Early-career Stanford researchers honored for their cutting-edge studies in physics and social economics

The Infosys Prizes recognized the researchers’ work regarding exotic states of matter and the spread of prosocial gossip.

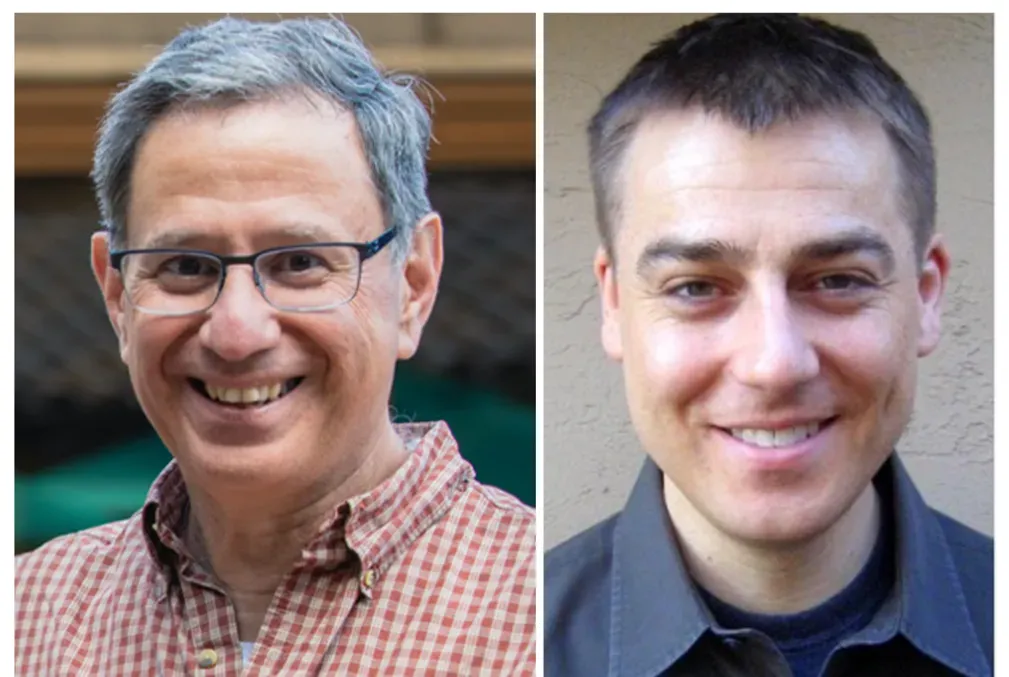

Two faculty members in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences recently received prestigious international prizes that recognize outstanding young researchers of Indian origin or those whose research impacts India.

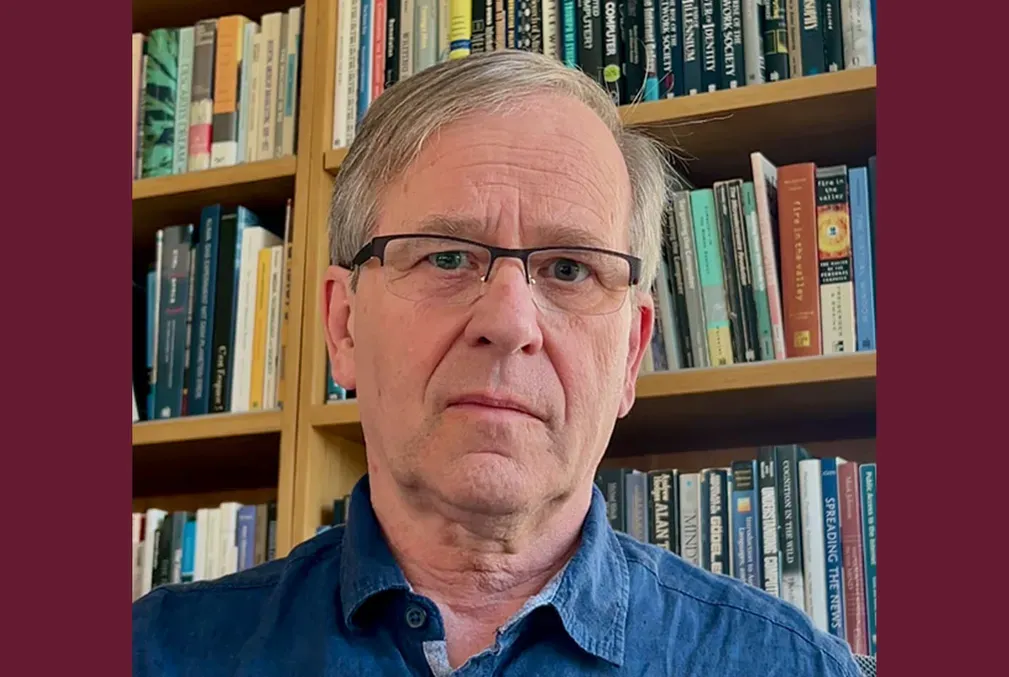

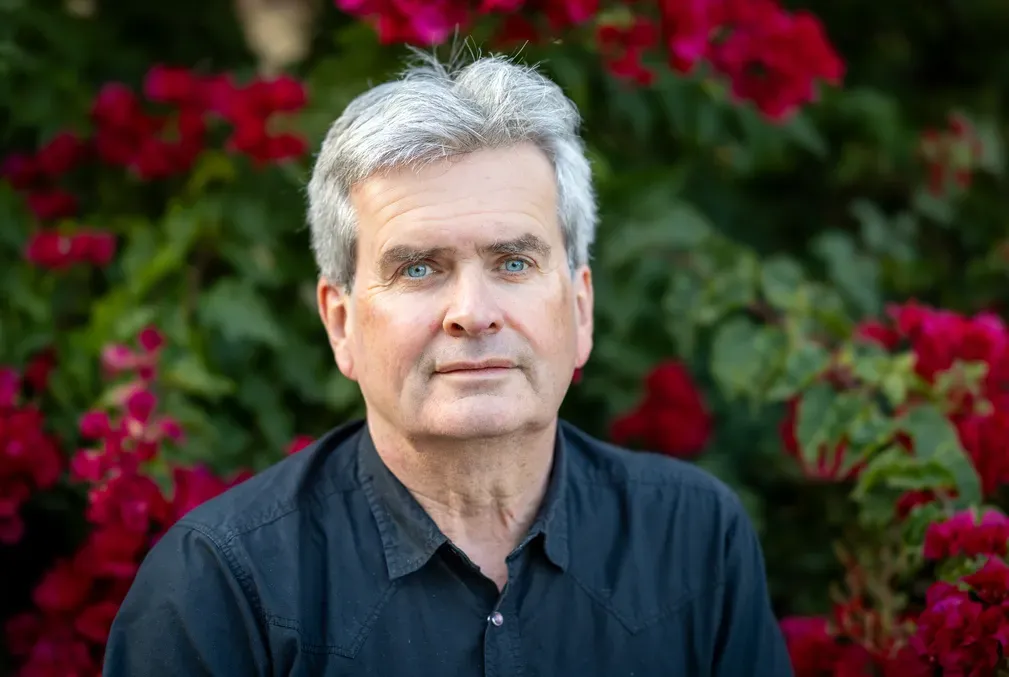

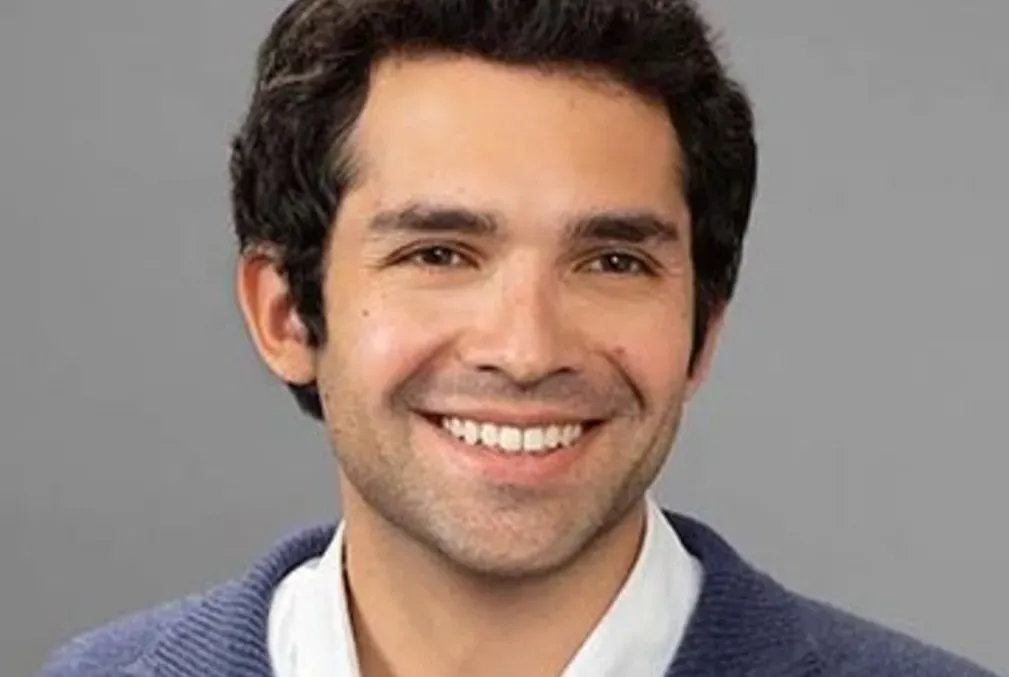

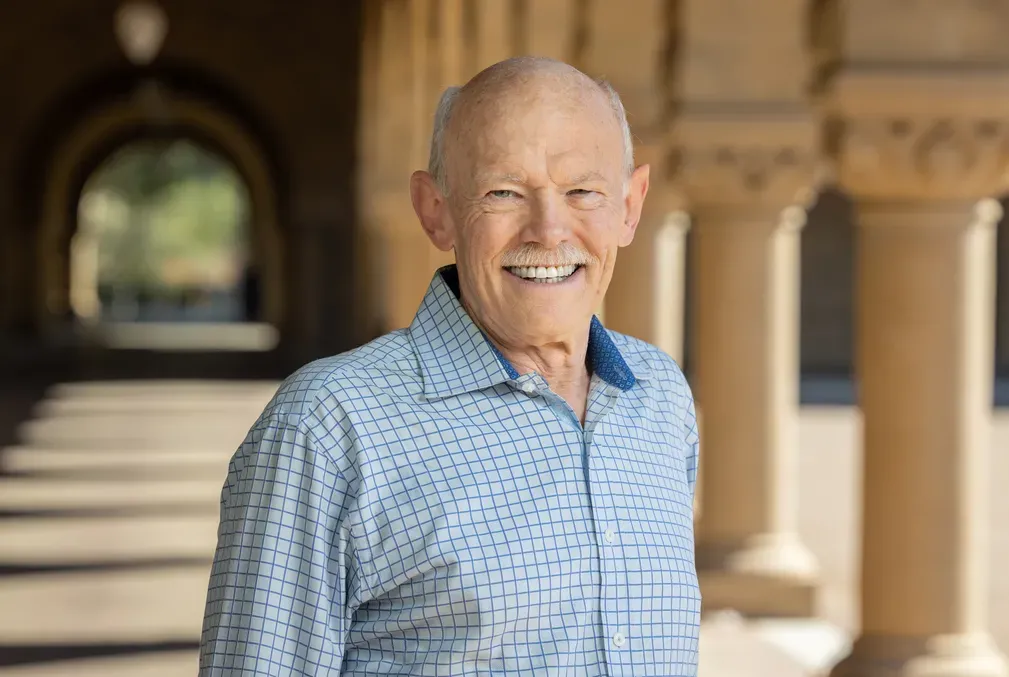

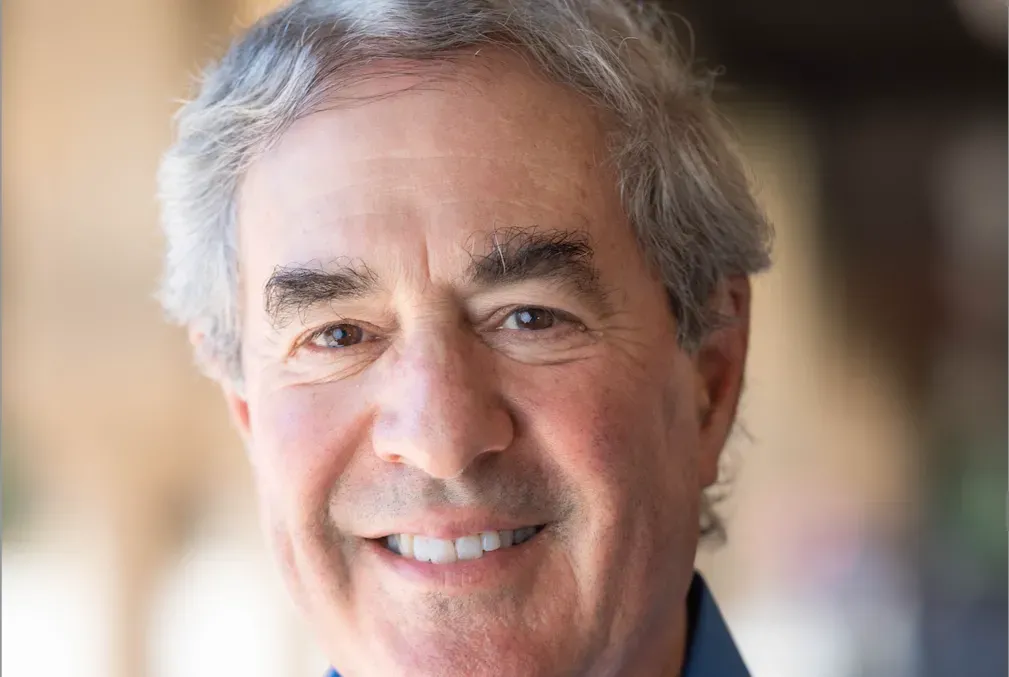

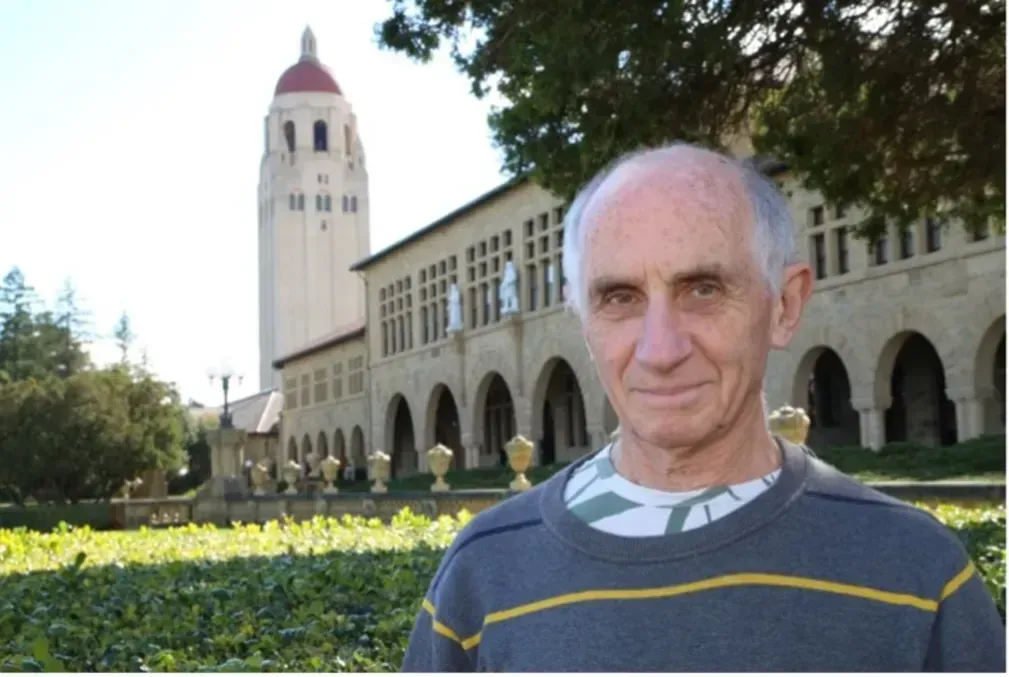

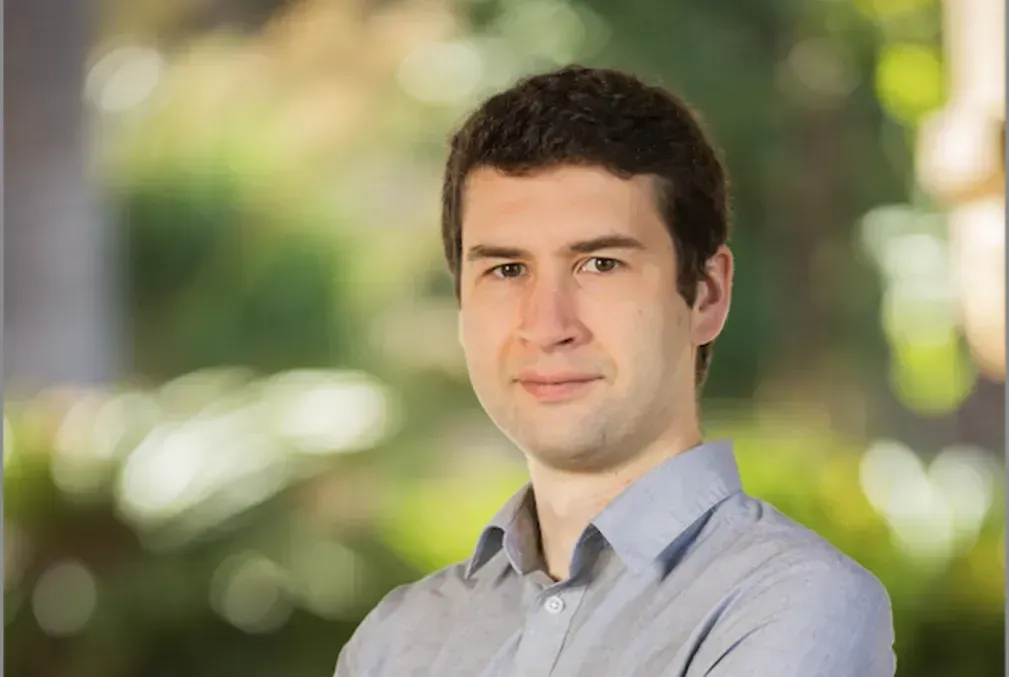

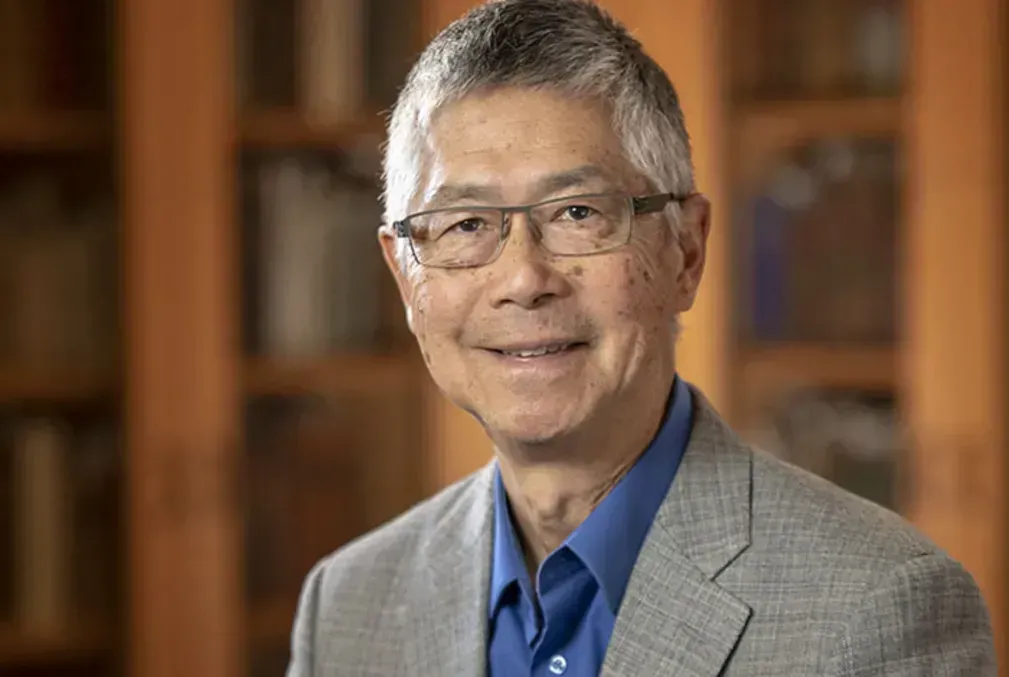

Vedika Khemani, associate professor of physics, was awarded the Infosys Prize 2024 in Physical Sciences, and Arun G. Chandrasekhar, professor of economics, has received the Infosys Prize 2024 in Economics. The annual prizes are given by the Infosys Science Foundation, a nonprofit founded by Infosys, an Indian multinational digital services and consulting corporation.

Revealing new phases of matter

Khemani earned the prize based on her research involving what are known as nonequilibrium quantum phases of matter. Being in “nonequilibrium” means these collections of matter are actively changing or being perturbed and, as a result, can often display novel, strange behaviors. Much of condensed matter physicists’ understanding of phases of matter, in contrast, is based on more settled equilibrium states, ranging from everyday solids and liquids to more exotic superconductors and plasmas.

By embracing the wilder, out-of-equilibrium side of condensed matter physics, Khemani is delivering new insights into the fragile quantum realm of matter at the smallest scales. Research in this realm has intensely focused on creating highly controllable quantum systems to further develop quantum computing. Besides offering the potential for revolutionary computing power, quantum computers also serve as fantastic new experiments for fundamental physics, giving researchers access to quantum matter in new regimes. The quantum algorithms that run on quantum computers are nonequilibrium quantum processes, so a better understanding of their novelty and complexity will advance computing and physics together.

“These experiments motivate us to ask: What new types of phases can we get in this context where the usual constraints of equilibrium thermodynamics just don't apply? What new regimes and possibilities are allowed?” Khemani said. “We want to find out.”

A prime example of such a dynamical, nonequilibrium quantum phase of matter is a time crystal, theoretically discovered by Khemani and colleagues in 2015 and experimentally realized in 2021 via a collaboration between Khemani’s group and the Google Quantum AI team. The crystals with which we’re all familiar, such as quartz or salt, display a repeating structure in space. Time crystals, by analogy, display a repeating structure in time, meaning that the material displays ever-changing patterns of order among its constituents, without any net input of energy.

By shining new light on novel phases of matter, Khemani’s research is opening paths toward more resilient quantum computation and other quantum information technologies.

The power of real-life social networks

Chandrasekhar received the award based on his insightful work regarding the impacts of social and economic networks in developing countries where formal institutions are typically weak. Much of his work has focused on villages in the southwest Indian state of Karnataka, which Chandrasekhar visited from time to time during summers he spent as a kid in the state capital of Bengaluru.

In his wide-ranging research, Chandrasekhar has studied how information and opinions spread thanks in large part to what might be called influencers—people who, by dint of reputation and social position, have significant, possibly indirect, reach throughout the entire village network.

“Some individuals have social power and are in a position where they can generate ‘virality,’ so to speak, when it comes to diffusing information,” Chandrasekhar said.

While studying this social learning, Chandrasekhar has innovatively used machine learning methods to map how informational units get transferred across thousands of households. A key finding has been that compared to costly formal campaigns, information can be disseminated cheaply if the right people are reached and sometimes more effectively when fewer people are initially reached as compared to using broadcasting technology. Chandrasekhar’s experiments have major policy implications, with real-world examples including promoting the uptake of vaccines, increasing financial inclusion via microfinancing, and combating rumors.

For Chandrasekhar, the research has proven to be deeply fulfilling, bringing together his lifelong passion for mathematics with his interest in understanding poverty issues in economically developing regions. “I’m not really an economist because I love economics,” he said. “I study economics because I want to study India and particularly the poor. Economics and math are just the means.”