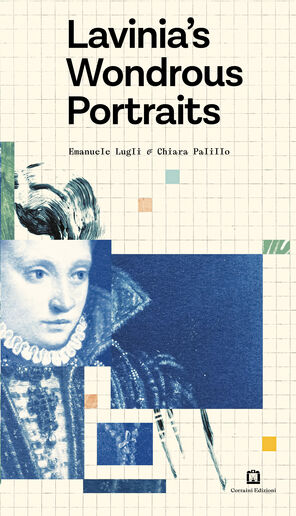

Art history professor’s new book brings overlooked female painter to young audiences

With Lavinia’s Wondrous Portraits, Stanford’s Emanuele Lugli shows Renaissance masterpieces through an 8-year-old’s eyes.

Many professors understandably create work for an audience of their peers and students. For Emanuele Lugli, associate professor in the Department of Art and Art History in the School of Humanities and Sciences, his latest book has a different readership in mind: children.

That book, Lavinia’s Wondrous Portraits, was published this spring by the Italian imprint Corraini Edizioni, and it centers on the life and work of 16th-century Renaissance artist Lavinia Fontana, known for her portrait work. The story is told through the eyes of an 8-year-old girl puzzled by the fact that her older sister is preparing to sit for a portrait by Maestra Lavinia, as the painter is called in the book, and the girl comes to wonder just what a portrait is for, anyway. As the book answers that question, it encourages young readers to ponder other ones, such as how to look at art and what its purpose is in our lives.

The book, which was named one of the 100 outstanding books of 2025 by the picture book platform dPICTUS, has recently become available in the U.S., and it will soon be the subject of an exhibition at the Bowes Art & Architecture Library at Stanford’s McMurtry Building. The show will feature cutouts, original watercolors, and other materials used by the book’s illustrator, Chiara Palillo, along with the books that inspired Lugli in writing the text. It will run Oct. 6 – Dec. 12, with a reception at 4 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 16 during Reunion Homecoming.

But for Lugli, the greatest honor is the book’s resonance with his test audience — his nieces and nephews.

Here, Lugli, who has recently become director of Stanford Public Humanities, shares how he applied his academic research and skills to children’s publishing.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: Where did the idea for doing a children's book about Lavinia Fontana come from?

Answer: I teach the Italian Renaissance, and I talk about women artists and try to showcase their work. But unless you have a PhD, you don't know about these phenomenal, extremely successful artists who have been left on the margin of art history. I thought, “You have to reach people when they’re young. We need a children's book.”

I'm also one of the victims of the way art history was taught. I did not know about Lavinia Fontana until after my PhD. So I started doing my homework and became a little bit of an expert.

She's really the first professional woman artist. She didn't join a court of royals or work for an aristocrat. She had her own workshop and commissions, which is quite extraordinary. She's a product of a cultural shift that happened across Europe in the 16th century, when women start developing a voice and going against authorities of all kinds. She's the one who breaks the glass ceiling for the arts.

Question: The book doesn’t take the typical path of a biography. Instead, it’s told from a little girl’s point of view. Why?

Answer: I wanted to provide a story that would immerse readers in some of the questions— not just about those related to her gender, but also about what artists do in the first place.

So I thought it could be interesting if the protagonist is actually an avatar for the readers. She is someone who not only doesn't understand why a portrait is needed, but also doesn't understand why you want to look beautiful in a portrait.

Question: How did you capture the day-to-day reality of the time period?

Answer: Everything in the book comes from documents of the time and real-life scenarios. For example, the main character’s name is Camilla. In 16th-century literature, Camilla is always a female warrior, and the character has the curiosity and entrepreneurial spirit of a warrior.

Some lines of dialogue come from treatises of the time. All the words of a friar that Camilla imagines are taken from a sermon given in the 16th century.

I wanted to expose children to the texture of life at the time so they may understand it. By putting these pieces of the puzzle together, I ended up coming up with a story.

Question: This book took three years to put together, despite being only 48 pages. What took so long?

Answer: I never thought that writing a children's book would have been much harder than writing academic monographs or exhibition catalogs.

With children’s books, you have to be very attentive when finessing the text. For instance, one of the characters used the word strange when describing a girl that she believes to be a monster. And the publishers told me, “No, strange is a difficult world for a 6-year-old. It means lots of things — negative, maybe positive. Lots of kids find themselves strange. So maybe we should avoid that.”

Question: Did you test the book with any children you know?

Answer: Oh, definitely. The book must have gone through, I'm not joking, 30 drafts. I first sent it to a couple of my nieces and family members, and their feedback was very blunt. I went back to the drawing board.

Also, I wrote this while I was on sabbatical in New York and volunteering at Read 718, helping teach the children of immigrants how to read English. I saw what they struggled with and what they found particularly interesting. That was eye opening.

Question: You offer a special thanks to Stanford at the end of the book. Why?

Answer: Stanford helped in many ways. First, I spoke to my colleagues in my department, who encouraged me and gave important advice on first drafts. My department also gave me some funds that basically paid for the illustrator.

And Stanford has this amazing program called the Public Humanities, and it helped in so many ways.

I'm sure there are many professors of art history who would be completely discouraged from writing a children’s book. My colleagues did the opposite. They were like, “Go for it. It's amazing. This is needed.”

The book is available in English, Italian, and French. It is for sale in the U.S. online and in store at Libreria Pino in San Francisco (Italian and English versions) and on Amazon (English version).