Team co-led by Stanford researcher awarded $14M to conduct political survey

Shanto Iyengar is co-leading an effort to survey thousands of Americans before and after the 2024 presidential election, a period that will likely be marked by extreme volatility and uncertainty in U.S. politics.

A team of researchers led by political scientists at Stanford University and the University of Michigan was recently awarded $14 million from the National Science Foundation to collect data on voting, political participation, and public opinion during the 2024 presidential election cycle.

The team oversees the work of American National Election Studies. Since 1948, ANES, originally known as Michigan Election Studies, has conducted in-depth surveys of voting-age Americans before and after presidential elections. Data from every ANES survey are free and available to the public.

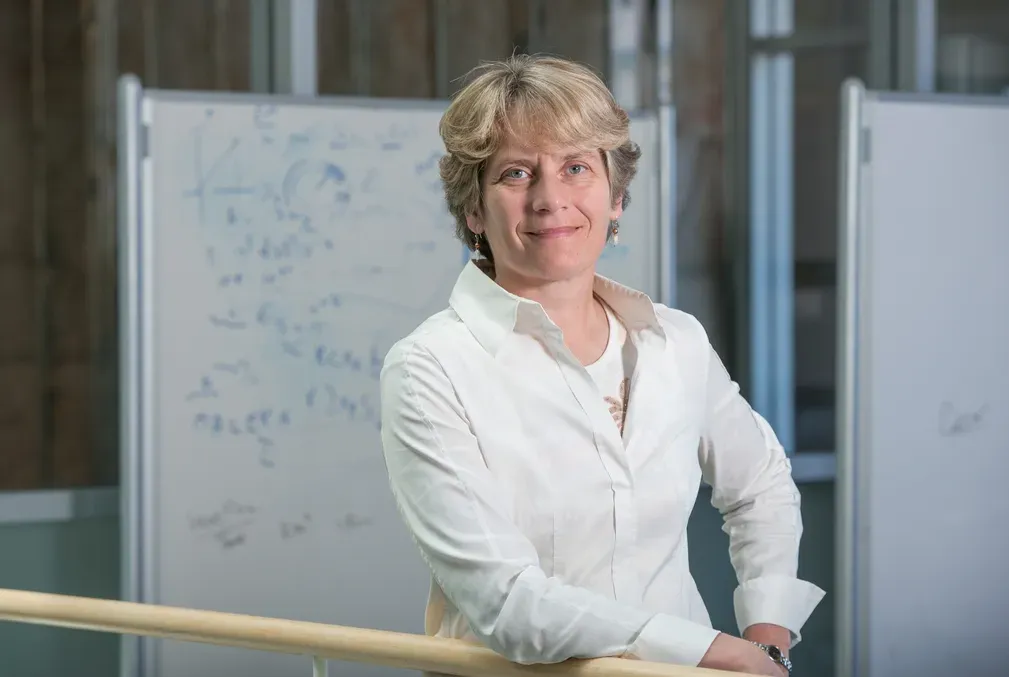

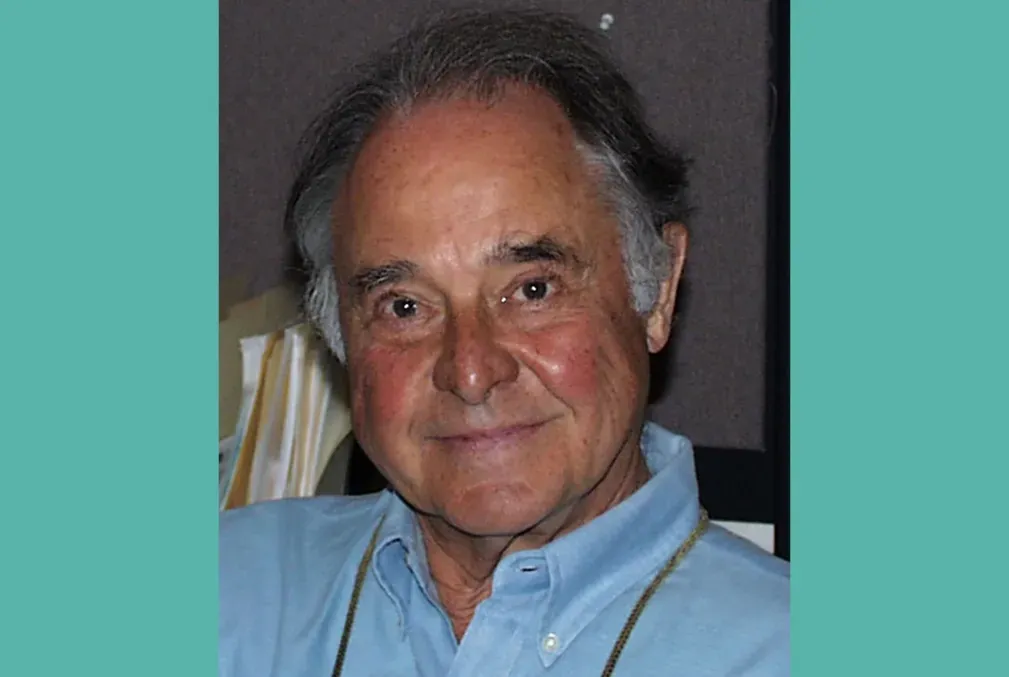

Shanto Iyengar, a professor of political science and of communication at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, and Nicholas A. Valentino, a professor of political science at the University of Michigan, are principal investigators of the project.

Here, Iyengar, who holds the William Robertson Coe Professorship, discusses the significance of the long-running data-collection effort and what the team hopes to accomplish in the run-up to and in the wake of the next presidential election.

Why are the ANES surveys important?

The results provide a picture of how political opinion and voter concerns have changed over time—at this point, we have more than seven decades’ worth of data—and this has proved indispensable for researchers. One study from 2018 found that ANES data was used in a third of more than 1,100 articles on political behavior published between 1980 and 2009.

What’s more, we are living in one of the most turbulent periods of recent American history. I’m quite sure that the data we collect in 2024 is going to be used by virtually every student of American politics. It’s been nearly two years since Donald Trump was in office, but he still holds enormous sway over a large portion of the electorate. The new surveys will help reveal what the Trump phenomenon has meant in the long term. Did it actually alter people’s attitudes, and did they stay changed over time? Or was it just a one-shot deal?

Who will you survey in 2024?

We plan to survey around 7,000 Americans. Participants will be from every state except Hawaii and Alaska. The surveys used to all be conducted face to face, but that has changed in recent decades because it’s prohibitively expensive to send interviewers to all participants’ homes. Most of the surveys in 2024 will be conducted via videoconference, telephone, or online questionnaires. Still, about 300 interviewers will fan out across the nation to conduct in-person interviews.

Do the interviews produce more accurate data than the questionnaires?

That’s not completely clear. Interviewees may feel more constrained about expressing their true beliefs because they want to appear respectful. People are much less hostile when they are interviewed, especially face to face. But when they’re responding to the questionnaires, they may not feel as many compunctions.

In any case, we’ve found that fewer people are willing to participate these days in long surveys on controversial topics. Even with financial inducements—all participants are paid to take the surveys—people have been turning us down. Politics is not something people enjoy discussing, especially today, when there’s so much polarization and so much division. I also think we’re increasingly becoming a society that is cynical about the intent of people who want to ask you questions.

What kinds of questions will participants be asked?

They’ll be asked hundreds of questions on a broad range of topics, including candidate preferences, congressional job performance, the state of the economy, and whether the country is on the right track. These are the kinds of topics that have been addressed since the surveys’ inception. About a third of the questions have essentially remained the same since the beginning, and the rest are new or were introduced at some point over the last 70 years. For example, surveys have asked about abortion since 1972, around the time Roe v. Wade was before the Supreme Court. This time we’ll be including a set of questions concerning the Dobbs case reversing Roe v. Wade. There will also be many other questions more specifically tied to the times we’re in, but they haven’t been formulated yet. But in 2020, for example, surveys asked questions related to COVID-19 policy, self-censorship, immigration, misinformation, and urban unrest and rioting.

What are some new elements of ANES surveys?

In 2016, we started collecting longitudinal data from about 3,000 participants. They took the surveys that year and again in 2020, and they’ll also take the 2024 surveys. Their responses could be especially valuable since it will reflect how views of Americans have evolved over an eight-year span.

Another new facet of ANES is tracking the data of participants’ Facebook accounts, which we did before and after the 2020 presidential election and will do again during the 2024 presidential election cycle. More than 5,000 participants consented to have their Facebook data collected in 2020, so we have actual behavioral data showing what political content they encountered on Facebook and what they did on that platform. We can link this data to participants’ survey responses.

We’ve also been collaborating with General Social Survey, which collects data on the social characteristics of American adults, since 2020. A subset of GSS participants also takes the ANES surveys, enabling researchers to link a wealth of social and demographic information to political attitudes and behavior. This is a major innovation for ANES. The collaboration will enable, for example, in-depth analyses about the impact of economic mobility on political predispositions.

Beginning in 2024, we will introduce an interactive data platform that will enable people to track trends in the data over time. This will be a huge resource for journalists and other observers of American politics.

ANES makes so many contributions to social science. It’s a public good that has an incredible impact.