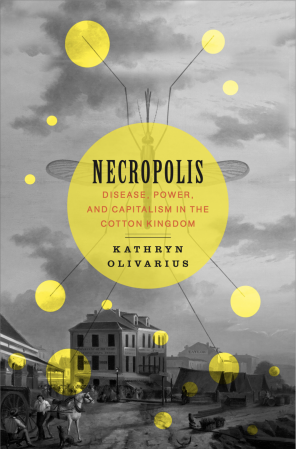

Professor Kathryn Olivarius on disease and discrimination in the antebellum South

In her new book Necropolis, Olivarius explores how immunity to yellow fever became a form of social and economic capital that exacerbated inequity in 19th-century New Orleans.

In the 1800s, antebellum New Orleans—the epicenter of America’s slave and cotton industries—was repeatedly visited by devastating epidemics of yellow fever. This seasonal mosquito-borne virus killed roughly half of the people it infected. But it also created the conditions for "immunocapitalism,” a system of class rule that favored people immune to yellow fever, argues Stanford historian Kathryn Olivarius. For people seeking economic, political, and social power in 19th-century New Orleans, it was crucial to survive yellow fever and gain immunity.

In her newly released first book, Necropolis: Disease, Power, and Capitalism in the Cotton Kingdom (Harvard University Press, 2022), Olivarius explains that in the sixty years leading up to the American Civil War, capitalists in New Orleans used anything at their disposal—such as laws and racial tensions—to subjugate other people and create wealth for themselves.

“Immunity was no different,” said Olivarius, assistant professor in the Department of History in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “In this system of class rule, people who claimed to be immune used their immunity and the vulnerability of others to consolidate their power.”

Necropolis explores why so many people died from yellow fever in antebellum New Orleans and how their deaths worsened inequity in a society that was already highly discriminatory.

A scholar of U.S. history, Olivarius has researched and written extensively on the American South in the 19th century. She said that while other historians have studied New Orleans during this period, their scholarship tends to focus more on themes of westward expansion, slavery, and the development of the cotton kingdom and less on the influence of disease.

“I came to think about yellow fever less as background noise and more as dark matter,” she said. “You can’t ignore this because health, disease, and immunity all deeply informed how people saw themselves, how they saw other people, and how they understood their place in society in New Orleans.”

Opportunity and acclimation

Between the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the onset of the Civil War in 1861, New Orleans was a major hub of economic activity dominated by slave trading and cotton exportation. During this time, thousands of people came to the city, including free people of color from across the South and Caribbean, opportunity-seeking white men from Northern states, Europeans escaping famine and political upheaval, and enslaved people brought to New Orleans in the domestic slave trade. But as yellow fever gripped the city, these outsiders arrived at their own risk.

Yellow fever is a horrific and painful disease. There is no known cure, but the symptoms can be treated to help the patient’s immune system fight the infection. Infected people may experience fever, headaches, muscle pain, and nausea. If their condition worsens, infected people often suffer from a yellowing of the eyes and skin, internal bleeding, and organ failure. This second, more toxic phase can lead to death. At the time, little was known about the disease, such as where it came from and how to treat it. What was known was that half of those afflicted died while the half who survived gained lifelong immunity.

In New Orleans, citizens were identified by their immunity status: those who got sick, recovered, and became immune were “acclimated,” and uninfected people or those who could not prove—or convince others of—their immunity were “unacclimated.”

“One of the first things that people learned when they arrived in Louisiana was just how important and invaluable immunity was if they wanted to get ahead there,” Olivarius said.

She writes that in 1806, a young German merchant named Vincent Nolte immigrated to New Orleans and three months later fell gravely ill with yellow fever. He got lucky and survived. Then, as an acclimated white man, he enjoyed certain privileges that catalyzed his success. Nolte could secure bank loans, move first on investment opportunities, command labor, travel safely, and socialize with the elite. Olivarius writes: “What had made him sick made him strong.” Nolte would leverage his immunity—as well as his race, gender, and connections—to his benefit and go on to transform the cotton market and become one of the most powerful merchants in New Orleans.

But other people—such as enslaved Black people—couldn’t take advantage of their immunity in the same way and instead saw the benefit of their acclimation transfer to others. For example, when John Palfrey, a white cotton planter and slave owner, went into deep debt and his creditors asked him to turn over some of the people he enslaved, he devised a calculation that convinced the creditors that acclimated enslaved people were more valuable.

“For men like Palfrey, Black people’s acclimation was a risk reducible to a numerical value, and it was his prerogative, as a white enslaver, to leverage it for his gain,” Olivarius writes. “In essence, he held financial ownership of their risk.”

Epidemic trends

Olivarius has been studying the links between disease and discrimination for more than a decade. In her book, she explains that throughout history, disease has often been described as a “social leveler” that “flattened social and economic asymmetries, increased the bargaining power of surviving workers, renewed people’s sense of common humanity, and reaffirmed their subservience to an omnipotent God.” But in 19th-century New Orleans, yellow fever did the opposite.

“It didn’t necessarily create new inequalities; it just exposed the ones that were already there and exacerbated them,” she said.

Olivarius said that social trends caused by yellow fever epidemics in 19th-century New Orleans have resurfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ability of wealthier citizens to shelter themselves from disease exposure and the spread of misinformation are two examples.

“When people are scared, they’re more prone to misinformation and to look for scapegoats or for people to blame. This is a truism throughout history,” Olivarius said, noting that disease is also often political. “Disease can be a way of fundamentally fracturing people and dividing us, so I was not shocked—though disappointed—to see that play out again with COVID-19.”

Sourcing information

The historical record abounds with accounts of the ways in which yellow fever influenced the everyday lives of people in antebellum New Orleans. Olivarius visited numerous archives at universities, museums, and historical societies across three continents to pore through old newspapers, municipal records, medical and hospital records, personal letters and diaries, and life insurance applications, which included medical questionnaires.

“Life insurance applications are my favorite sources to work with,” she said. “They provide a rare and unvarnished window into a person’s medical history. Southern applicants were deeply incentivized not to lie about their general health, or alcohol consumption, or most of all their immune status, or else their policy would be voided.”

Necropolis is also informed by years of Olivarius’s own scholarship. She has conducted extensive research on the American South, slavery, and slave revolts, including the Haitian Revolution. The book is also born out of her lifelong fascination with disease and the ways in which it influences people’s lives.

“Since I was a kid, I’ve always been obsessed with disease history, so perhaps it was written in the stars that I’d end up writing about it in some capacity,” Olivarius said. She added that although the topic is often gruesome, it ultimately resonates with most people, including her students.

“Disease is one of our most universal experiences, so people can easily relate to it,” she said.