Novel drug holds potential for treating lung, pancreatic cancers

Research found that the chemical compound was highly effective in a study for reducing lung and pancreatic cancer tumors in mice—and even more effective when combined with another known treatment. The study gives hope for new therapies for the two diseases, which currently have limited treatment options.

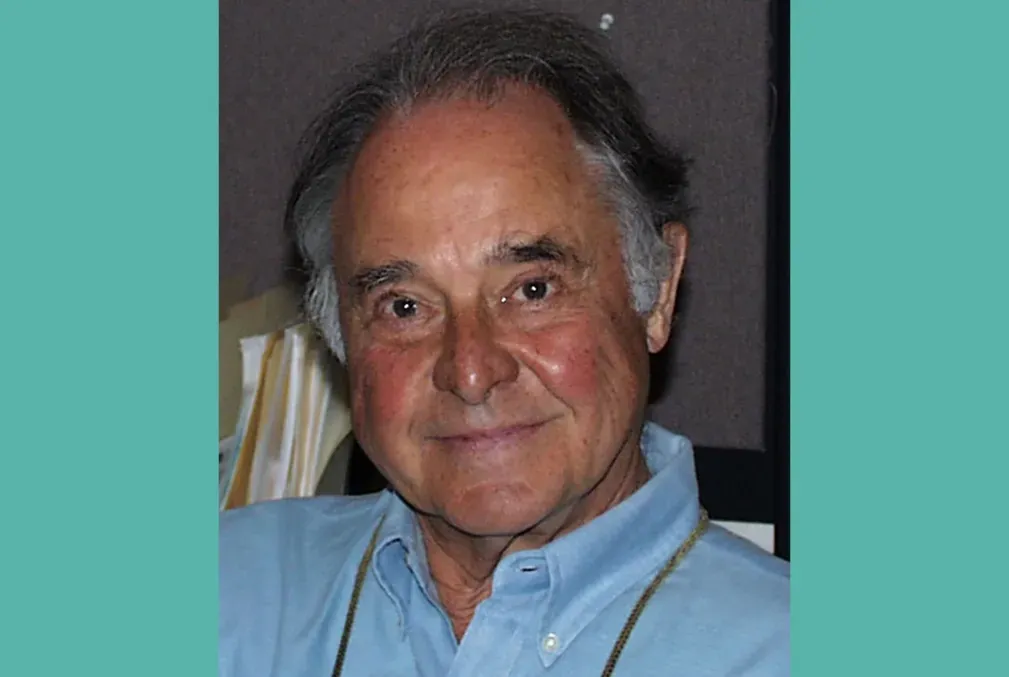

A new drug showed promise as a treatment for lung and pancreatic cancer by blocking cancer-promoting proteins from accessing the DNA of tumor cells in a study led in part by Stanford biologist Or Gozani.

Reporting in the journal Nature, the researchers tested the drug in animal models of the disease, finding it was particularly effective when combined with an existing therapy already in use. While clinical trials are still needed, Gozani is optimistic about its potential to help human patients.

“We’ve characterized a novel drug that shows very promising anti-tumor activity for two very difficult-to-treat cancers,” said Gozani, the Dr. Morris Herzstein Professor and professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences and the study’s lead senior author. “Now that we better understand how it works, we should be able to translate these findings to help patients relatively quickly.”

Gozani also noted that the compound has apparent low toxicity and could be taken orally in pill form—both good properties for a future cancer therapy.

Blocking access to cellular DNA

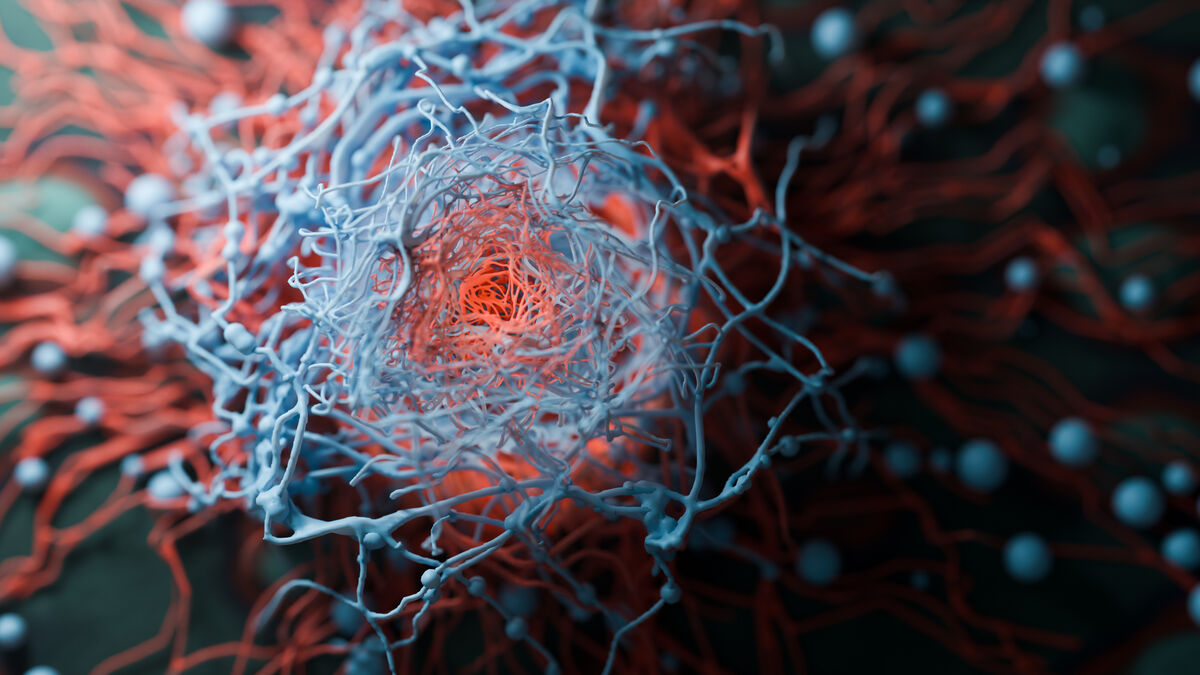

The drug is based on epigenetics, meaning it focuses on the molecular processes that can modify how genes are expressed without changes in the actual DNA. In this case, the researchers found that the compound is a highly potent inhibitor of an enzyme called NSD2, which is more abundant in cancer cells than in normal tissue. Gozani and other scientists have theorized that the excess of this enzyme may be allowing cancer-promoting transcription factors, which are proteins that can regulate genes, abnormal access to DNA. These factors can then drive the process that causes uncontrolled growth of cells—which is a hallmark of cancer.

The drug is also highly selective, targeting just this particular enzyme, which helps lower the potential for unwanted side-effects.

Many scientists have been working for years to find an effective way to inhibit NSD2—including Gozani who has spent nearly two decades studying this enzyme—with the hope that suppressing the access to DNA could work to help cancer patients.

A similar NSD2 inhibitor is now in clinical trials for treating multiple myeloma, a common type of blood cancer that is often driven by NSD2 overexpression.

Seeing the potential to treat other cancers, Gozani and his colleagues characterized potential compounds that are similar in chemical structure to the one in clinical trials. They tested the most effective ones on a range of lung and pancreatic cancer models in mice and with human tumor tissue.

After finding promising therapeutic activity in suppressing tumor growth for the NSD2 inhibitor by itself, the researchers then combined it with an existing therapy that inhibits a protein produced by a gene called KRAS, which is associated with cell growth and division. Activating mutations of this gene are some of the most common drivers across many cancers.

The results of the combined treatments—the inhibitor of NSD2 enzyme and the inhibitor of the KRAS protein—had a dramatic effect on lung and pancreatic tumors in mice, in some cases causing the cancer to disappear entirely.

“There was a massive effect. It was four-times better than each drug alone,” Gozani said. “If these types of results translate from mouse to human, it could mean adding years of life to lung- and pancreatic-cancer patients. It remains to be seen if that can be done, but it’s extremely promising.”

Other Stanford co-authors on this study include biology graduate student Jinho Jeong and a biology postdoctoral scholar, Hanyang Dong, who share first authorship with two other researchers. Biology postdoctoral scholars Moritz Jakab and Rui Dong and School of Medicine postdoctoral scholar Dylan Husmann are also part of the study.

Additional co-authors on this study include researchers from MD Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas, McGill University in Canada, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, and EpiCypher Inc.

This research received funding from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Defense, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, the American Cancer Society, and the Stanford Cancer Institute.

Gozani is a co-scientific founder and stockholder of EpiCypher, Inc., K36 Therapeutics, Inc., and Alternative Bio, Inc. Co-corresponding author Pawel K. Mazur is a consultant and stockholder of Ikena Oncology, Inc. and Alternative bio, Inc. EpiCypher is a commercial developer and supplier of reagents and platforms (e.g., CUTANATM CUT&RUN) used in this study. Co-authors Courtney A. Barnes, Laiba Khan, Liz Marie Albertorio-Sáez, Eva Brill, Vishnu Udayakumar Sunita Kumary, Matthew R. Marunde, Danielle N. Maryanski, Cheryl C. Szany, Bryan J. Venters, Carolina Lin Windham, and Michael-Christopher Keogh are employed by and own shares in EpiCypher. Keogh and Gozani are board members of EpiCypher.

Media contact:

Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, 510-872-0340, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)