Rigorous research practices improve scientific replication

Science has suffered a crisis of replication—too few scientific studies can be repeated by peers. A new study from Stanford and three leading research universities shows that using rigorous research practices can boost the replication rate of studies.

The research article described in this story has been retracted.

Science has a replication problem. In recent years, it has come to light that the findings of many studies, particularly those in social psychology, cannot be reproduced by other scientists. When this happens, the data, methods, and interpretation of the study’s results are often called into question, creating a crisis of confidence.

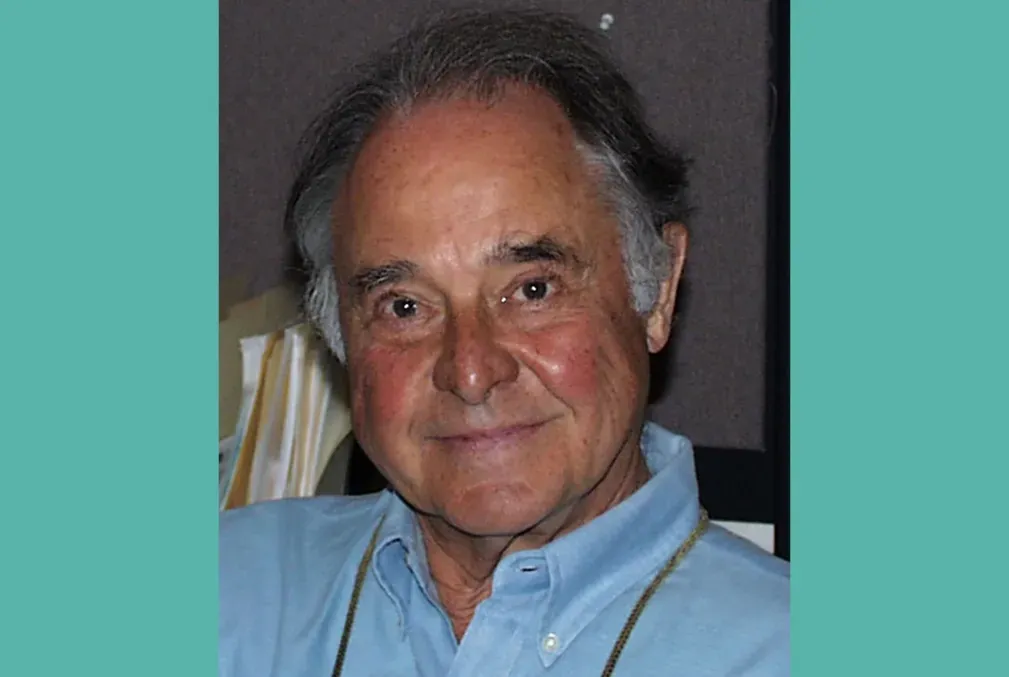

“When people don’t trust science, that’s bad for society,” said Jon Krosnick, the Frederic O. Glover Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences. Krosnick is one of four co-principal investigators on a study that explored ways scientists in fields ranging from physics to psychology can improve the replicability of their research. The study, published Nov. 9 in Nature Human Behavior, found that using rigorous methodology can yield near-perfect rates of replication.

“Replicating others’ scientific results is fundamental to the scientific process,” Krosnick argues. According to a paper published in 2015 in Science, fewer than half of findings of psychology studies could be replicated—and only 30 percent for studies in the field of social psychology. Such findings “damage the credibility of all scientists, not just those whose findings cannot be replicated,” Krosnick explained.

Publish or perish

“Scientists are people, too,” said Krosnick, who is a professor of communication and of political science in H&S and of social sciences in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “Researchers want to make their funders happy and to publish head-turning results. Sometimes, that inspires researchers to make up or misrepresent data.

Almost every day, I see a new story about a published study being retracted—in physics, neuroscience, medicine, you name it. Showing that scientific findings can be replicated is the only pathway to solving the credibility problem.”

Accordingly, Krosnick added that the publish-or-perish environment creates the temptation to fake the data or to analyze and reanalyze the data with various methods until a desired result finally pops out, which is not actually real—a practice known as p-hacking.

In an effort to assess the true potential of rigorous social science findings to be replicated, Krosnick’s lab at Stanford and labs at the University of California, Santa Barbara; the University of Virginia; and the University of California, Berkeley set out to discover new experimental effects using best practices and to assess how often they could be reproduced. The four teams attempted to replicate the results of 16 studies using rigor-enhancing practices.

“The results reassure me that painstakingly rigorous methods pay off,” said Bo MacInnis, a Stanford lecturer and study co-author whose research on political communication was conducted under the parameters of the replicability study. “Scientific researchers can effectively and reliably govern themselves in a way that deserves and preserves the public’s highest trust.”

Matthew DeBell, director of operations at the American National Election Studies program at the Stanford Institute for Research in the Social Sciences is also a co-author.

“The quality of scientific evidence depends on the quality of the research methods,” DeBell said. “Research findings do hold up when everything is done as well as possible, underscoring the importance of adhering to the highest standards in science.”

Transparent methods

In the end, the team found that when four “rigor-enhancing” practices were implemented, the replication rate was almost 90 percent. Although the recommended steps place additional burdens on the researchers, those practices are relatively straightforward and not particularly onerous.

These practices call for researchers to run confirmatory tests on their own studies to corroborate results prior to publication. Data should be collected from a sufficiently large sample of participants. Scientists should preregister all studies, committing to the hypotheses to be tested and the methods to be used to test them before data are collected, to guard against p-hacking. And researchers must fully document their procedures to ensure that peers can precisely repeat them.

The four labs conducted original research using these recommended rigor-enhancing practices. Then they submitted their work to the other labs for replication. Overall, of the 16 studies produced by the four labs during the five-year project, replication was successful in 86 percent of the attempts.

“The bottom line in this study is that when science is done well, it produces believable, replicable, and generalizable findings,” Krosnick said. “What I and the other authors of this study hope will be the takeaway is a wake-up call to other disciplines to doubt their own work, to develop and adopt their own best practices, and to change how we all publish by building in replication routinely. If we do these things, we can restore confidence in the scientific process and in scientific findings.”

Acknowledgements

Krosnick is also a professor, by courtesy, of psychology in H&S. Additional authors include lead author John Protzko of Central Connecticut State University; Leif Nelson, a principal investigator from the University of California, Berkeley; Brian Nosek, a principal investigator from the University of Virginia; Jordan Axt of McGill University; Matt Berent of Matt Berent Consulting; Nicholas Buttrick and Charles R. Ebersole of the University of Virginia; Sebastian Lundmark of the University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; Michael O’Donnell of Georgetown University; Hannah Perfecto of Washington University, St. Louis; James E. Pustejovsky of the University of Wisconsin, Madison; Scott Roeder of the University of South Carolina; Jan Walleczek of the Fetzer Franklin Fund; and senior author and project principal investigator author Jonathan Schooler of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

This research was funded by the Fetzer Franklin Fund of the John E. Fetzer Memorial Trust.

Competing Interests

Nosek is the executive director of the nonprofit Center for Open Science. Walleczek was the scientific director of the Fetzer Franklin Fund that sponsored this research, and Nosek was on the fund’s scientific advisory board. Walleczek made substantive contributions to the design and execution of this research but as a funder did not have controlling interest in the decision to publish or not. All other authors declared no conflicts of interest.