Enzyme discovery helps unravel decades-old ribosome mystery

After making a protein, ribosomes can be reused or decommissioned—an outcome that impacts protein quality and possible protein-related diseases down the line. New research solves the 50-year-old mystery regarding the fate of spent ribosomes and suggests a dynamic enzyme is vital for the “quality control” process.

Stanford researchers have solved a half-century-old mystery regarding the intricate protein-making machines inside cells known as ribosomes. Ribosomes attach and deliver proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum, a lacy network that shuttles proteins around within cells and secretes them out of cells for use throughout the body. How ribosomes detach from the endoplasmic reticulum—a critical process for freeing them up for reuse—had never been worked out.

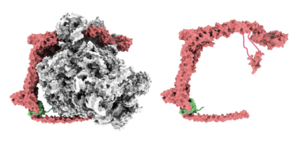

In a study recently published in the journal Nature, the Stanford researchers have at last pieced together the detachment puzzle. They showed that the binding of a large enzyme—a special kind of protein that speeds up, or catalyzes, chemical reactions without being altered by them—dubbed UFM1 E3 ligase, ultimately separates the ribosome from the endoplasmic reticulum. The enzyme, which is shaped like the letter C, wraps around the ribosome, possibly contributing to a sort of “quality control” performed within a cell to ensure its fleet of ribosomes remains fit for service.

By revealing a fundamental yet overlooked mechanism in cell biology, the results could improve our understanding of the everyday workings of our trillions of cells, as well as offer insights into certain neurodegenerative disorders and rare neurologic and skeletal human diseases with possible links to mutations in the UMF1 system.

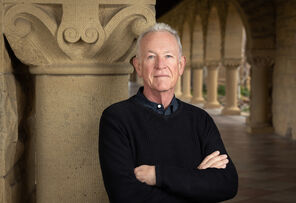

“Our findings answer a 50-year-old question in cell biology of how ‘spent’ ribosomes are released from the endoplasmic reticulum,” said Ron Kopito, a professor of biology at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences and the study’s senior author. “The work in our lab is now addressing this mechanism that biologists had left alone for decades and that textbooks don’t explain.”

“What we’re seeing suggests that the regulation of ribosome detachment allows for surveillance prior to releasing a ribosome back into the pool of free ribosomes that can be used again,” Kopito said.

A biomolecular “Swiss Army knife”

Paul DaRosa, a former postdoctoral researcher in Kopito’s lab who is now a protein biochemist at Cyrus Biotechnology in Seattle, Washington, co-led the study with Ivan Penchav, a graduate scholar at Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich. DaRosa and his Stanford colleagues performed a series of experiments that added trackable labels to a tiny protein called UFM1 (ubiquitin-fold modifier 1), part of a family of protein-modifying biomolecules. Previous research revealed that UFM1 is attached to a ribosomal protein, located at the point where ribosomes connect to the endoplasmic reticulum.

Tracking UFM1 allowed the researchers to trace the protein’s steps and see what other biomolecules it met along the way. The strategy singled out an enzyme, called UFM1 E3 ligase, catalyzes a reaction that attaches UFM1 to one of two major ribosome subunits.

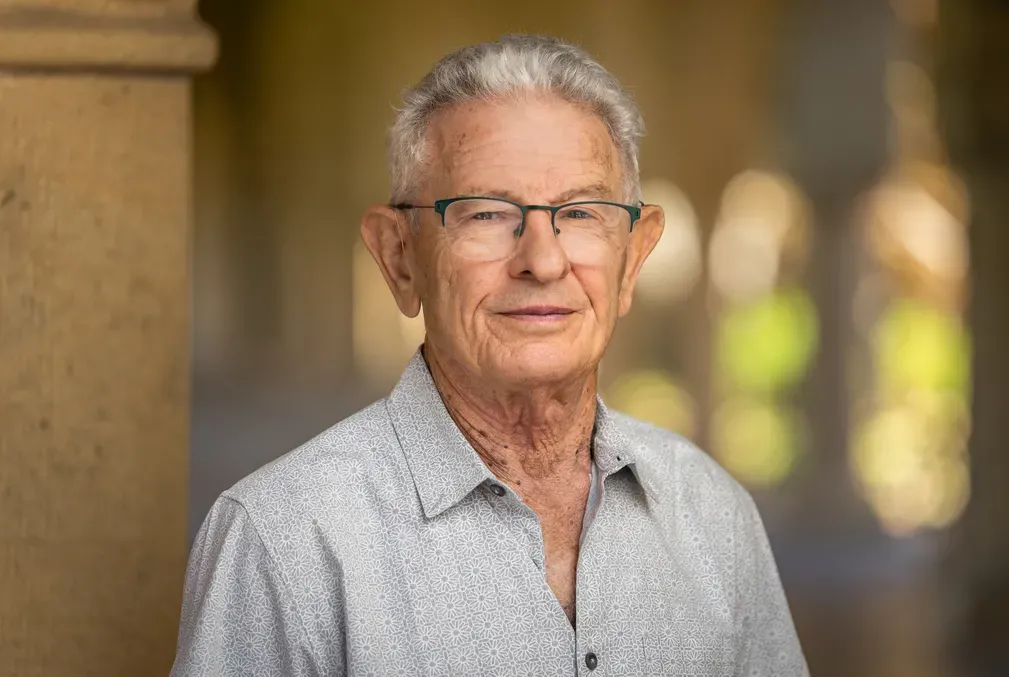

Co-author Roland Beckmann, a professor at Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, whose lab specializes in ribosome structural biology, helped uncover more clues in the 50-year ribosome release mystery. Beckmann was a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of biologist Günter Blobel, who won the Nobel Prize in physiology in 1999 for showing how ribosomes deliver newly made proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Blobel was unsuccessful in solving the endoplasmic reticulum release problem, partly on account of technology not being available at the time to provide key insights.

Decades later, Beckmann and colleagues had new technology at their disposal to help them determine the structure of the UFM1 E3 ligase's protein when bound to the ribosome and UFM1. This technology enabled them to create a model of how the enzyme elaborately probes various components of the ribosome, thanks to its long, curving C shape and substantial size.

The demonstrated dynamism of the enzyme prompted the researchers to compare UFM1 E3 ligase to a Swiss Army knife. “You can imagine UFM1 E3 ligase as a Swiss Army knife or a multitool that is partway open and has various tools sticking out,” DaRosa said. “The enzyme gloms onto the spent ribosome and is able to interact with all these different regions.”

For instance, one arm of the enzyme wraps around to the top of the spent ribosome where it seems to block any new transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules from binding. Those tRNAs are necessary for churning out new proteins. As a result of this blockage, one end of the enzyme prevents the spent ribosome from accidentally churning out proteins while it is still docked to the endoplasmic reticulum.

Fitting the multitool analogy further, a different, helical portion at the opposite end of the enzyme is what dislodges the ribosome subunit—and in effect the whole ribosome—from its binding location on the lacy network.

Still other “tools” stick out from the enzyme, and their functions are yet unknown. According to the Stanford researchers, other studies suggest that one of the enzyme’s uncharacterized subunits might recruit biomolecules involved in autophagy, the process whereby cells break down old, degraded proteins as well as damaged ribosomes—thus adding evidence to the enzyme’s putative role in ribosomal quality control.

“The enzyme has these other kinds of tools, but we’re not really sure what they’re doing yet,” DaRosa said. “We think they’re going to turn out to be important, and they will be the focus of additional studies.”

Keeping ribosomes “roadworthy”

Overall, the researchers think UFM1 E3 ligase is a key player in making sure used ribosomes “pass inspection” before returning to protein-making duty. Because proteins are the workhorses of biology—involved in everything from structure to motility to biochemical reactions—healthy cells must maintain an abundant set of operating ribosomes. And because ribosomes are so complex and thus metabolically costly to produce, they must continuously be recycled and repaired by cells.

As an analogy, Kopito offers a fleet of buses that a city must keep in service. “We think that the UFM1 E3 ligase detachment system builds in some regulation to the fate of the ribosome at that particular moment when the ribosome finishes making a protein at the endoplasmic reticulum,” he said. “Two things can happen—either the ribosome can be judged “roadworthy” and released right back into the pool of available buses, or the ribosome can undergo a degradation process, be taken off the road, and [be] expensively replaced with a new bus.”

Mutations in biomolecules involved in the broader regulation pathway, known as UFMylation, could explain some of the rare diseases associated with ribosome dysfunction or insufficiency, known as ribosomopathies, particularly Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, which is associated with pancreatic and bone marrow dysfunction, skeletal issues, and a high incidence of cancers including leukemia.

More generally, the UFMylation pathway appears to help cells deal with specific types of stresses associated with producing the abnormally shaped proteins that underlie so-called conformational diseases such as Alfa-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, though much work needs to be done to flesh out this possibility.

“By revealing the mechanisms behind how ribosomes leave the endoplasmic reticulum, we’ve made a biological discovery that will be a touchstone as we and others in our field continue to explore the UFMylation pathway,” Kopito said. “This is fundamental science, and we’ll see where it goes from here.”

Acknowledgements

Kopito is also a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Other Stanford co-authors include Samantha C. Gumbin, graduate student in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, School of Medicine; and Francesco Scavone and Magda Wąchalska, postdoctoral researchers in the Department of Biology, School of Humanities and Sciences. Additional co-authors include Joao A. Paulo and J. Wade Harper of Harvard University, Alban Ordureau of the Sloan Kettering Institute; Joshua J. Peter and Yogesh Kulathu of the University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland and Thomas Becker of Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich.

This study was supported by funding from the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine and the National Institutes of Health.