Research by Stanford sociologist reveals how and why privileged defendants fare better in criminal court than non-privileged ones.

Race and class make a difference in experiences and outcomes for criminal defendants in a system that emphasizes control and getting defendants to give in, according to sociologist Matthew Clair.

A chance encounter five years ago in a Chicago-area courtroom altered the course of sociologist Matthew Clair’s academic life. While a graduate student researching the criminal justice system, Clair and a colleague often observed courtroom proceedings in cities they were visiting.

While sitting in the gallery of a courtroom one day, Clair was startled to hear the prosecutor say, “Is Clair coming from lockup?” Clair wondered if his last name was more common than he had assumed. His father’s family hailed from Chicago, and Clair had had some contact with them over the years, but he was still shocked when a man who could have been his doppelgänger walked into the courtroom.

“I later found out he was a first cousin,” said Clair, assistant professor of sociology in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “Seeing him, and seeing the possibility of me in him, made me realize again the privilege I’ve had growing up middle class.”

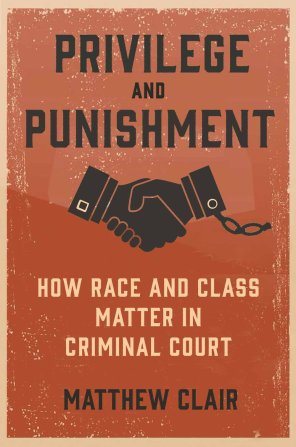

That encounter is one of many with criminal defendants that Clair references in his recently released book, Privilege and Punishment: How Race and Class Matter in Criminal Court (Princeton University Press, 2020). That unexpected brush with his cousin in the courtroom prompted Clair to pivot his research to examine the experience of defendants in the criminal justice system, specifically the attorney-client relationship, and the different ways that relationship manifests among privileged and disadvantaged defendants.

Privilege and agency

Clair defines non-privileged or disadvantaged people as those who live in neighborhoods with high levels of punitive police surveillance, who have routine and often racist or class-biased experiences with the legal system, limited social ties with people in power and limited access to financial resources. These are typically working-class people of color and the poor. By contrast, privileged people are those who have access to empowered social ties and financial resources and who rarely have negative encounters with police or other legal officials.

While much has been written about mass incarceration in the U.S., few scholars have explored the qualitative differences in the experiences of defendants, based on race and class, in the criminal justice system. What Clair found is that the power asymmetry in the attorney-client relationship plays out in a surprising and seemingly contradictory way for privileged versus disadvantaged defendants.

In mainstream institutions, like schools and doctor’s offices, if people have agency, learn the rules, and assert their rights, they are often rewarded with positive outcomes, prior research has shown. For instance, assertive students are more likely to get an exemption on a homework assignment and assertive patients often have more access to medical care. “Within the cultural sociology literature is the assumption that if only working class and poor people could learn those rules, they’d be treated better,” Clair said.

What Clair discovered is that in the criminal courts it’s exactly the opposite. “When non-privileged people learn the formal rules and their legal rights in the court system, they are punished,” he said. “These institutions have different unwritten norms and logics. Courts are about control and getting people to give in.”

Clair found that in a court setting, compliance often comes more easily to privileged rather than poor defendants. His research shows that privileged defendants, who are better able to hire an attorney, are also generally more trusting of their hired attorney and, therefore, more likely to cooperate and follow the attorney’s advice. Privileged defendants also tend to have had fewer negative experiences with the justice system, so they are less likely to feel the system is stacked against them. Clair also found that for privileged defendants, prior experiences with police are more often positive, including having social relationships with police or having been given a second chance by a police officer.

In contrast, disadvantaged defendants often had prior negative experiences with the police–including prior arrests, surveillance, and racism—and with the criminal justice system. According to Clair, these defendants often view their court-appointed defense attorneys with skepticism, seeing them as overworked, with heavy caseloads, and less inclined to fight hard for them. This often leads poor and working-class defendants of color to withdraw from cooperating with the attorney and instead try to advocate for themselves. They might ask for a new attorney or speak directly to the judge about their circumstances.

“For the disadvantaged, a relationship with a lawyer often results in coercion, silencing, and punishment. For the privileged, a relationship with a lawyer often results in leniency, ease of navigation, and even some rewards,” Clair writes in the book. “Therefore, race and class disparities in legal outcomes likely emerge, in part, from the taken-for-granted and hidden rules of the courts, which discriminate between defendants based on how they interact with their lawyers and present themselves in front of judges.”

Defendants seek respect

Clair draws on courtroom observations and interviews with 63 criminal defendants, representing a range of race and class backgrounds, as well as interviews with court officials, including lawyers and judges, in the Boston area.

“Defense attorneys are focused on mitigating outcomes, and privileged defendants agree with that goal,” Clair said. “One reason is that these defendants generally have respect in their lives, but disadvantaged defendants go back to a neighborhood that’s highly policed and where the police have been allowed to abuse them with impunity.”

For these defendants, achieving respect in terms of how they are treated while in the criminal justice system can be as important as the outcome of the case. So having their grievances against police misconduct heard or having their lawyer file motions on their behalf is an important part of whether they feel like justice has been achieved.

One experience shared by all the defendants that Clair surveyed was a profound sense of alienation during adolescence. “For disadvantaged people, their alienation put them into contact with the criminal justice system earlier on and the ability to have family or a broader social structure that was able to help them from going off the deep end was less available,” he said.

Clair concludes with recommendations for change within and outside of the existing system. These include allowing defendants to pick their own attorneys, encouraging judges to speak up more often to slow the process down and help defendants to feel heard, and teaching attorneys how to build better trust with clients.

He also advocates investing in social welfare programs to support disadvantaged communities and making better use of restorative justice programs, which emphasize the impact and consequences of a crime as well as finding ways for the responsible party to make reparations for the injury that was caused. As Clair concludes, “These alternatives to the existing criminal courts may be imperfect, but they encourage us to imagine how we might deal with social harms in the absence of police, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, and prison guards.”