Stanford introduces medical humanities minor

Combining the field of medicine with art, literature, film, history, policy, and the social sciences, a team of Stanford professors has shaped a new undergraduate minor that explores the rich terrain of the human experience.

Western medicine focuses on treating diseases using science and a scientific approach as a means to save lives. More recently, however, with our deepening understanding of the intersections of mental and physical health, it is becoming increasingly clear that science alone is not enough to satisfy the human need for well-being of both body and mind.

To meet this need, the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences has established a new medical humanities minor available to all undergraduates interested in exploring medicine and health through the lenses of the humanities and social sciences. Students can now declare their intent to pursue this minor.

In the new minor, students will learn to appreciate the human body and medical issues from multiple disciplinary and aesthetic perspectives. For example, students will learn to investigate and understand epidemics not only by using epidemiological data, but also by examining how epidemics are depicted and reflected in areas such as literature, painting, history, culture, and policy.

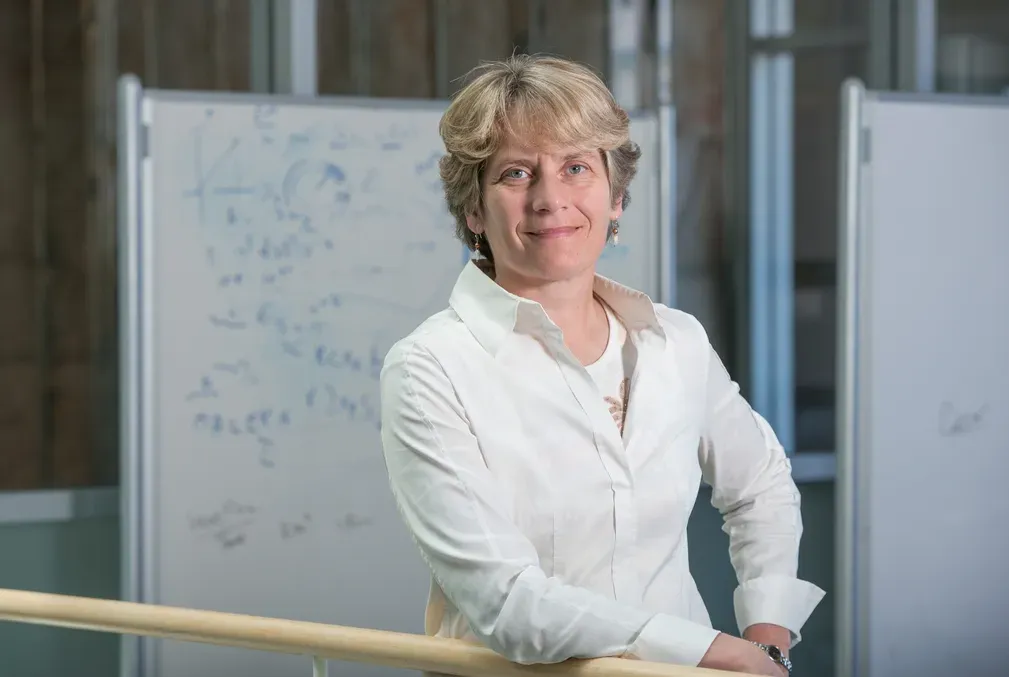

“We wanted to create a more holistic and unified view of human health and the human experience,” said Audrey Shafer, professor emeritum of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine at the Stanford School of Medicine, who jointly developed the new medical humanities minor with Tanya Luhrmann, the Albert Ray Lang Professor of Anthropology, and Laura Wittman, associate professor of French and Italian.

“As medicine becomes more complex, as people live longer, as technology grows ever more sophisticated, particularly toward the end of life, there is a need for a greater understanding of what it means to be healthy or to be ill and how human perspectives on health have changed over time,” Luhrmann added.

For Wittman, the minor is about putting ideas into action. “We see a real hunger on campus among undergraduates to learn and speak up in ways that address sociopolitical concerns about illness, trauma, gender and sexuality, disability, environmental degradation, and racial justice, among other relevant topics of our time,” she said. “Speaking up is the humanities.”

Broad inquiry

While premed, bioengineering, and other medically inclined students can use the minor to broaden their interpersonal knowledge and skills, the co-creators see a much wider appeal. The new minor is also relevant for undergraduates interested in exploring evolving notions of depression; how people working in the field of medicine are shaped by the emotional intensity of their work; and views of mortality, pain, and illness across cultures around the world, the co-creators explained.

“Potential candidates include virtually any undergraduate—computer scientists developing a more inclusive artificial intelligence; pre-law and political science students studying the ethical and political nuances of medicine; engineers designing more human-centered technologies; and creative writers, filmmakers, musicians, and artists giving greater voice to the human medical experience,” Luhrmann noted.

The new medical humanities minor spans three primary academic domains. The first is healing and the arts, which explores how art and literature enhance our capacity to listen and to understand human health. Second, there is a social domain explored through anthropology, history, and sociology. And third, there is a justice and policy component that explores the philosophical, ethical, and political facets of human health.

The minor requires one core course, The Medical Humanities, that will be taught by a rotation of faculty from varying disciplines as an introduction to the three key areas of the minor. Students must complete 25 units to earn the minor—four in the core course, one for participation in any of the medical humanities workshops hosted at the Stanford Humanities Center, and 20 additional units in at least four courses in two or more disciplines connected to medical humanities. A final presentation is also required.

Students in this minor will be in a unique position to both shape and drive this emerging field forward by leveraging the expertise, resources, and research in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Science and School of Medicine as well as the university’s exceptional art museums and performing arts venues.

Feeding the hunger

Wittman says there is an overt cultural component to medical humanities that compares how different societies have viewed health and medicine through time. Her current work in progress explores how narratives about what happens after death and classical myths of the underworld serve as a window into our own evolving attitudes on mortality in modern culture.

One of her courses that will be available to students in the new minor is Art and COVID: A Health Humanities Perspective. This course explores how artists around the world contributed to healing during the pandemic through poetry, painting, performance, and other forms of expression.

A key insight provided by the medical humanities minor is that a person’s disciplinary approach shapes their conclusions to a significant degree, Luhrmann, Shafer, and Wittman explained in their proposal for this minor. Using multiple approaches in a field of study can help reveal the complexity of the real world.

“Students will learn critical thinking, research, and presentation skills to promote self-reflection and self-understanding about health—of both body and mind. In the process, they will learn to collaborate to find solutions to major issues in our increasingly complex world,” Wittman said.

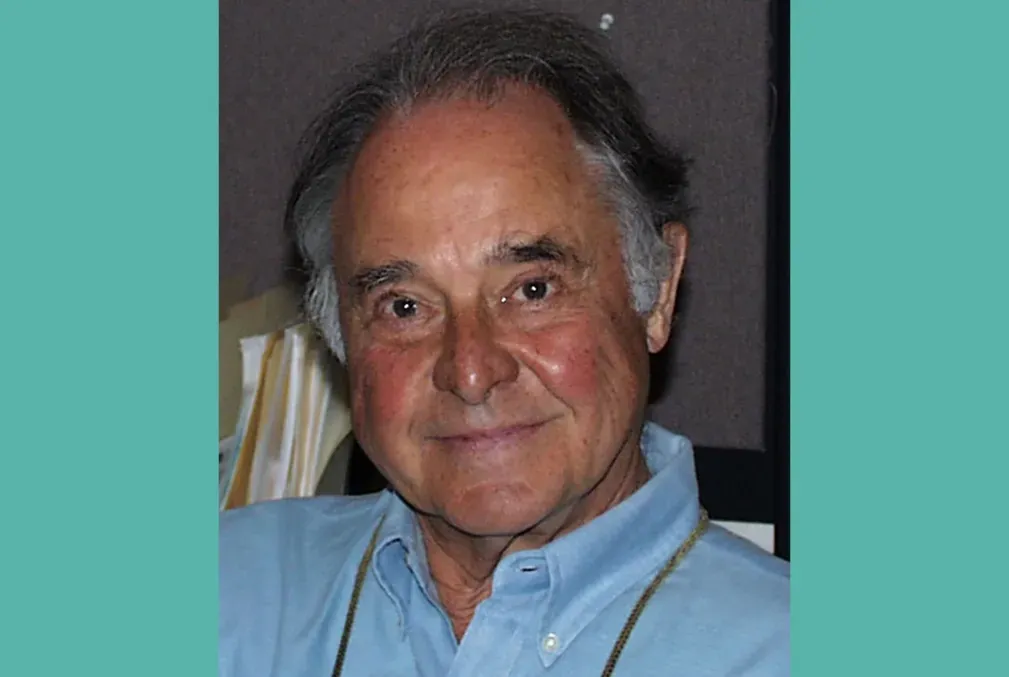

Previously, Luhrmann combined her dual interests in the sciences and arts in a course called Culture and Madness: Anthropological and Psychiatric Approaches to Mental Illness, co-taught with Daniel Mason, a psychiatrist and novelist. This course, which will be offered as part of the new minor, explores psychosis through what we know of psychiatric science, anthropological exploration, film, and storytelling.

“A film like Invasion of the Body Snatchers can teach the viewer quite a bit about psychosis,” Luhrmann said. “We found that as we mixed these humanistic approaches in new and interesting ways, the class size exploded from 30 to 170 students.”

“I was cleaning out my office the other day, and I found printouts of emails from the ’90s contemplating an undergraduate minor in medical humanities,” said Shafer, who recently retired. “I’m just bursting with happiness that it’s a reality.”

Students interested in learning more about the minor can contact Roya Aghavali: royavali [at] stanford [dot] edu (royavali[at]stanford[dot]edu)