Advance could expand immune therapy as a cancer treatment

The development of antibody-lectin chimeras, which started in the lab of Stanford chemist Carolyn Bartozzi, shows promise in blocking the defenses put up by cancer cells and allowing the immune system to attack the diseased cells more effectively.

While immune therapy can cure some cancers, relatively few patients, about 20%, can benefit from it. Now a newly created multifunctional molecule, called an antibody-lectin chimera, or AbLec, has the potential to greatly expand and improve this type of treatment.

AbLecs are made up of an antibody that targets a particular type of cancer tumor and a protein called a lectin that binds to the tumor’s glycans, which are types of sugar molecules. A recent study in the journal Nature Biotechnology shows how glycans found on the surface of cancer cells can prevent immune system cells from killing the cancer. Previous immunotherapy advances have focused on the cancer-specific proteins that block the immune system’s work, so this advance represents a new approach—and has implications for other types of disease treatments as well.

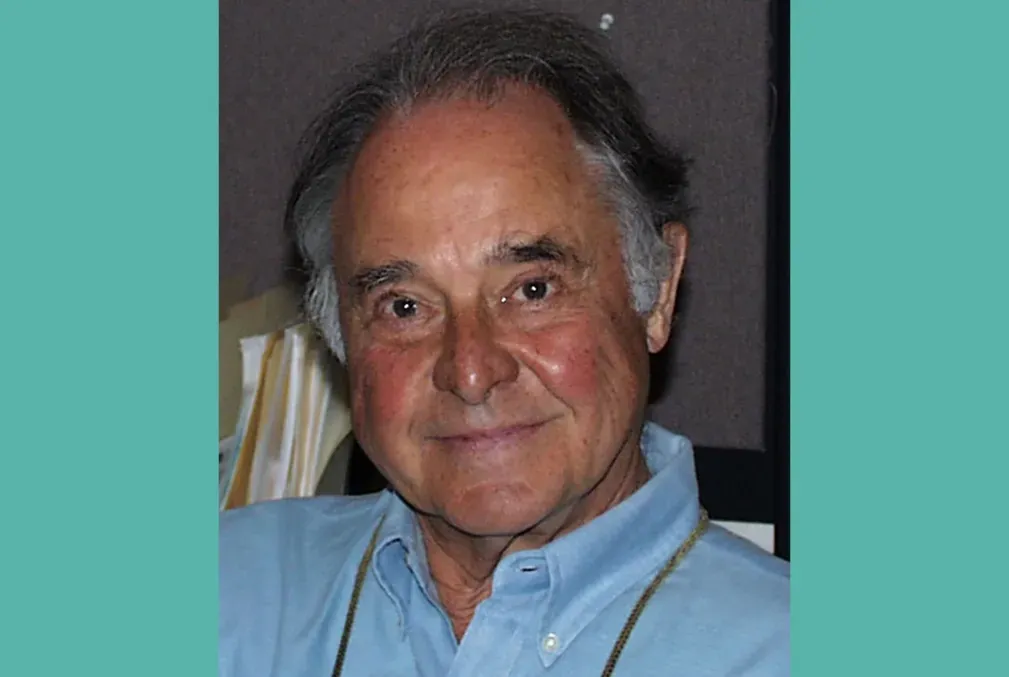

We talked with the study’s senior author, Carolyn Bertozzi, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, about the potential of AbLecs and how Stanford is helping to translate this fundamental science into a potential treatment. Bertozzi is also the Baker Family Director of Sarafan ChEM-H. The study’s lead author, Jessica Stark, an assistant professor of biological engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, initiated the work as a postdoctoral fellow in Bertozzi’s Stanford lab.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: What do you find most exciting about the development of antibody-lectin chimeras? What is the potential here for a new cancer treatment?

Answer: The goal with the AbLec molecules is to make targeted immune therapies that act by a totally different mechanism than previous therapies and that hopefully will work for patients for whom the first generation of immune therapies haven't worked. Unfortunately, that is most patients. A small fraction of patients are cured, and that's amazing, but the field has really struggled to figure out why more people don't respond.

There is also a bigger picture here: Glycans as a class of biological molecules are really important in a lot of biological processes, but they are relatively understudied and underexploited in drug development.

Developing molecules like AbLecs that target that biology has the potential to revolutionize not only the treatment of cancer, but also many other unmet therapeutic needs as well. There's an open playing field to think about the different combinations of targeting antibodies and lectins.

Question: How do AbLecs work to fight cancer?

Answer: There are certain patterns of glycan structures that distinguish cancer cells from healthy cells. The lectin part of AbLec binds specifically to the kinds of glycans found on cancer cells, which can otherwise put immune cells to sleep. It prevents the glycans from interacting with immune cells, allowing the immune system to do its job and attack the cancer cell.

Question: You have been a great proponent of translational science, and this advance is already being developed by a startup company, Valora Therapeutics. How were you able to get AbLecs to this stage?

Answer: The Innovative Medicines Accelerator (IMA) at Stanford allowed us to take this academic project further down the translational path, which made the technology more competitive for outside investments.

Jessica Stark had the idea to combine these two molecules into one. It's not as easy as sticking two Legos together. We needed help because the first time that we made the AbLecs, they weren't very stable, and we weren't able to produce a lot.

That's the place where a lot of academic science is halted because it costs a lot more money and requires different skills to go from doing fundamental science in the laboratory to scaling up and doing large animal studies.

We pitched a proposal to the IMA, and they worked with us to make the AbLec molecule on a larger scale and fix some of the liabilities. That gave us a dataset on which we launched the company.

Very often, you end up with this so-called “valley of death,” where the science comes to a point where it can't progress toward a medicine. The venture capital investors are often on the other side of that big canyon. We want to narrow that gap so we can leap over it from the academic world to the investment and startup worlds. And that's what the IMA did. It was a bridge across that canyon.

To read more about this advance, see the press release from MIT.

Acknowledgments

Melissa A. Gray, a Stanford postdoctoral fellow in chemistry, is also a co-author on this study.

Additional collaborators include researchers affiliated with MIT; The Rockefeller University; Christian Albrechts University Kiel and University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany; University of California, Santa Barbara; University of Washington; University of Minnesota; Budapest University of Technology and Economics; and University of British Columbia.

The research received support from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface, a Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Steven A. Rosenberg Scholar Award, a V Foundation V Scholar Grant, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, a Merck Discovery Biologics SEEDS grant, the American Cancer Society, the National Science Foundation, and a Sarafan ChEM-H Postdocs at the Interface seed grant. For the full list and details of funding support and co-authors, please see the study.

Media contact:

Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, 510-872-0340, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)