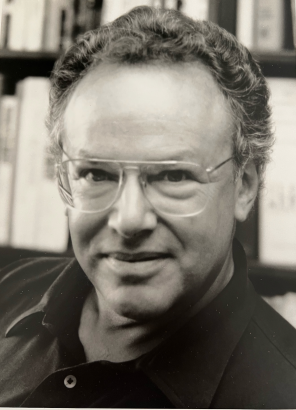

Paul A. David, who made Stanford a leading center for economic history, dies at 87

David conducted influential research on technology diffusion and sought to make the study of economic history more rigorous by promoting a quantitative approach to the field.

Paul A. David, an economic historian at Stanford best known for his research on technological change and how it affects social and economic behavior, died Jan. 23 at his home in Palo Alto. He was 87.

The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, his daughter, Rachel David, said.

A professor emeritus of economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, David led the effort to found the Center for Economic Policy Research, now called the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, and served as a senior fellow there.

He also established Stanford as a prestigious center for economic history, recruiting luminaries such as Ran Abramitzky, Avner Greif, Nathan Rosenberg, and Gavin Wright to the faculty of the Department of Economics. Although the legendary economist Moses Abramovitz laid the groundwork for the university’s reputation in the field, it was this group of scholars who cemented it. Among their notable achievements was advancing the field of new economic history, or cliometrics—the application of economic theory and quantitative tools, such as statistical and mathematical models, to study economic history.

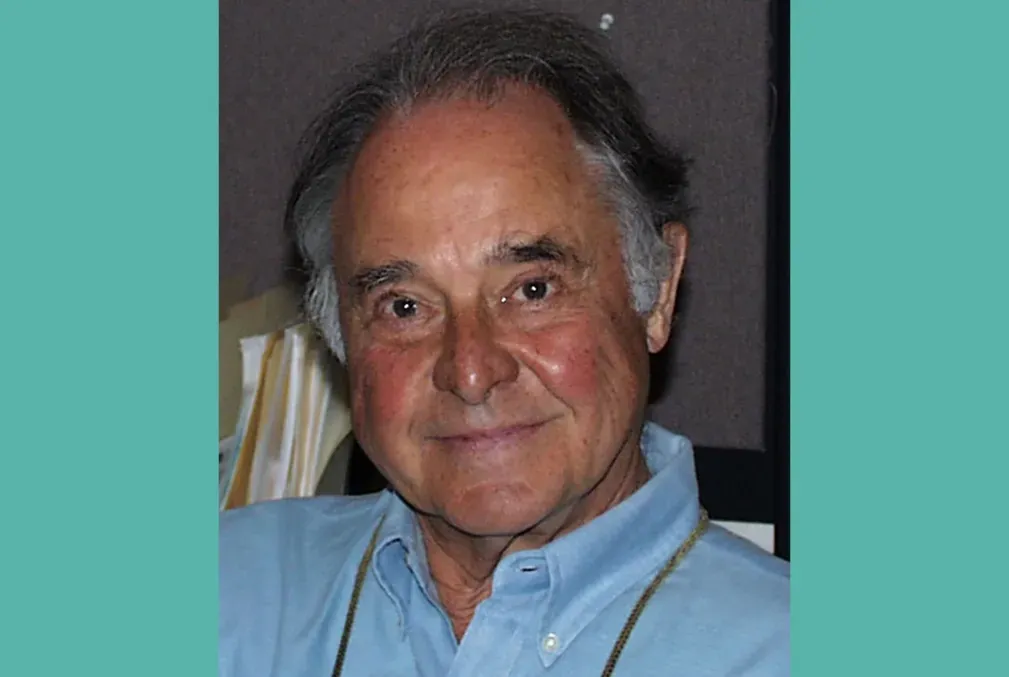

“Paul thought of us as an insurgency,” said Wright, the William Robertson Coe Professor of American Economic History, Emeritus. “The idea was to make economic history more rigorous.”

David believed “historical research should be fundamental to the economics discipline”—in short, that “history matters,” Wright added.

That phrase could easily serve as an epigraph of David’s view of economics. Indeed, it was the title of a collection of essays published as a tribute to his career. “No scholar has more forcefully and influentially argued the case for making economics a truly historical social science—one that, like evolutionary biology, gives past events a central role in understanding the present,” the editors of the volume write in its introduction.

New York native

Paul Allan David was born May 24, 1935, in New York City to Evelyn Levinson and Henry David, a distinguished historian of the American labor movement who taught at Columbia University.

Paul David earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from Harvard University in 1956 and then spent two years studying economic history at the University of Cambridge as a Fulbright scholar. In 1958, he returned to Harvard to pursue a doctorate. He wrote hundreds of pages of a dissertation on the economic history of Chicago but never finished it. In 1961, without a doctorate, he accepted a job offer from Stanford as an assistant professor of economics. He earned tenure in 1966 and became a full professor in 1969.

Scholars close to receiving a doctoral degree often are hired as assistant professors on a provisional basis, but it is unusual for them to be awarded tenure without a doctorate. The fact that David was is a testament to his intellectual firepower, Wright said. Harvard awarded David a doctorate in 1973 based on his prolific published research.

In 1978, he was appointed the William Robertson Coe Professor of American Economic History. From 1979 to 1983, David served as chair of the Department of Economics. During this time, he proposed the creation of the Center for Economic Policy Research. He chaired the planning group for the center.

“Paul was a giant in his field‚ one of the leading economic historians in the world,” said John Shoven, the Charles R. Schwab Professor of Economics, Emeritus, and a former director of the center. “He wasn’t a scholar with a narrow specialty. He had a very broad knowledge of economics.”

Technology diffusion

David covered a lot of territory in his research, including historical demography, macroeconomics, natural resources, slavery, migration, and climate change, but he was particularly interested in what determines whether a business sector will adopt an innovation. In various studies, he found that factors other than the fundamental superiority of a new technology—factors such as the structure of networks or the costs of information transmission—influenced its diffusion.

He came to such a conclusion in one of his most-cited papers, “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY,” which appeared in 1985 in The American Economic Review. David argued that the QWERTY keyboard layout became the standard not because it was optimal but because typewriter manufacturers and typists had strong incentives to settle on a single keyboard configuration around the turn of the 20th century.

In a 1990 paper, David examined why computer technology did not initially improve business productivity, comparing the situation to the lack of change in productivity that followed the introduction of an efficient electrical generator. Although the generator was ready for the market around 1880, it wasn’t until the 1920s that electricity showed a measurable effect on manufacturing output because American industry had to undergo a massive restructuring to take advantage of the new power source. David asserted that businesses adopting computer technology faced analogous restructuring challenges.

“Not only was he a great economic historian who laid the foundation for the understanding of compatibility and technology adoption, but he was also a polymath, having studied everything from demographics to the economics of science,” said Matthew O. Jackson, the Trione Chair of the Department of Economics and the William D. Eberle Professor in Economics. “He was knowledgeable and happy to talk about any topic you wished.”

‘A gifted adviser’

During his six decades at Stanford, David mentored many students who said they valued his teaching and feedback.

“Paul was an unusual economist, someone with wide-ranging interests and an openness to learning from other disciplines,” said Timothy Guinnane, professor emeritus of economics at Yale University, who earned his doctorate at Stanford in 1988 and was a David advisee for his dissertation. “His many accomplishments speak for themselves. He was also a gifted adviser. Paul had a deep and infectious curiosity that made everyone around him understand the great joy to be had in figuring things out.”

David authored or co-authored hundreds of articles and book chapters and co-edited several books. He served on the editorial boards of roughly 10 journals, including those of the Journal of Economic History, Explorations in Economic History, and Historical Methods. He also was editor of Economics of Innovation and New Technology.

Among his many honors, he was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Econometric Society, the American Philosophical Society, and the British Academy. He served terms as president of the Economic History Association and president of the Western Economic Association International. He was a Guggenheim Fellow from 1975 to 1976.

In 1994, David was elected a senior research fellow at All Souls College at the University of Oxford and for the next decade split his time between Oxford and Stanford. When he officially retired from Stanford in 2002, he was appointed the first senior fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute, where he remained active until 2008.

David is survived by his wife of 41 years, Sheila Johansson; son, Matthew David; daughter, Rachel David; stepson, Kenneth Johansson; stepdaughter, Elizabeth Allan; and five grandchildren.

In lieu of flowers, contributions in David’s memory can be made to the American Civil Liberties Union or Doctors Without Borders.