Historian chronicles one of the French Revolution’s most notorious figures

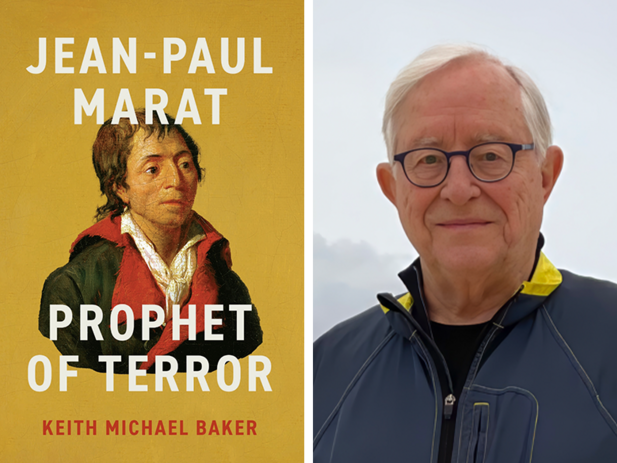

In a new biography, Stanford Professor of History, Emeritus, Keith Baker traces the path of Jean-Paul Marat from doctor to revolutionary who was held responsible for the massacre of more than a thousand prisoners during the French Revolution.

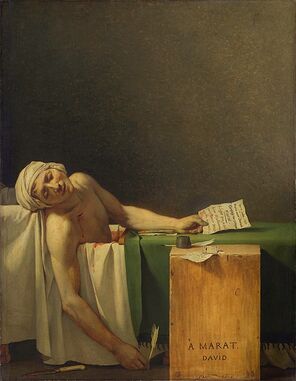

Jean-Paul Marat, who advocated for the execution of the “enemies” of the French Revolution, may be most well known today for his own death. The portrait of his murder in a bathtub, painted with the intent to make him a martyr, remains an icon of art in the service of political zealotry.

Now a new biography by Keith Baker, the J.E. Wallace Sterling Professor in Humanities, Emeritus, in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, examines this era of political violence through the life and radicalization of Marat. Once an ambitious doctor and in search of scientific glory, Marat later turned to writing incendiary pamphlets and is often credited for inciting the September Massacres of 1792, which led to the death of more than a thousand political prisoners. Even though he was beset by a debilitating skin disease, Marat continued to write, even from the bathtub where he took long medicinal baths to ease the condition.

In this excerpt from Jean-Paul Marat: Prophet of Terror (The University of Chicago Press), Baker recounts how Marat’s illness came and went in parallel with his political fervor right up until he met his end at the hands of another revolutionary, Charlotte Corday.

Excerpted from Jean-Paul Marat: Prophet of Terror. Copyright 2025 by Keith Michael Baker. Used with permission of the publisher, The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.

Marat fell gravely ill toward the end of 1788. Fearing death, he briefly entrusted his friend Breguet with his papers and scientific instruments. The latter were to be conveyed at his demise, in a posthumous act of defiance, to the Academy of Sciences. In later years he saw this bout of illness as symbolizing a passage toward transformation. An open letter he addressed to the president of the revolutionary National Assembly in May 1790 likened his travails under the Old Regime to those of the French nation. The critical engagement in radical politics to which he had been drawn in England had been too dangerous to continue in France, he now claimed. He had turned instead to a career in the sciences—only to encounter persecution by multiple enemies. He saw his own victimization reflecting that of the French nation. Abuses of all kinds had been reaching their height, the people had been growing increasingly wretched, the wealthy had been discovering the expropriation of their fortunes to pay for court excesses, and enlightened minds had been longing for a new order of things. As the French barely escaped annihilation, so did he.

“Long groaning at the ills of my country, I was on my deathbed when a friend, the only one I had wished to witness my final moments, informed me of the calling of the Estates General. This news made a strong impression on me, I experienced a salutary crisis, my courage revived, and the first use I made of it was to give my fellow citizens proof of my devotion. I wrote l’Offrande à la patrie.”

Alerted by Breguet in this telling, Marat wrote his way back to health—as he would eventually write his way to his death. The persecuted scientist was delivered to persecute in his turn, the “apostle and martyr of liberty” was born.

book Launch Event

Thurs., Nov. 20 at 5:30 p.m. at Green Library

Baker will preview the book and then be in conversation with French Professor Dan Edelstein.

Get more information.

In January 1793, again under particular fire for his radical views, Marat once more recounted the story of his deliverance from the injustices of the Old Regime. This time, he emphasized the “ten years of disgraceful persecution” he had received from the likes of “the d’Alemberts, the Caritats [de Condorcet], the Le Roys, the Meuniers, the Lalandes, the Laplaces, the Monges, the Cousins, the Lavoisiers,” those charlatans of the Academy of Sciences who wanted to remain at the top of the heap, orchestrating the trumpets of renown.

“I was groaning for five years under this cowardly oppression when the revolution was announced by the convocation of the Estates General,” he declared. “I soon saw the way things were going and I began to breathe again in the hope of seeing humanity finally avenged, of helping break its chains, and of achieving my place. This was still only a fine dream about to vanish; a cruel illness threatened that I would finish it in the tomb. Not wishing to end my life without doing something for the cause of liberty, I composed l’Offrande à la patrie on a bed of pain. This little work had much success . . . the pleasure I felt was the principal cause of my recovery. Restored to life, I only occupied myself thereafter with the means of serving the cause of liberty.”

Thus “restored to life,” Marat seized a moment of opportunity for yet another career. He became a political pamphleteer and then a revolutionary journalist. His very existence would henceforth be utterly bound up with the Revolution. It is striking that illness, recovery, and the passage to political resurrection were so closely related in his accounts of this rebirth.

Thanks to Jacques-Louis David’s painting immortalizing him at the moment of his assassination in his medicinal bath, Marat is remembered as the most dramatically afflicted among the revolutionaries. Though we have no way of ascertaining this, the grave illnesses from which he suffered in 1782 and 1788 may well have sprung from the same underlying condition that would incapacitate him by 1793. We can only guess at its nature, and many retrospective diagnoses have been hazarded. It seems likely that he suffered from some kind of itching, burning, purulent skin disease spreading from the anogenital area. A recent analysis of DNA from a bloodstain on an issue of his journal cast doubt on contemporary diagnoses such as syphilis and leprosy, hypothesizing “a fungal infection (seborrheic dermatitis), possibly superinfected with bacterial opportunistic pathogens.” It could well have been an inflammatory bowel disease or acute celiac disease, or similar chronic condition that can flare up during periods of stress.

The years 1782 and 1788 saw particular despair and frustration of Marat’s hopes for scientific recognition. Months of privation subsequently spent in hiding during the revolutionary period, culminating in exhaustion from intense political engagement, could only have exacerbated the seriousness of his symptoms to the point of forcing his confinement to a curative bath in 1793. He was widely rumored to be again on his deathbed at the time of Charlotte Corday’s fateful visit in July 1793.