Four things to know about ethnic studies in California high schools

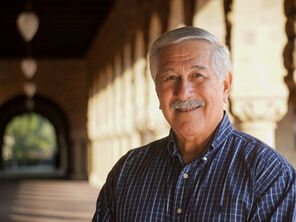

The state mandated that high school students take ethnic studies before they graduate, but many districts are not prepared to offer it. Stanford historian Al Camarillo, a pioneer in the study of race and ethnicity, still believes the effort has tremendous potential.

This fall was supposed to see the start of mandated ethnic studies courses in every high school across California, marking a first for not only the state, but also the nation.

By all accounts, the rollout has been anything but smooth. Funding problems and significant pushback, both from politicians and some parents, have stymied the effort, but Stanford historian Al Camarillo still sees a lot of reasons to persevere.

“What gives me hope is that when I talk to parents and students, they say that exposure to this curriculum has opened their eyes,” said Camarillo, the Leon Sloss Jr. Memorial Professor, Emeritus, in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences. “It has allowed them to understand others and reach out to connect with people they maybe wouldn’t have otherwise.”

Camarillo himself is known for firsts: He was the first person to earn a doctorate in U.S. history with a focus on people of Mexican origin, and he is considered to be one of the founders of the field of Chicano and Mexican American studies. At Stanford, he was the founding director of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity in 1996.

Recently, Camarillo and Veronica Terriquez, director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, conducted a survey of teacher preparation programs for ethnic studies, finding both good and bad news. As districts struggle to implement the mandate, Camarillo said that there are a few things people should know about teaching ethnic studies in high schools:

The mandate is new, but teaching ethnic studies in California K-12 schools is not.

Many districts throughout California have offered ethnic studies courses in their schools for decades. That includes San Francisco, which has offered ethnic studies since 2010, and Los Angeles, which mandated the subject in 2018 but had optional classes as early as the 1990s.

What is fundamentally new is the law that all high schools provide this coursework. The California legislature passed it in 2021, stipulating that at least a one-semester course be offered starting in the 2025-26 academic year. At a minimum, the curriculum would cover the history and culture of the four major ethnic and racial minority groups in California: African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans. Schools would have the option of adding other groups, such as the Armenian or Hmong populations, that might be particularly relevant to their areas.

The lack of state funding is holding back implementation.

While the legislation mandating ethnic studies classes came with an initial $50 million in funding, lawmakers have not funded new curriculum development. Without that support, many schools have been left trying to figure out how, or even if, to offer the coursework.

“It's a way for some districts not to implement ethnic studies,” Camarillo said. “For those planning to offer it, it’s a real problem to not have the resources to prepare their teachers.”

A majority of the state’s colleges and universities are involved in training teachers, but instruction is uneven.

In the survey of 34 California higher education institutions conducted in 2024, Camarillo and Terriquez found that 77% were offering some type of teacher training in ethnic studies.

However, the type of instruction varies, with about half providing courses and the rest offering workshops, speaker series, and other supplemental learning opportunities. About 64% reported directly collaborating with K-12 districts or schools on ethnic studies curriculum or professional development.

Camarillo was encouraged by the number of higher education institutions that were actively engaged in training teachers to provide ethnic studies but said there is obviously more that needs to be done.

If the problems can be addressed, this is a huge opportunity for California to lead.

There has been national pushback on the idea of ethnic studies in schools, and some states, such as Florida, have banned it. Even in California, there are very vocal critics.

State lawmakers should seriously consider the concerns of parent groups in particular, Camarillo said, as many of them are raising good questions—including how a high school can provide excellent instruction in ethnic studies if it doesn’t have the resources to develop that curriculum.

Overcoming the hurdles would be well worth the effort, Camarillo argues, as helping young people understand those who are different than themselves is critical to building a better society. And there’s no better place to do it than the Golden State.

“California is one of the most diverse societies in our country,” he said. “If we can show progress in creating a diverse democracy, where people can better understand each other and hopefully get along better than they have in the past, that would be enormously encouraging to so many people.”

Media contact:

Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, 510-872-0340, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)