Two Stanford physicists win grants for ‘tabletop’ experiments with big implications

Stanford’s Giorgio Gratta and Jason Hogan are among 11 researchers whose proposals were selected from hundreds to receive funding for fundamental physics experiments. Each project will receive up to five years of funding from four foundations that pledged a combined $30 million to support the projects.

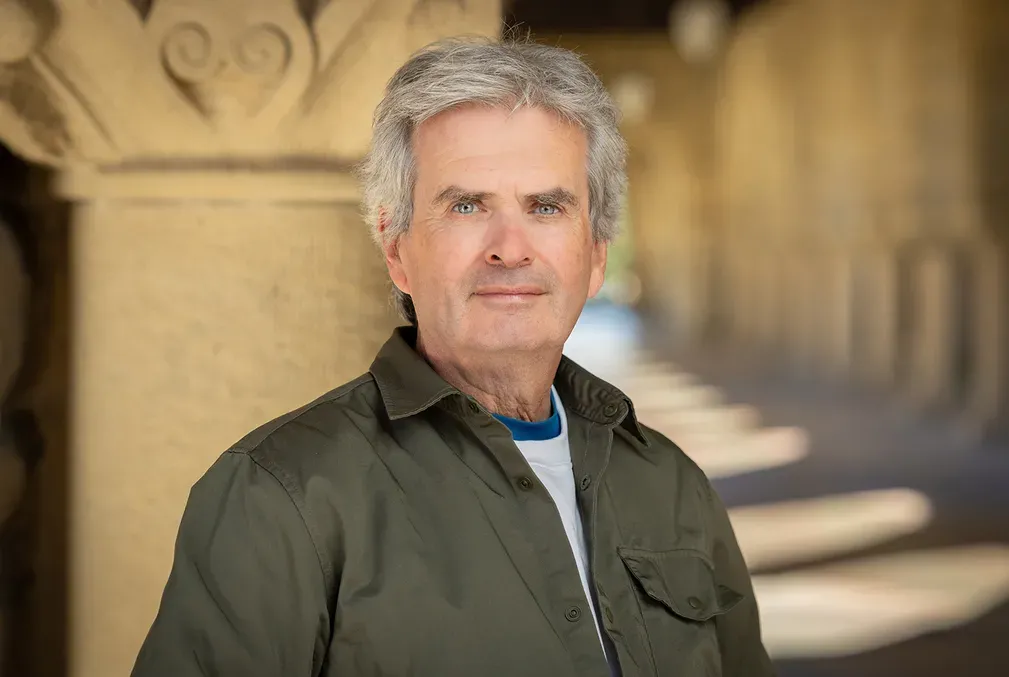

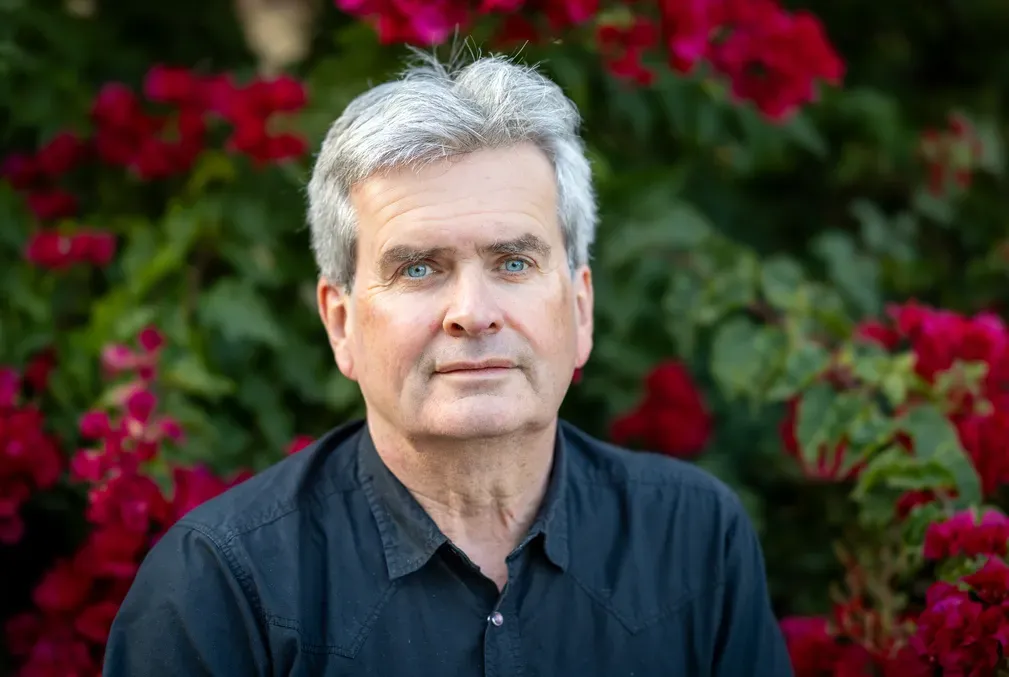

Two physicists in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, Giorgio Gratta and Jason Hogan, are among a select group of 11 researchers worldwide who will conduct fundamental “tabletop” physics experiments with funding from a consortium of math and science foundations that includes the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Simons Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the John Templeton Foundation.

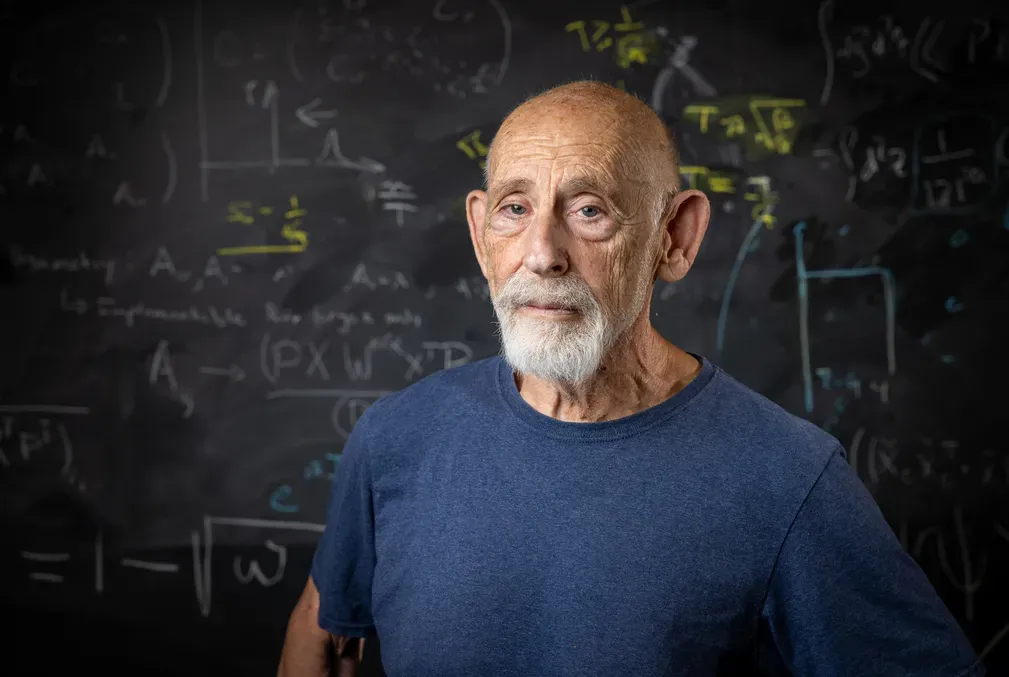

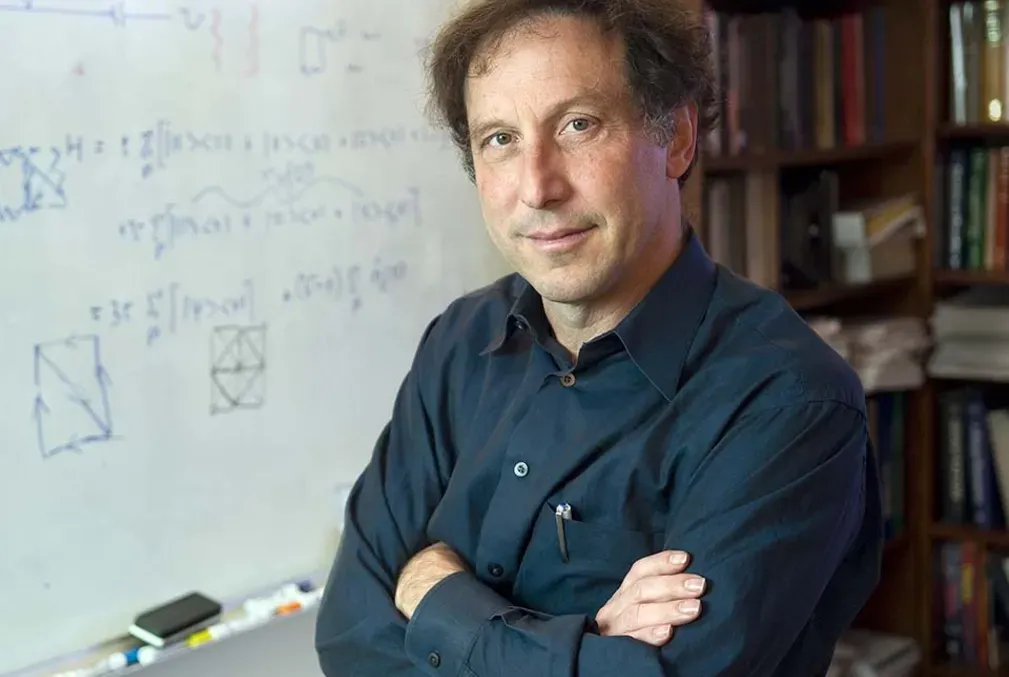

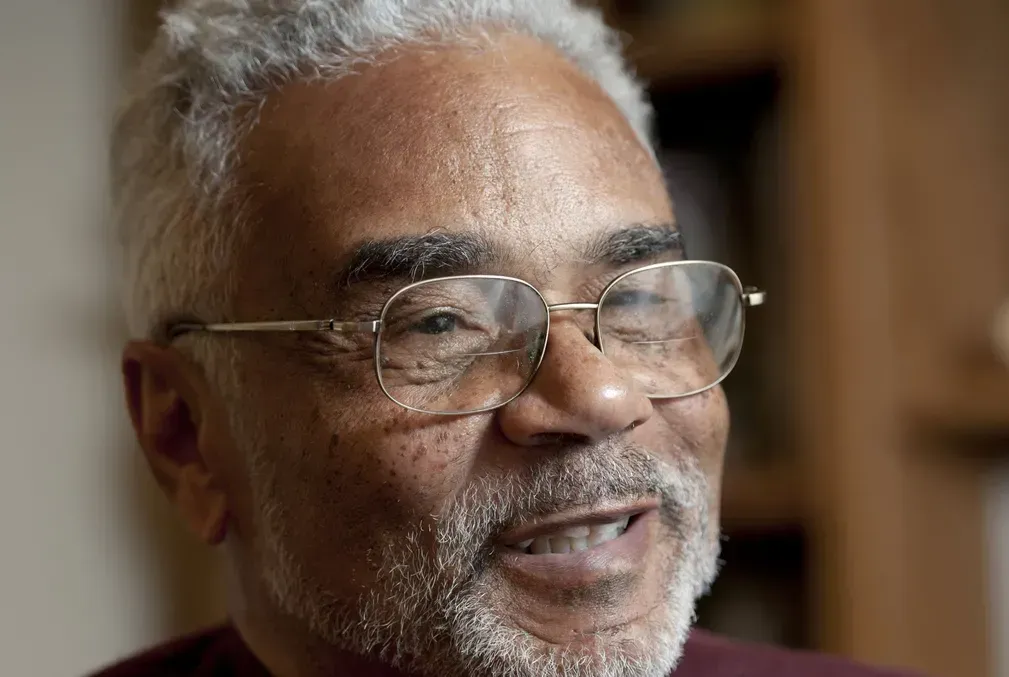

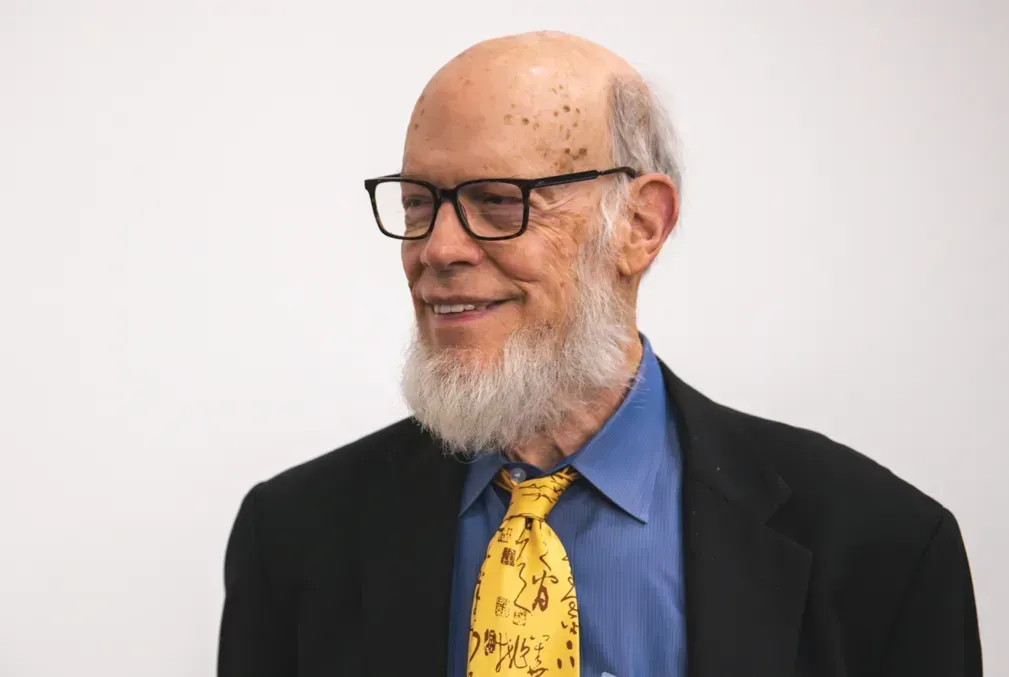

“We are grateful to these foundations for funding projects in basic science such as ours,” said Gratta, the Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor. “Their support will advance human knowledge in a critical area of physics.”

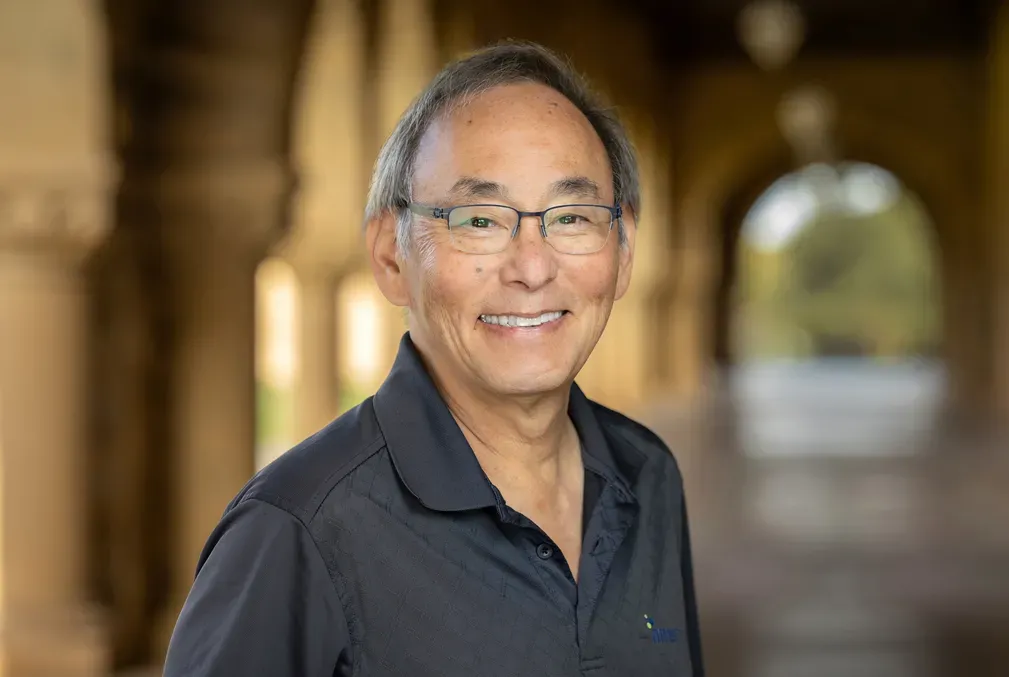

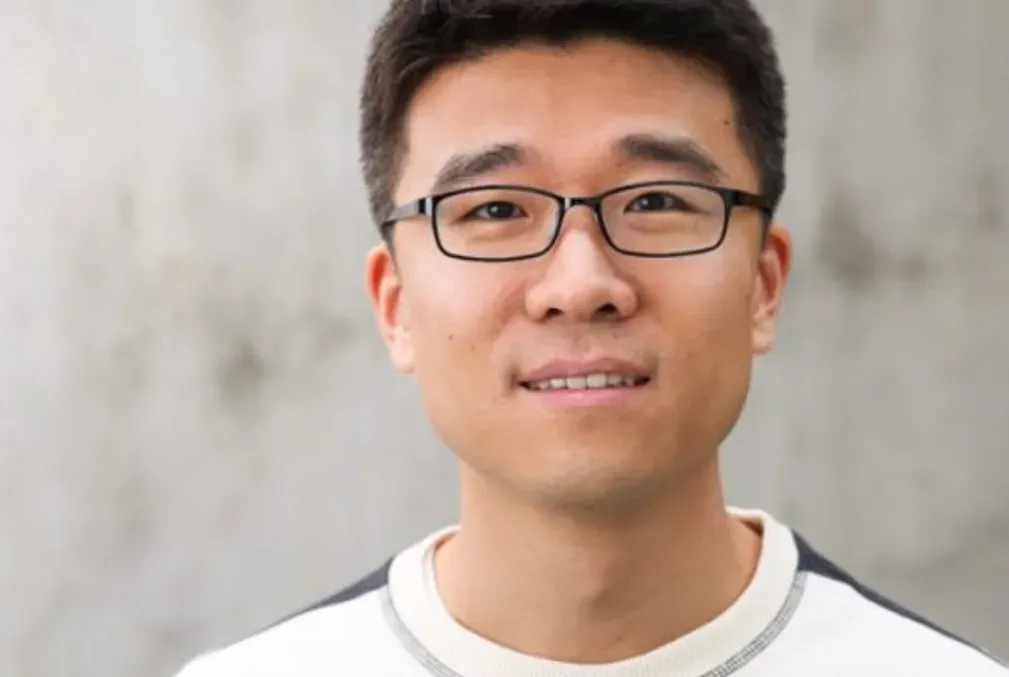

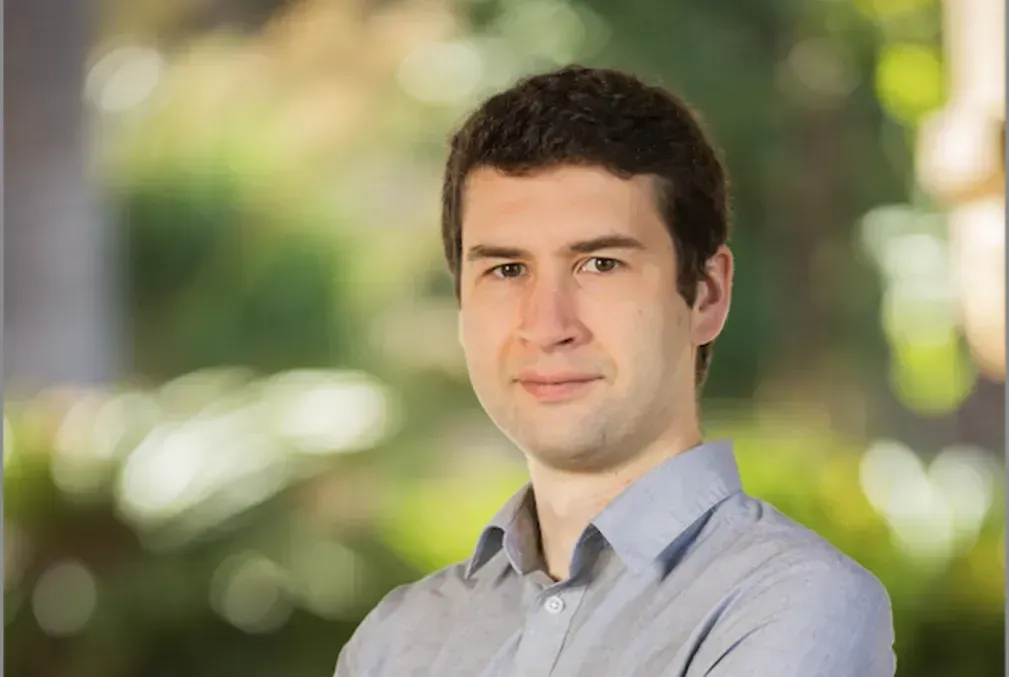

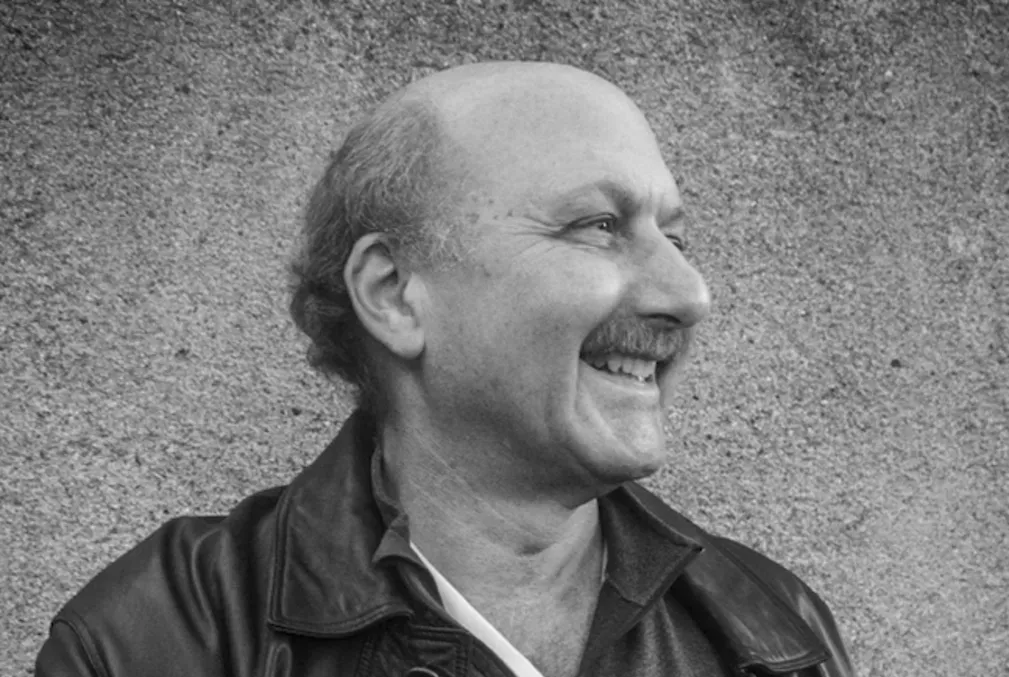

“This type of funding is crucial to the ongoing pursuit of answers to fundamental questions about how atoms are structured and how they function,” Hogan said. “My lab looks forward to contributing to that effort, and we are grateful to the foundations for their support of our work.”

The foundations have joined forces to amplify the impact of their funding across numerous smaller-scale experiments that can be conducted at the so-called “tabletop” level—within a standard single-room university research lab—yet whose outcomes could nonetheless alter our understanding of the physical world.

The 11 ambitious projects were chosen from hundreds of proposals submitted from around the world. A combined grant of $30 million will be disbursed to the named researchers over a five-year period. The diverse grant topics include searching for dark matter, building ultra-precise atomic clocks, and examining the intersection of general relativity and quantum mechanics. Stanford was the only university to receive two grants.

Gratta and Hogan will work independently. Gratta, who is the chair of Stanford’s Department of Physics, and his team will use nuclear spectroscopy to measure gravity at the tiniest of scales to test the long-held assumption that gravity works in the same way at submicron and macroscopic scales. Hogan will lead research that uses precision quantum sensing to measure the subtle difference between the electric charges of protons and electrons.

The payoff for both projects is pure science—knowledge that can be used to refine our understanding of the universe. Among fundamental interactions, “gravity is both the most obvious and yet the least understood,” Gratta explained. Until now, the force of gravity has been probed only at a scale of 50 microns or larger, a shortcoming concerning to physicists as much of theoretical physics has been driven by the assumption that the law of gravity holds true at all scales. Investigating gravity at ever-shorter distances is thus an essential frontier in experimental physics.

Similarly, Hogan’s work will use quantum sensing to measure possible differences between negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons with higher precision than ever before. To date, no variation in charge has been found, but the discovery of even an infinitesimal difference in charge between the two would indicate new physics at energy scales much higher than can be probed in existing particle colliders.