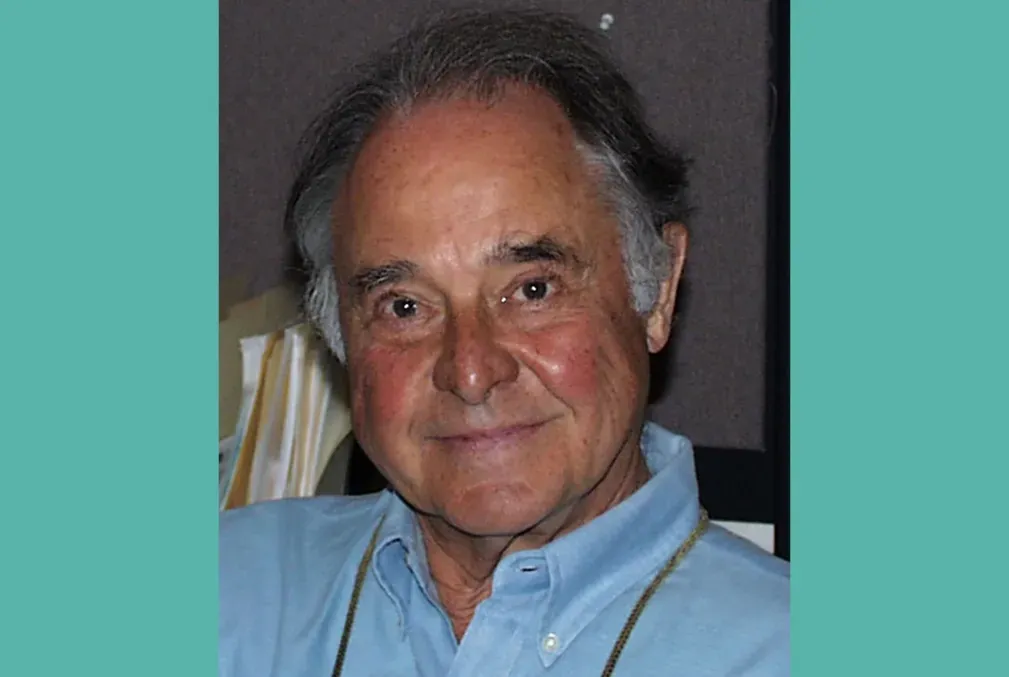

Michael Friedman, who studied the connections between philosophy and science, has died

The esteemed professor and prizewinning Kant specialist was 77.

Michael Friedman, the Suppes Professor of Philosophy of Science, Emeritus, in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, known for studying Immanuel Kant through the lens of the natural sciences, died March 24, 2025. He was 77.

Friedman’s lifework explored how philosophy and science interact. He began by grappling with the philosophy of physics and Einstein’s theory of relativity and then turned his attention to Kant, the 18th-century German philosopher famous for his categorical imperative. Friedman’s novel approach entailed applying the writings of Kant to the study of science itself. Friedman also studied the movement of knowledge in the other direction, investigating how the science of the time influenced Kant’s thinking. Friedman’s work earned him a variety of international prizes, and his connection to Stanford began with a lecture series on Kant in 1999, a year before he joined the faculty.

“Michael was one of the most penetrating philosophical intelligences of our era, and his work has left an indelible mark on our field,” said R. Lanier Anderson, the J.E. Wallace Sterling Professor of the Humanities and professor of philosophy in H&S. “Michael was a philosopher’s philosopher. He was immensely serious about our subject and relentlessly demanding both in the excellence he expected from his interlocutors (and himself!) and in his recognition that knowledge and philosophical understanding are a never-ending journey into an open future.”

An enormous mind and a rigorous thinker

Friedman became a professor at Stanford in 2000 and was named the Frederick P. Rehmus Family Professor of Humanities in 2002, a title he held until 2015 when he became the Suppes Professor of Philosophy of Science. In addition, he served five terms as director of the Patrick Suppes Center for the History and Philosophy of Science between 2004 and 2024, the year he retired from the university.

One career highlight was earning the prestigious Fernando Gil International Prize in Philosophy of Science for his book Kant’s Construction of Nature: A Reading of the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (Cambridge University Press, 2013), which connected Kant’s work to that of Isaac Newton. As Thomas Ryckman, professor of philosophy (teaching), emeritus, in H&S, put it at the time, the work was “a stunning new interpretation of Kant's profoundly deep insights into Newtonian mechanics as well as into its difficult problems with absolute space and absolute motion.”

In addition, Friedman’s 1999 lectures were collected in Dynamics of Reason: The 1999 Kant Lectures at Stanford University (CSLI Publications, 2001), and he edited, translated, or contributed to a number of other books on philosophy and science both during and before his time at Stanford. As a researcher, his honors included a fellowship at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in 2006–07 and the 2008 Humboldt Research Award, which allowed him to do a year of research in Germany.

He also taught a large number of doctoral and postdoctoral students, many of whom contributed to Discourse on a New Method: Reinvigorating the Marriage of History and Philosophy of Science (Open Court, 2010), a collection that also featured a 200-page essay from Friedman himself.

“Of my near contemporaries, Michael is the one from whom I learned the most, on topics where I was an interested onlooker (like the philosophy of physics) and on topics I strove to make my own (like Kantian ethics),” said David Hills, associate professor of philosophy (teaching) in H&S. “Michael’s work was patient and meticulous in its execution and brilliant in its conception. He was humane, funny, affectionate philosophical company—a real Mensch.”

“Michael’s mind was enormous," said Gregory Wong-Taylor, who worked with Friedman for five years as a postdoctoral scholar and is now a Suppes Postdoctoral Research Fellow. “He was intimately familiar with both the history of philosophy and the history of science, even down in its finest details, for a period spanning five centuries. He was also a rigorous logical thinker, and the sharpness of his intellect stood out to everyone who ever spoke with him about anything. These two virtues are brought together in the most fundamental philosophical lesson Michael has left for us: that philosophy and intellectual history are interdependent and that thinking in a philosophically rigorous way requires attention to historical context.”

‘Ice cream, therefore God’

Born in Brookline, Massachusetts, Friedman earned his bachelor of arts from Queens College in 1969 and his doctorate from Princeton University in 1973. He taught at Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Illinois at Chicago before joining Indiana University in 1994. There, he chaired the department of history and philosophy of science from 1995 to 2000, before joining Stanford for the rest of his career.

Much of Friedman’s work was devoted to the life of the mind and its interaction with its physical surroundings. The same could be said for his life—he was a professor, yes, but could often be found rock climbing, and he had a love for the music of Motown.

His love of philosophy, alongside a fondness for wordplay and sweet treats, is evident from an anecdote told by Hills: “He once said his favorite argument for God’s existence was the argument from ice cream. Its very name constitutes a complete statement: Ice cream, therefore God.”

Friedman was preceded in death last year by his wife and philosophical collaborator, Graciela de Pierris, who also taught at Stanford. He is survived by his mother, his sister, her two children, and his three grandnieces.

A memorial service honoring both Friedman and de Pierris will be held Tuesday, June 10 at 4 p.m. on campus. RSVPs are required. Email Linda Fagan (linda [dot] fagan [at] stanford [dot] edu (linda[dot]fagan[at]stanford[dot]edu)) for details.